makeshift

—stories

—spontaneity

—episode 1 / TXTmob

—

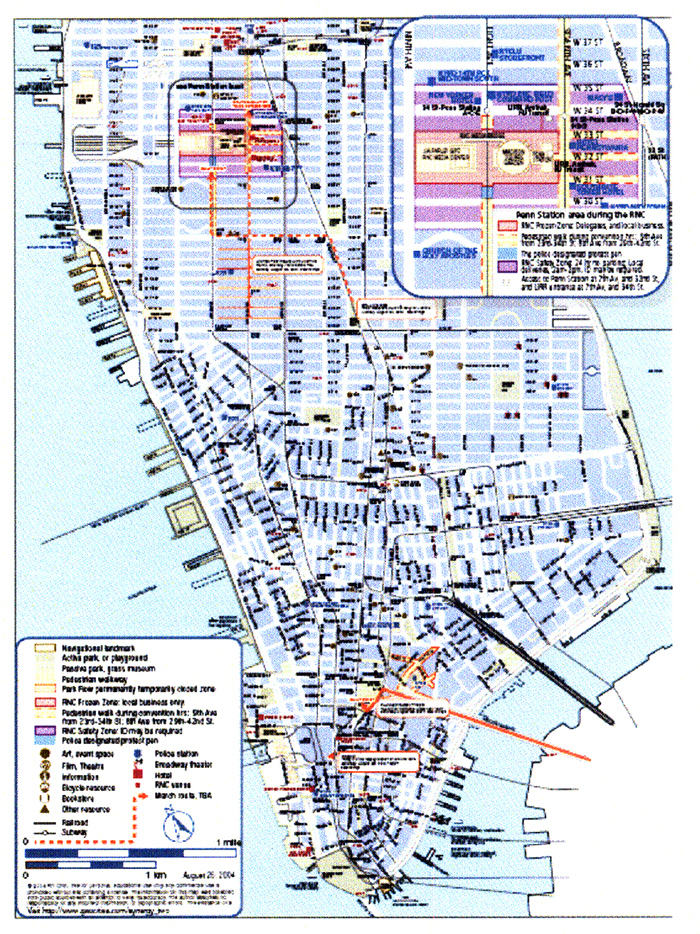

The National Convention protests of 2004 came at a time when law enforcement had become ever more efficient in cracking down on disruptive demonstrations through the militarisation of large areas around potential protest sites. To avert this opposition, as well as enable the participation of protestors with diverse backgrounds, affiliations and ideologies who were coming to voice their dissent, the organising coalitions, Bl(A)ck Tea Society in Boston and A31 in New York, adopted a radically decentralised model for the protests. On the one hand, decentralisation led to substituting one large assembly in a single area, with many demonstrations of smaller size all over Boston and New York City and throughout the days of the conventions. On the other hand, this approach meant that instead of a small group of organisers making most of the decisions, the coalition would provide support and communication infrastructure for a network of loosely affiliated, autonomous “affinity groups” who would plan and carry out the demonstrations.

