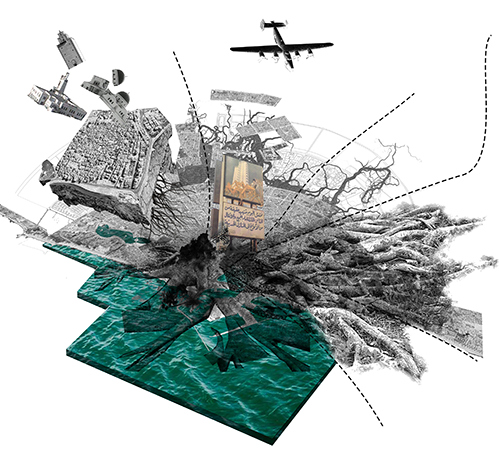

After the spark of the Libyan revolution in February 2011, a set of existential questions emerged in the Libyan cultural and political scene. It was an inquiry about “Libyanness” and how Libyans should represent their being in a new manner. However, there has been no coherent answer since then and, under the constant instabilities and civil conflicts that followed, it became relatively contradictory to form a collective unifying identity amidst the social and political chaos at play. This also manifested in the cultural realm and in the built environment. The very traditional concept of place ceased to be valid in the face of the contemporary challenges and disruptions that Libya has been going through. And akin to history teaching us that cities develop their own survival mechanisms as a reaction to the crises, the Libyan cities have also been generating their own in a series of critical situations. A state of being called placelessness. This article is an attempt to conceptualize and question the phenomenon of placelessness in the Libyan city of Benghazi, and investigate it beyond its supposed flat formal appearance to an urban socio-ideological level.

the project of identity throughout libyan history

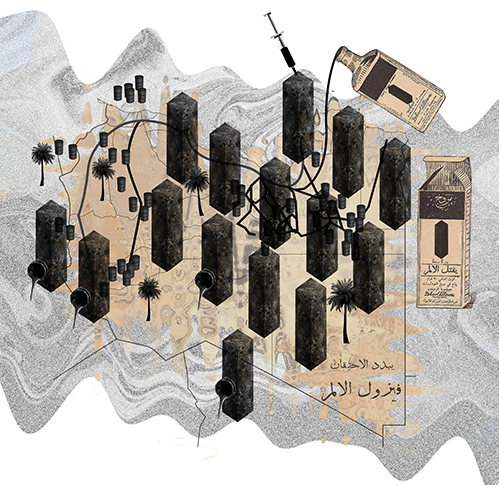

Libyan cities have undergone an intense flux of traumatic experiences since the 16th century: the Ottoman and Italian colonization, World War II bombing, Gadhafi’s totalitarianism and the civil wars. Such unrest has consequently produced persistent instabilities that are still affecting the social, cultural, and political fabrics of the country. Before the revolution of 2011, the project of forming a collective identity was an imposing socio-political ideology. Generally, the awareness of identity on a social level as a whole did not exist independent from class or political view but it was merely used as socio-political constructs of Nationalisms or Tribalism emphasized by power—be it in the Ottoman period, the Kingdom era of the Senussi, in the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, or even in the present, as the ongoing process to unify the image of Libyanness. All that could be partly interpreted as a consequence of the country’s long history of hegemonic and totalitarian regimes and its recent dependency on the rentier economy of oil revenues distribution and consumption, which has led the majority of Libyan citizens to be dependent on the state’s consumerist economy. This means that there has been no socio-economic independence and no chance to maintain a concept of local identity and independent uniqueness, neither on a social level nor on an economic level.

That leads to two crucial scenarios: one of radical openness to a global culture that diminished the importance of traditional identity and aesthetics; and the other of a nostalgia for a historical identity that was left behind from the Italian colonial modernist era onwards. The first is a transformative cultural force which falls into Deleuze’s concept of Deterritorialization1, an act of defamiliarization and a cultural displacement of the human subject (in this case the Libyans) from their preconceived traditional environment (the country’s territory). It means the prioritization of economic progress and the liberation from the bounds of traditional identity that was also manifested in Libya’s rapid urbanization and enormous expansion of cities. The second lies in the subjective and ideological realm, that is represented by a minority of Libyans—namely conservative intellectuals and organizations—who condemn globalization for the erasure of Libya’s local identity and tradition. This group rebukes the domination of flatscapes and calls for the conservation of historical value and aesthetics through the reconstruction of Libyan cities with historical references. The evolving tension imbued into those two scenarios reverberates spatially and culturally, constituting a state of placelessness.

benghazi: the placelessness of a city

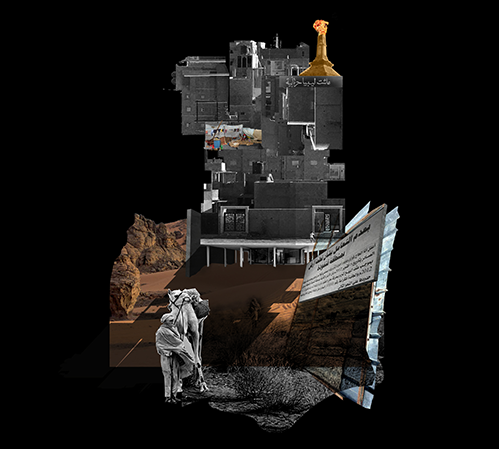

The city of Benghazi represents a strong example of placelessness. Benghazi’s city center has been a long standing symbol of local identity, holding a historical juxtaposition of cultures, mixing Libyan, Ottoman, Italian and Socialist architectural styles and narratives within its diverse urban fabric. During the civil war in 2014, the city was brutally bombed, affecting not only its central area but also several other residential neighborhoods. The destruction of the built environment was not only physical, but it also represented a metaphorical damage in Libya’s historical identity, engendering a state of collective grief in the whole country. Historical identity was turned into ashes and what remained was only a memory of it, a mental image suspended in a historical understanding of that. To cope with the bereavement, some people insisted on rebuilding the town exactly as it was, to revive its original character, to live in a state of nostalgia; while for the majority it meant an opportunity to start from scratch and build new identities, hopes and, possibly, a new value system.

The city’s ability to represent an authentic identity did not seem to be of any utility to Libyans, and the cultural project to rebuild historical identity became too expensive. The idea of reviving an identity that is prone to be destroyed again due to a conjuncture of uncertainties, seems like a psychological and economic burden that Libyans do not afford bearing. Thus, the convenient strategy was the production of new faceless identities, where and whenever possible; it is cheap and quick, and it does not require consensus, nor a historical base, its main strength being its unreadable mask of multiple references, sometimes modern, some other times postmodern, classical, Islamic, romantic, etc. Building everywhere and not following the state’s outdated city plans or planning policies, means constantly transgressing the definitions of homeland, becoming a mode of building that resists any conception of place as a whole.

As a place of non-identity, Benghazi can also be read as a place of resistance to identity and, consequently, rejecting any absolute definition. On being so, it paradoxically holds within its very placelessness a deconstruction of the traditional idea of place; and people start calling it a place only as a way of communicating a certain geographic or urban location defined by imaginary boundaries, though devoid of any traditional intrinsic values of being a place. Hence placelessness becomes a logical derivative out of the deterioration or absence of any coherent traditional meaning of place. This deconstruction has been viewed by the general cultural scene in Libya as a mischief and an unfortunate result of neglecting identity and traditional motifs. However, is this an intentional conscious decision that Libyans take? Or is it just an adaptive reaction to a constantly globalizing culture?

The instability of the Libyan political and economic conditions generated devastating chaos and trauma. It has shredded the country’s historical identity whilst producing a liberation from the need to maintain a certain identity. Such a procedure worked as a survival mechanism of urban contingency, that is manifested both in the urban and geographic scenes, as the phenomenon of placelessness, and in the unremitting spatial discontinuity present in different regions of Libya. In Benghazi, for example, this is noticeable in the contrast between the urban morphology of its traditional downtown, as aforementioned, and the emergent morphology of its peripheries.