2004 Republican National Convention Protest, New York City

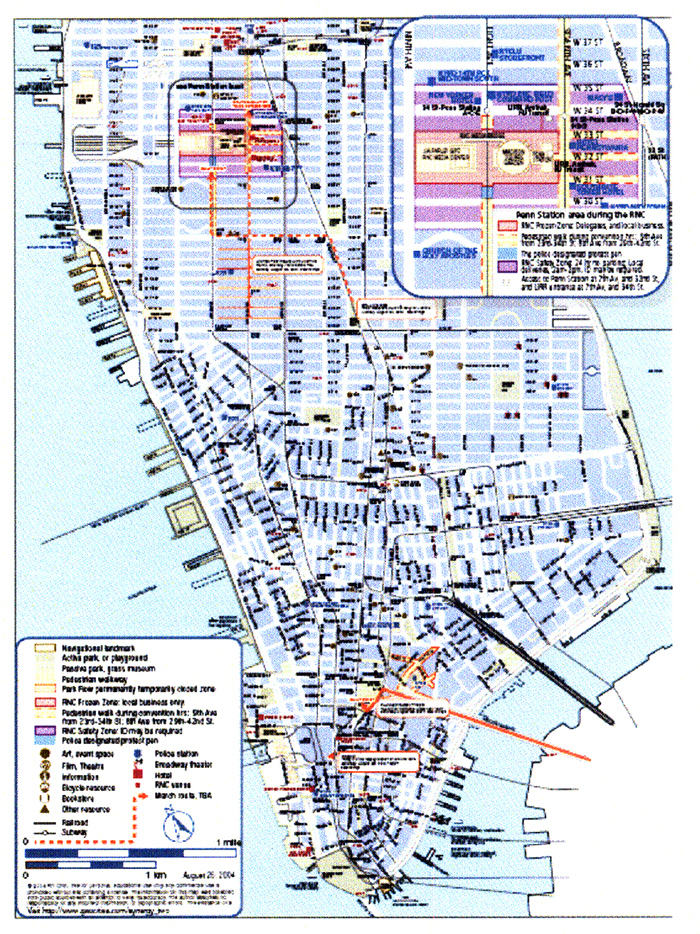

2004 Republican National Convention Protesters Map, New York City

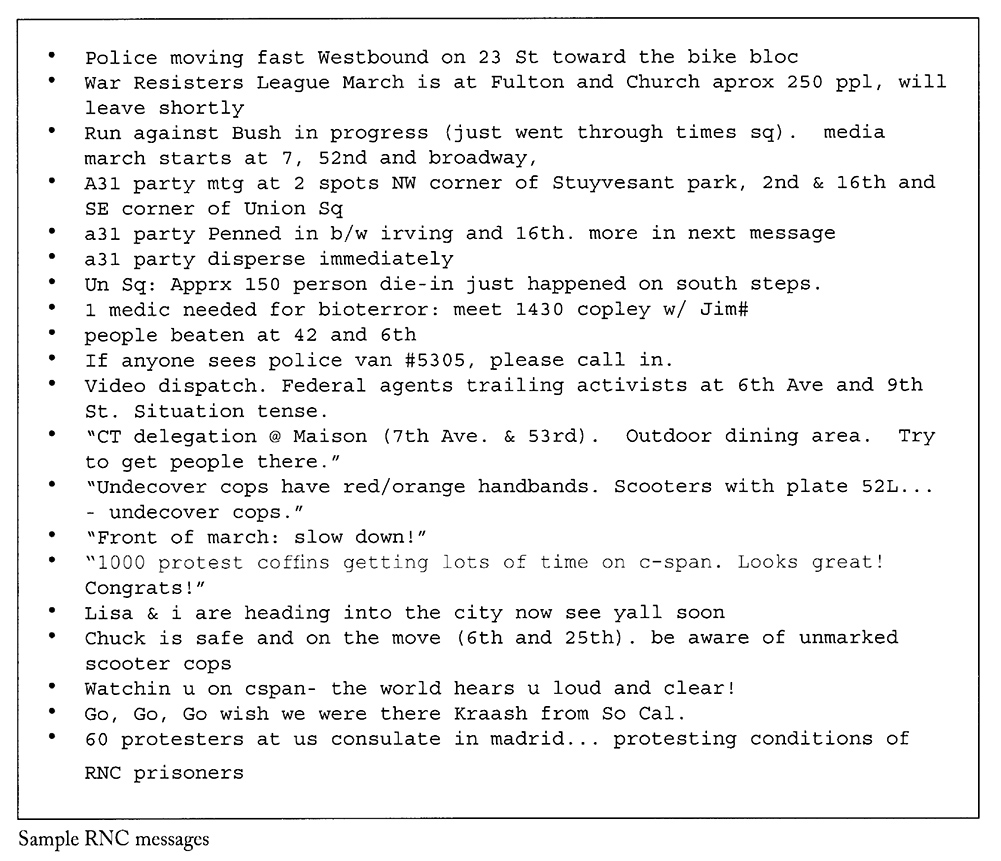

A combination of challenges, including communication among large numbers of people who didn’t know each other, the possibility of disruption by the police, the security of protesters during and after demonstrations, and a lack of resources, lead to the development of a new communication system based on SMS. Given that 2004 was before the widespread use of smartphones and social media platforms that today make instantaneous communication between large groups of strangers very easy, this system enabled people on the ground, equipped only with only a regular cell phone, to send and receive messages from different groups, as well as join new groups on the fly. These functions were carried out by the use of # and @ signs, pioneered by the hacker activist community at the time. The service used a little-known email-to-sms gateway, which meant the thousands of messages sent during the protest were free of charge.