This is a provocation to go beyond the pessimistic perception of placelessness, seeing it as an opportunity to rethink urban growth as an indeterminate procedure of survival by spatial means, a process that continues to function and to expand even in a severely dysfunctional system. It is a critical reflection proposing freedom through a detachment of the traditional concept of place that is tied to belonging, stability and connectedness.

The phenomenon of placelessness has been intensified in Benghazi with its growth and expansion during the social-politico-economic turbulences of the last decade. A good example is the residential district called Ganfotha, located on the western periphery of the city. It is one of the four districts that are considered as transgressing the official city plan which grants the status of informal to almost 80% of Benghazi’s built environment. Ganfotha is a self-generated and organized urban area, and a rootless piece of urban land dressed in what I call Grey Matter-s, a concrete mask that doesn’t seem to carry any symbolism or cultural meaning, this seemingly generic appearance drawing two crucial questions: is it a mask of anonymity evoking a camouflage to something that needs to be hidden within, an ideology, a character, or some values that could not be directly defined, accepted or understood? Or is this mask just a meaningless layer, which represents no features and no qualities, a free floating signifier?

the anonymity of placelessness

On one hand, if we read the anonymity of placelessness in Libya’s contemporary culture and aesthetics as a socio-ideological phenomenon that may indicate hidden meanings, we could conceive it as a sort of an urban Freudian slip2. Through this framework it is possible to make sense of the spatial and aesthetic informalities, or emergent non-traditional identities by considering the city as kind of a cultural patient or a subjectivity that is not always consciously responsible for its manifestations (slips) or its own masks. That means treating the act of building the city as a subconscious social behavior based on the correlations between these seemingly meaningless slips/masks and past events, trauma, or ideological discourses. On the other hand, if we assume that placelessness instrumentalizes the anonymous mask as a free floating signifier with no specific references or meaning, it would be to allow for all possibilities of references and meaning. As an example from outside the world of architecture and urbanism: in the 2008 film The Dark Knight3, the Joker character says “Give a man a mask and he will become his true self”. Anonymity here is understood as an instrument to break away from specificity and cultural implications. It reflects an open field of possibilities of what libyanness could mean and, for being so open, it could also mean that Libyan cities have never been able to reflect their authentic culture or ideologies through the aesthetics and values of a coherent traditional identity, but rather through this very cultural mask of placelessness, informality, and spatial transgression.

learning from placelessness

As Libyan or international architects and urbanists who are interested in studying the city of Benghazi, it is crucial to create awareness on the necessity to act as autonomous researchers who are not tied to any presumptions or ideological agenda. The city’s complex realities are manifested on its contingently grown environments, buildings, and people’s behavior. Placelessness is the inevitable present program of the city that is dominantly divergent from our old interpretation of what the city was in its traditional definitions. This present collective resistance to identity (be it unconscious or intentional), once meditated and deeply reinterpreted, could potentially influence future design decisions, allowing to reprogram the phenomenon of placelessness into a systematic urban and architectural knowledge. That could help in the project of post-war Benghazi reconstruction, as well as other Libyan cities, replacing the atavistic notions of reconstructing replicas of a shredded past, and non-valid historical identities.

While we have been spending too much dreamy efforts to actualize a better place deeply rooted in virtues and value, we neglected the critical importance to reinterpret and better understand the supposed nightmare that we are already living in. Placelessness… Although this might indicate a cynical attitude towards conceptualizing the Libyan built environment and its historical value, the general idea of this article is to propose new insights on the prioritization of different values and perspectives that we could also sympathize with.

مشروع الهوية عبر التاريخ الليبي

باتت تمر المدن الليبية بتدفق حاد من التجارب الصادمة منذ القرن السادس عشر: الغزو العثماني، والاستعمار الايطالي، تفجيرات الحرب العالمية الثانية، استبدادية حقبة القذافي، والحروب الاهلية التي عقبت. بالتالي انتجت هذه المحن اضطرابات مستمرة لاتزال تؤثر على النسيج الاجتماعي والثقافي والسياسي للبلاد. قبل ثورة ٢٠١١، كان مشروع تشكيل هوية جمعية اقرب الى ايدولوجيا اجتماعية سياسية مفروضة. بصفة عامة لم يوجد وعي ثقافي نحو الهوية على مستوى اجتماعي مستقل عن الجوانب الطبقية او السياسية، بل كانت محض بنائات سياسية اجتماعية من القوميات او القبائلية برزت بالسلطة، سواء كانت في الحقبة العثمانية، او مملكة السنوسية، في الجماهيرية الليبية، او حتى في الوقت الحاضر في العملية المستمرة لتوحيد الصورة الليبيانية ما بعد الثورة. كل هذا يمكن تفسيره جزئيا كنتيجة لتاريخ البلاد الطويل في سيادة النظم الشمولية والمهيمنة واعتمادها حديثا على اقتصادها الريعي في ايرادات النفط وتوزيعها و استهلاكها، مما ادى الى اعتماد الاغلبية العظمى من الليبيون على اقتصاد الدولة الاستهلاكي واهمال الاستقلال الاقتصادي الاجتماعي، وبالتالي تقليص الفرص في تكوين مفهوم عن الهوية المحلية على نطاق شعبي والتميزالمستقل سواء على الصعيد الاقتصادي او الاجتماعي كما ذكرنا.

أدى هذا إلى سيناريوهين حاسمين: أحدهما الانفتاح الجذري على ثقافة عالمية قللت من أهمية الهوية والجماليات التقليدية. والآخر هو الحنين إلى الهوية التاريخية التي تُركت للوراء منذ الحقبة الاستعمارية الإيطالية الحداثية وما بعدها. الأول هو قوة ثقافية تحويلية تندرج في مفهوم دولوز للانتزاع (Deterritorialization)1، وهي عملية التجرُّد من الألفة المكانية وتهجير ثقافي غير قهري للذات البشرية (في هذه الحالة الليبيين) من بيئتهم التقليدية المسبقة (أراضي الدولة). إنه يعني إعطاء الأولوية للتقدم الاقتصادي والتحرر من حدود الهوية التقليدية، والذي تجلى أيضاً في النمو السريع في البيئة الحضرية في ليبيا والتوسع الهائل للمدن. والثاني يكمن في المجال الذاتي والأيديولوجي، الذي يمثله أقلية من الليبيين – أي المثقفين والمنظمات المحافظة – الذين يدينون العولمة لمحو الهوية المحلية والتقاليد الليبية. تنتقد هذه المجموعة هيمنة اللاندسكيب السطحي (Flatscapes) وتدعو إلى الحفاظ على القيمة التاريخية والجمالية من خلال إعادة إعمار المدن الليبية بمراجع تاريخية. يتردد صدا هذا التوتر في هذين السيناريوهين مكانياً وثقافياً، مشكلاً حالة من اللامكان.

بنغازي: لامكان المدينة

تمثل مدينة بنغازي مثالاً قوياً على اللامكان. لطالما كان مركز مدينة بنغازي رمزاً عريقاً للهوية الحضرية المحلية، جامعاً بين الثقافات التاريخية، ومازجاً بين السرديات والأنماط المعمارية الليبية والعثمانية والإيطالية والاشتراكية ضمن نسيجها الحضري المتنوع. خلال الحرب الأهلية في عام ٢٠١٤، تعرضت المدينة للقصف بوحشية، مما أثر ليس فقط على مركزها ولكن أيضاً على العديد من الأحياء السكنية الأخرى. لم يكن دمار البيئة المبنية مادياً فحسب، بل كان أيضاً بمثابة دماراً رمزياً للهوية التاريخية لليبيا، وولد حالة من الأسي الجماعي في البلد بأكمله.