TXTmob system diagram

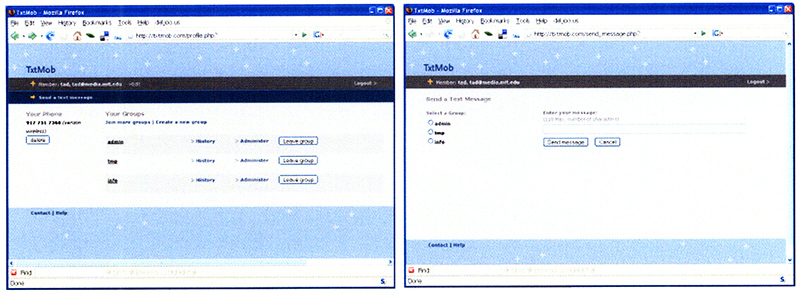

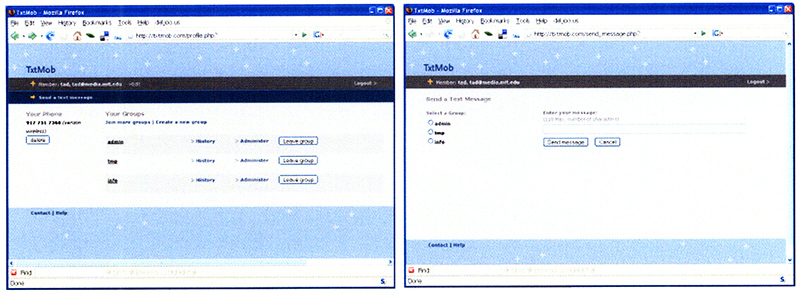

TXTmob web interface

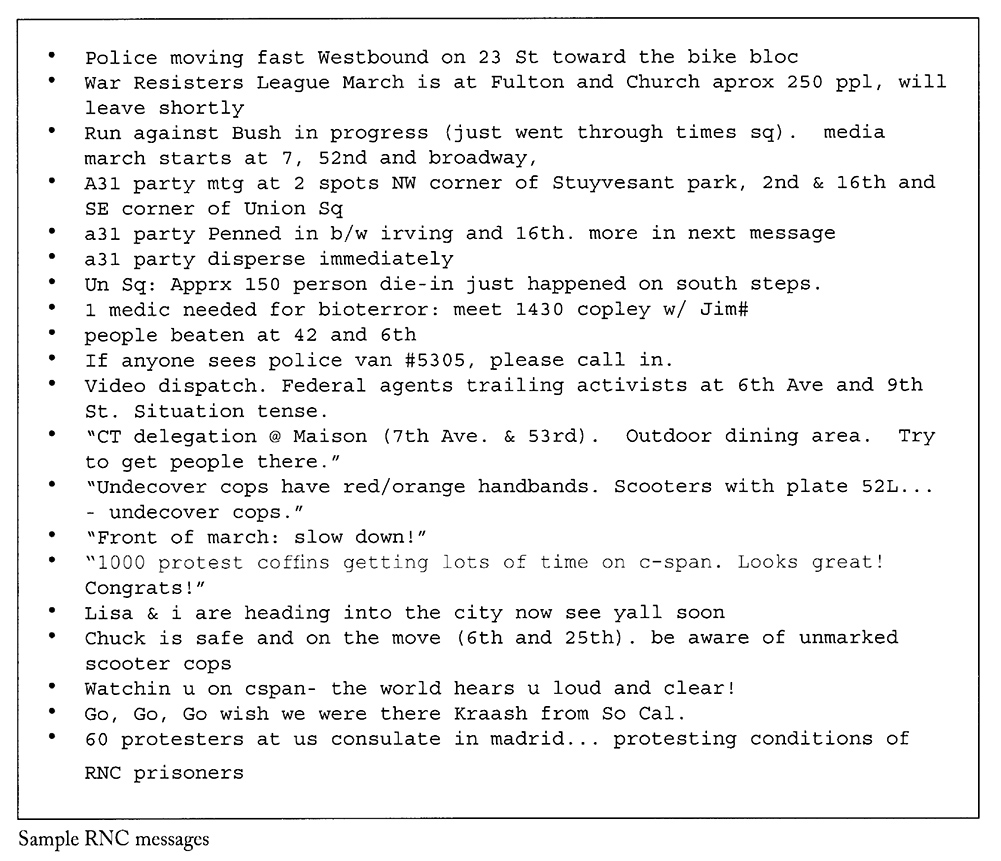

Example of messages send during the republican national convention in New York City

A more thorough account of the project has been documented by Tad in his PhD dissertation, Contestational design: innovation for political activism.