تحولت الهوية التاريخية إلى رماد وما بقي منها لم يكن سوى ذكرى لها، صورة ذهنية معلقة في فهم تاريخي لذلك. لمواجهة الفاجعة، أصر بعض الناس على إعادة بناء المدينة كما كانت تماماً، ولاعادة احياء طابعها الأصلي، والعيش في حالة من الحنين إلى الماضي؛ بينما كان يعني بالنسبة للأغلبية فرصة البدء من الصفر، لبناء هويات وآمال جديدة وربما منظومة قيمية جديدة.

لم يبدو أن قدرة المدينة على تمثيل هوية أصيلة ذات اي جدوى لليبيين، وأصبح المشروع الثقافي لإعادة بناء الهوية التاريخية مكلفاً للغاية، حيث فكرة إحياء هوية معرضة للتدمير مرة أخرى بسبب الظروف المتزعزعة تعتبرعبئاً نفسياً واقتصادياً لا يتحمله الليبيون. وهكذا كانت الإستراتيجية الملائمة هي إنتاج هويات جديدة مجهولة، حيثما وكلما أمكن ذلك، فهي رخيصة وسريعة، ولا تتطلب إجماعاً ولا أساساً تاريخياً، وقوتها الرئيسية هي قناعها متعدد المراجع غير القابل للقراءة، أحياناً تكون حداثية، و في بعض الأحيان ما بعد حداثية، كلاسيكية، او إسلامية، او رومانسية، إلخ.

البناء في كل مكان وعدم اتباع مخططات المدينة القديمة أو سياسات التخطيط للدولة، مما يعني التجاوز المستمر لتعريفات الارض والانتماء، ليصبح نمطاً للبناء يقاوم أي تصور للمكان ككل.

(كمكان) يفتقر للهوية، يمكن أيضاً قراءة بنغازي اليوم كمكان مقاوم للهوية، وبالتالي رفض أي تعريف مطلق لها. لكونها كذلك، فمن المفارقة أنها تحمل لامكانيتها في حد ذاتها، تفكيكًا للفكرة التقليدية للمكان؛ ويبدأ الناس في تسميته مكاناً فقط كطريقة للتواصل والدلالة على موقع جغرافي أو حضري بعينه محدد بحدود خيالية، على الرغم من خلوه من أي قيم جوهرية تقليدية تجعله مكاناً. ومن ثم فإن اللامكان يصبح مشتقاً منطقياً من تدهور أو غياب أي معنى تقليدي متماسك للمكان. اعتبر المشهد الثقافي العام في ليبيا هذا التفكيك بمثابة ضرر ونتيجة مؤسفة لإهمال الهوية والافكار التقليدية. ومع ذلك، هل هذا قرار واع متعمد يتخذه الليبيون؟ أم أنها مجرد رد فعل تكيفي نحو ثقافة متعولمة باستمرار؟

أدى عدم استقرار الأوضاع السياسية والاقتصادية الليبية إلى حدوث فوضى وصدمة مدمرة، عبرها مُزِقت الهوية التاريخية للبلاد، بينما في الوقت ذاته أنتجت تحرراً من الحاجة إلى الحفاظ على هوية معينة. ومثّل هذا الإجراء آلية بقاء للطوارئ الحضرية، والتي تتجلى في كل من المشاهد الحضرية والجغرافية، كظاهرة اللامكان، وفي الانقطاع المكاني المستمر الموجود في مناطق مختلفة من ليبيا. في بنغازي، على سبيل المثال، يمكن ملاحظة ذلك في التناقض بين التشكل الحضري لوسط المدينة التقليدي (البلاد)، كما ذكرنا سابقاً، والتشكل الناشئ لأطرافها.

يريد هذا الطرح ان يكون استفزاز لتجاوز التصور التشاؤمي لظاهرة اللامكان، كفرصة لإعادة التفكير في النمو الحضري باعتباره إجراء عشوائي للبقاء بالوسائل المكانية المتاحة، وهي عملية تستمر في العمل وتتوسع حتى في نظام وظيفي مختل بشدة. إنه انعكاس نقدي يقترح الحرية من خلال الانفصال عن المفهوم التقليدي للمكان المرتبط بالانتماء والاستقرار والترابط.