TXTmob was later made available as open-source, and was used in protests in other countries. Yet the broadest impact of the project can be seen in social media platforms today. Twitter, the micro-blogging platform, was born out of a podcasting startup called Odea. The group of hacker activists that participated in the development of TXTmob included members from Odea, who later, interested in the potential of the system, pitched the idea to their company. After weeks of using TXTmob and experimenting with it they decided to take it to scale and create what became Twitter.

2004 Ruckus Society SMS Summit in Oakland California, where members from Odea were present in discussing TXTmob

TXTmob and Twitter, Tad Hirsch, 2013

TXTmob is an excellent example of design activism that challenges many aspects of the narrative of mainstream commercial design: the collective and decentralised mode of creation that leads to radically different relationships; the personal motivation that fuels collaboration and enables addressing of pressing social issues; deeper ways of connecting to users that blurs the role distinction between designer and consumer.

The site of creation neither is nor has to be the market. It is precisely the creation that evades the rules and conditions imposed by the corporate world that can design new forms of social organisation we deeply need.

Learning from Activists: Lessons for Designers, Tad Hirsch, 2009

Bio:

Tad Hirsch is professor of Art & Design at the Northeastern University and currently works with Public Practice studio, employing design and engineering to issues of social justice. He has a long and interesting career as a professional, academic, and most importantly, as an activist.

first published for projektado magazine issue 2: survival and design / may 2022

episode 2 / cuban inventiveness

—

When discussing makeshift practices, and more specifically design practices that aren’t universally recognised as such because of their defiance of economic, legal, technological, material, and formal boundaries, the context of post-revolution Cuba provides an important and unique example of how such practices can become fundamental to the understanding of the material world.

In 1958, after years of armed revolt, Fidel Castro and his revolutionaries succeed in liberating Cuba from USA influences, overthrowing the corrupted government of Fulgencio Batista and establishing Cuba as the first communist country in the western hemisphere.

Suddenly Cuba, which was until the revolution a playground for the wealthy, full of casinos, nightclubs and increasingly US-controlled businesses and economies, became independent from US influences through a severance of diplomatic ties and the establishment of a trade embargo by president D. Eisenhower (which was then reenforced by president Kennedy after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961).

As Cuba finds in the Soviet Union their main trading partner after the revolution, the country begins to adapt to the use of Soviet products, technologies, parts, and practices, in a context in which the presence of US-based elements of material culture remains abundant.

The widely appreciated Aurika washing machine motor and an eletrical fan, images sourced from The Cuban Arts Group.

The necessity to make the most out of often incompatible resources, the economic hardship that accompanied the history of post-revolution Cuba, and the extensive implementation of national educational and literacy projects, created the perfect context for the widespread collective practice of informed and experimental makeshift activities.

This was reflected in the position of the government at the time, that explicitly encouraged Cubans to respond to the lack of resources through practices of self-production, reuse, repair, repurpose, and technical adaptation. A position captured by Ernesto Che Guevara’s quote from a 1961 speech: “Worker, build your own machinery”.

But while makeshift practices were already widely spread and promoted in the decades following the revolution in Cuba, the 1990’s imposed a new context and a new necessity for these activities.

In 1991, with the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba suddenly loses its main trade partner, 90% of its oil imports, and sees its GDP rapidly plummeting, as food shortages hit the island and major economic sectors, including agriculture, almost cease production due to the lack of oil and resources. This is the beginning of a period of incredibly restrictive and testing economic crisis, which was officially and misleadingly named by the Cuban government ‘el período especial en tiempos de paz’, the special period in the time of peace.

To many the ‘special period’ represents the crystalising moment for the Cuban makeshift approach, as the practical and educational experiences of the previous decades, combined with an incrementally severe economical and political crisis, lead to increasingly impactful and innovative forms of adaptation and design.

Evidence of this collective and widely spread approach to makeshifting is not only present in the material and social culture of Cuba today, but was also documented in publications and books. Two of which, published in the early 90’s, aimed to consolidate and share the practical knowledge Cubans had of life in a moment of shared struggle.

In 1991 Verde Olivo, a Cuban military publishing house, released ‘El libro de la familia’, the book of the family.