تمخضت ظاهرة اللامكان في بنغازي مع نموها وتوسعها خلال الاضطرابات الاجتماعية والسياسية والاقتصادية في العقد الماضي. ومن الأمثلة الواضحة على ذلك هو منطقة (قنفوذة)، الواقعة على الطرف الغربي من المدينة. وهي إحدى المناطق الأربع التي تعتبر مخالفة لمخطط المدينة الرسمي، مما يجعل ما يقارب ٨٠٪ من البيئة المبنية في بنغازي كأجزء حضرية غير رسمية. قنفوذة هي منطقة حضرية منظمة ذاتياً، قطعة أرض لا جذور لها ترتدي ما أسميه Gray Matter-s، قناع خرساني لا يبدو أنه يحمل أي رمزية أو معنى ثقافي معين، وهذا المظهر العام يوحي سؤالين مهمين: هل هو قناع مجهول الهوية يستحضر تمويهًا لشيء يجب إخفاءه بالداخل، أيديولوجية أو شخصية أو بعض القيم التي لا يمكن تحديدها أو قبولها أو فهمها بشكل مباشر؟ أم هل هذا القناع مجرد طبقة خارجية لا معنى لها، لا تمثل أي سمات ولا صفات، دال عائم؟

مجهولية اللامكان

من ناحية، إذا قرأنا مجهولية اللامكان في الثقافة والجماليات المعاصرة في ليبيا كظاهرة اجتماعية أيديولوجية قد تشير إلى معاني خفية، فيمكننا تصورها على أنها نوع من (الانزلاق الفرويدي)2الحضري. من خلال هذا الإطار، من الممكن فهم الجوانب العشوائيات الفراغية والجمالية، أو الهويات غير التقليدية الناشئة من خلال اعتبار المدينة كحالة مرضية ثقافية أو كذاتية لا تكون دائمًا مسؤولة بوعي عن ظواهرها (الزلات) أو اقنعتها الخاصة. وهذا يعني التعامل مع فعل بناء المدينة باعتباره سلوكاً اجتماعياً لا شعورياً قائماً على العلاقات المتبادلة بين هذه الزلات / الأقنعة التي تبدو بلا معنى والأحداث الماضية أو الصدمات أو الخطابات الأيديولوجية. من ناحية أخرى، إذا افترضنا أن اللامكان يوظف القناع المجهول للمدينة كدال عائم حر بدون مراجع أو معنى محدد ، فسيكون ذلك فتح لجميع احتمالات المراجع والمعاني. كمثال من خارج عالم العمارة والعمران: في فيلم The Dark Knight لعام 3٢٠٠٨، تقول شخصية الجوكر ” أعط الانسان قناعاً وسيصبح نفسه الحقيقية “، حيث تُفهم المجهولية هنا على أنها أداة للانفصال عن الخصوصية والآثار الثقافية. إنها تعكس مجالًا مفتوحاً من الاحتمالات لما يمكن أن تعنيه الليبيانية، وعبر هذا الانتفتاح الجذري، فقد تعني أيضاً أن المدن الليبية لم تكن أبداً قادرة على عكس ثقافتها أو أيديولوجياتها الأصيلة من خلال جماليات وقيم الهوية التقليدية المتماسكة، بل بالأحرى من خلال هذا القناع الثقافي المتمثل في عدم الاستقرار، وعدم الرسمية، والتعدي المكاني.