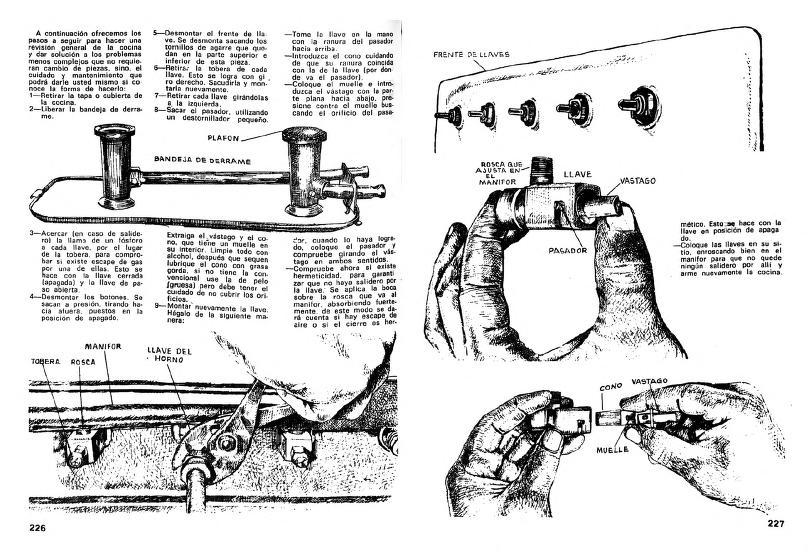

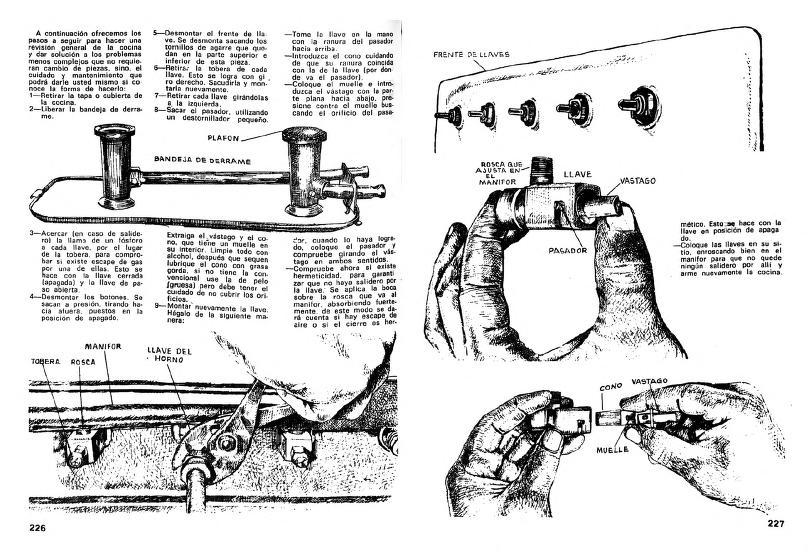

Page 226 of ‘El libro de la familia’, 1991.

This book, developed and distributed in collaboration with the Cuban armed forces and the Federation of Cuban Women, represents the awareness the government had of a very severe economic crisis, and an attempt to utilise knowledge to reshape consumption and production patterns within the island.

The book itself is a comprehensive manual collecting the knowledge already present within the Cuban army or taken from other popular publications, and it is addressed to the general population, providing solutions to the common problems that that moment was imposing on the people.

The book spans from information on soil composition, to acupressure, to appliance repair.

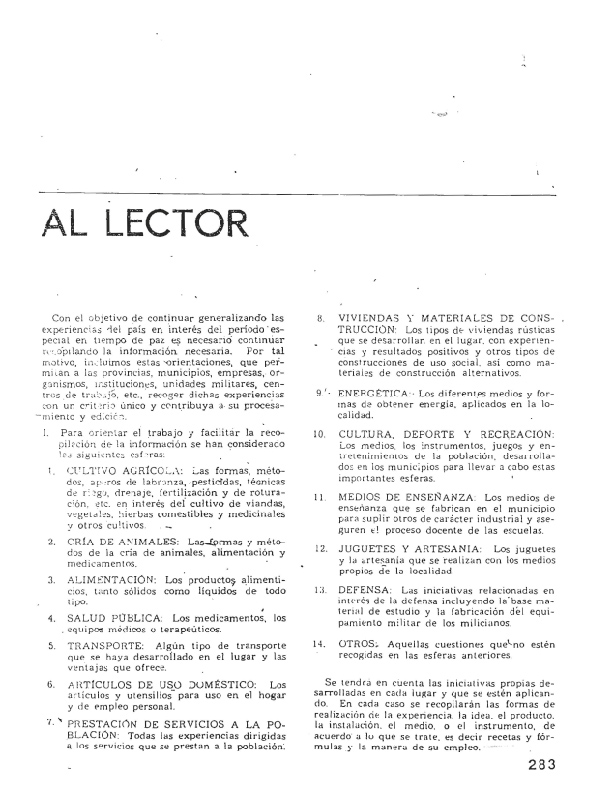

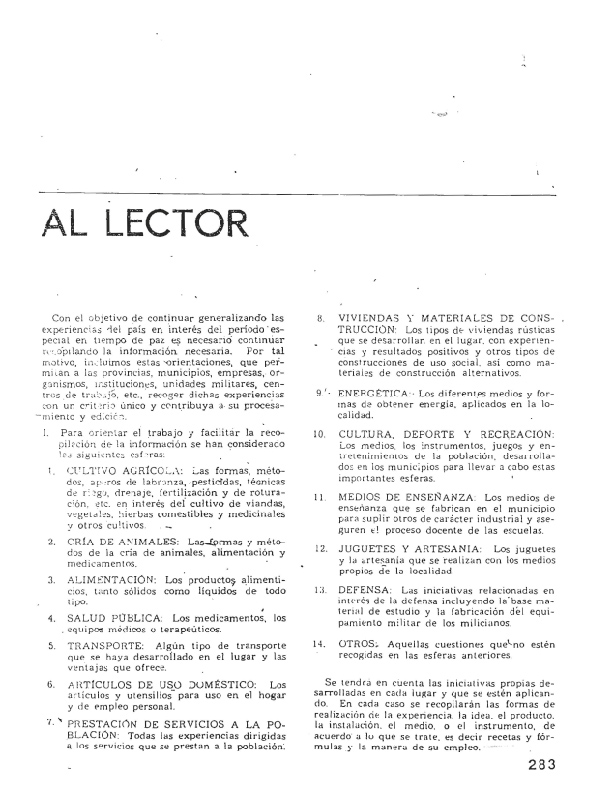

Less than two years later, a new book was published extending the scope and reach of the first one, titled ‘Con nuestros propios esfuerzos’, with our own efforts.

The radical change that this book presents is one of format, content, and intent. While the previous book conformed to a more institutional style of manual, with contents mostly attributed to authoritative sources and then provided to the population, here the people become the main source of information and knowledge, the knowledge of the people for the people of Cuba.

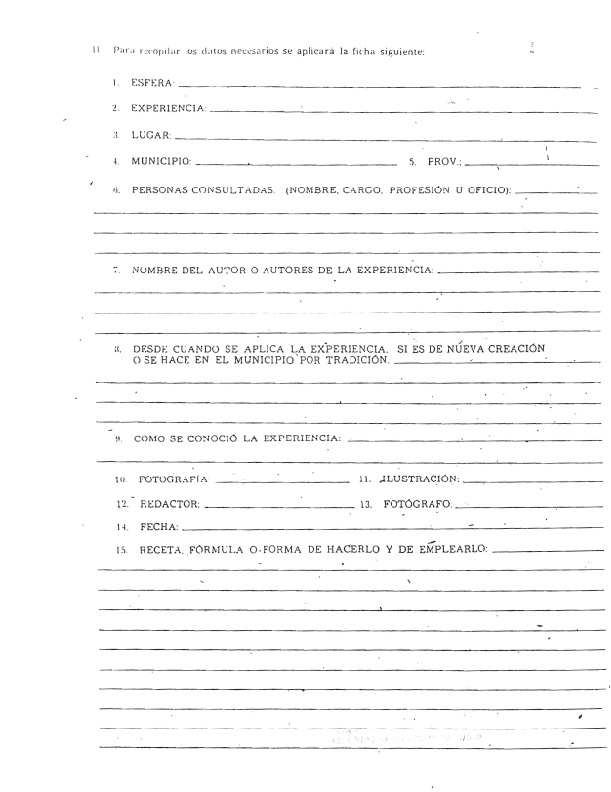

Submission form found in the last pages of ‘Con nuestros propios esfuerzos’, 1992.