التعلم من اللامكان

كمعماريين وعمرانيين ليبيين أو دوليين مهتمين بدراسة مدينة بنغازي، من المهم خلق الوعي بضرورة العمل كباحثين مستقلين غير مرتبطين بأي افتراضات أو أجندة أيديولوجية. تتجلى الحقائق المعقدة للمدينة في البيئات والمباني وسلوك الناس. واللامكان هو البرنامج الحالي الحتمي للمدينة والذي يختلف بشكل كبير عن تفسيرنا القديم لما كانت عليه المدينة في تعريفاتها التقليدية. هذه المقاومة الجماعية الحالية للهوية (سواء كانت غير واعية أو مقصودة)، بمجرد تأملها وإعادة تفسيرها بعمق، يمكن أن تؤثر على قرارات التصميم المستقبلية، مما يسمح بإعادة برمجة ظاهرة اللامكان إلى معرفة حضرية ومعمارية منهجية، وبالتالي يمكن أن يساعد ذلك في مشروع إعادة إعمار بنغازي ما بعد الحرب، بالإضافة إلى مدن ليبية أخرى، لتحل محل المفاهيم الرجعية لإعادة بناء نسخ طبق الأصل من الماضي الممزق واعادة انتاج الهويات التاريخية منتهية الصالحية.

بينما كنا ننفق الكثير من الجهود الحالمة لتحقيق مكان أفضل متجذر بعمق في الفضائل والقيم، قد أهملنا أهيمة إعادة تفسير وفهم الكابوس المفترض الذي نعيشه بالفعل … على الرغم من أن هذا قد يشير إلى موقف ساخر تجاه تصور البيئة المبنية الليبية وقيمتها التاريخية، فإن الفكرة العامة لهذه المقالة هي اقتراح رؤى جديدة حول تحديد أولويات القيم و وجهات النظر المختلفة التي يمكن أن نتعاطف معها أيضاً في الشأن العمراني والثقافي.

footnotes + references

1/ Deleuze, G., Guattari, F., Foucault, M., Hurley, R., Seem, M. and Lane, H., 2012. Anti-Oedipus. London: Continuum.

2/ Freud, S., 1995. The psychopathology of everyday life. London: Hogarth Press.

3/ The Dark Knight. 2008. [film] Directed by C. Nolan. USA: Warner Bros., Legendary Entertainment, Syncopy, DC Comics.

Bokhsheem, N. (2015). Global values survey (comprehensive survey of Libyans views of values) (Research & Consulting Center University of Benghazi BRCC, Ed.). Research & Consulting Center University of Benghazi BRCC.

Deleuze, G., Guattari, F., Foucault, M., Hurley, R., Seem, M. and Lane, H., 2012. Anti-Oedipus. London: Continuum.

Elbabour, M. (2011). How geography and history enhanced unity in Libya. LibyaTV.

Freud, S., 1995. The psychopathology of everyday life. London: Hogarth Press.

Kezeiri, S. (1983). Urban Planning in Libya. Libyan Studies, 14, 9-15. doi:10.1017/S0263718900007767

Koolhaas, R., Mau, B. and for, O., 1995. Small, Medium, Large, Extra-large. Monacelli Press.

Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness. London: Pion.

The Dark Knight. 2008. [film] Directed by C. Nolan. USA: Warner Bros., Legendary Entertainment, Syncopy, DC Comics.

www.herzogdemeuron.com. (n.d.). HOW DO CITIES DIFFER? – HERZOG & DE MEURON. [online] Available at: https://www.herzogdemeuron.com/index/projects/writings/essays/how-do-cities-differ.html [Accessed 7 Apr. 2021].

author

Sarri is a 24 year old conceptual architect, artist, art curator, cultural activist, and the founder of TAJARROD Architecture and Art Foundation, based in Benghazi, Libya. His work is centered on an interdisciplinary synthesis between architecture, art, and the social sciences, dedicated to generating a critical understanding and attitude towards the built environment, and to investigating contemporary socio-cultural issues, identities and ideologies, and their impact on architecture and cities. His works manifest as: research, theoretical architectural projects, art curation, and collage art. He has published theoretical projects and essays online, and participated in several art exhibitions locally and abroad.

This article was developed as a part of his research at the TAJARROD Architecture and Art Foundation.

first published for projektado magazine issue 1: anonymity in design / may 2021