The book is a collection of experiences recorded throughout the island, stories of improvisation and solutions.

In different municipalities, people could hand in a record of their experiences in an attempt to make knowledge available to all and help each other in a dissemination project that supported the atmosphere of social solidarity present in the island at the time. What is featured in this book maintains the instructional and utilitarian language of a manual, but represents a much broader shared dialogue. From the use of soviet componentry to create new production machinery, to food recipes, from energy consumption to children’s toys. The book is truly vast in its scope and themes.

Today, both books remain as a significant source of information on the makeshift practices of the Special period, and even to those who weren’t there during that time, still provide a form of representation of a mentality of which legacy can still be observed today.

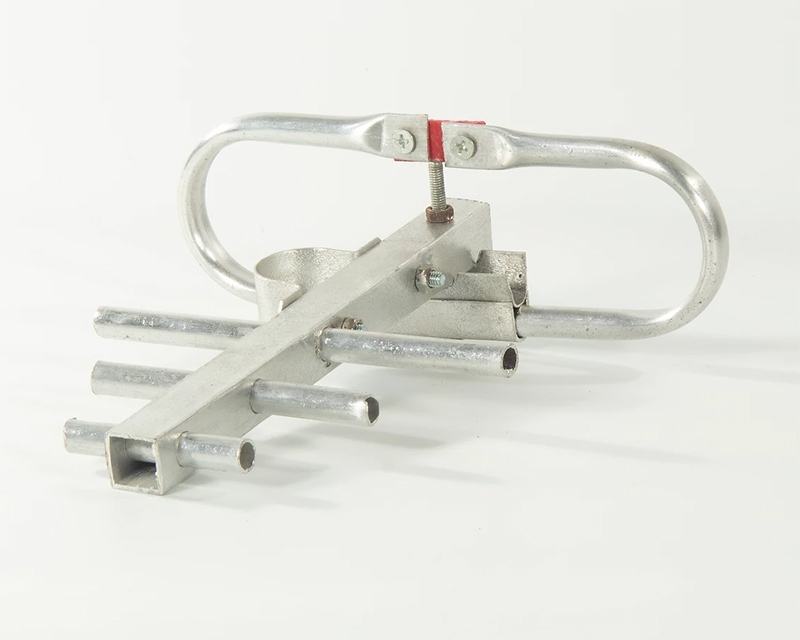

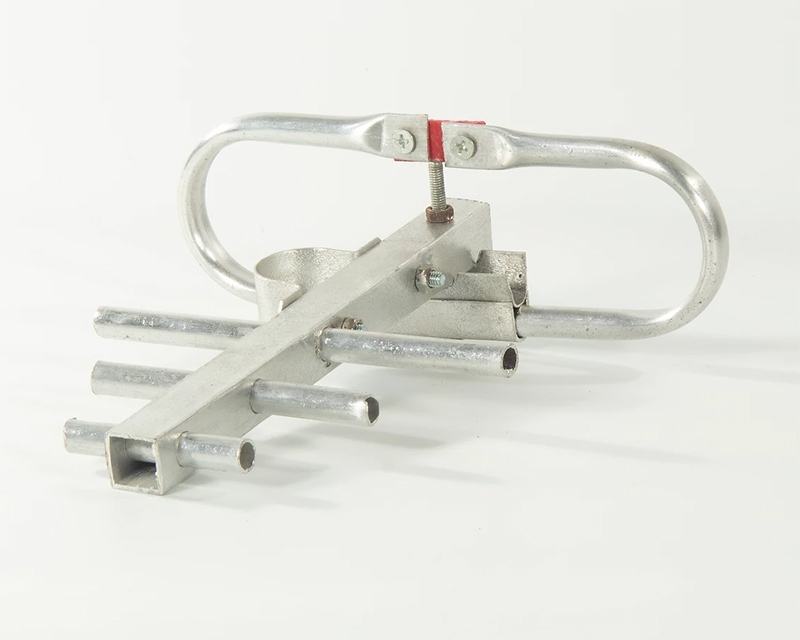

Bicycle attachment for knife sharpening, photo by Nicoló Lanfranchi.

Anything from healthcare to food preparation, was in some way shaped by the economic and political context of that decade. And even though the special period officially concludes in the year 2000, the behaviours and approaches that it formed extend well past that moment and start to respond to different problems, with a large number of clear examples still defining the following decades. As permanent pieces of heritage ingrained in local culture.

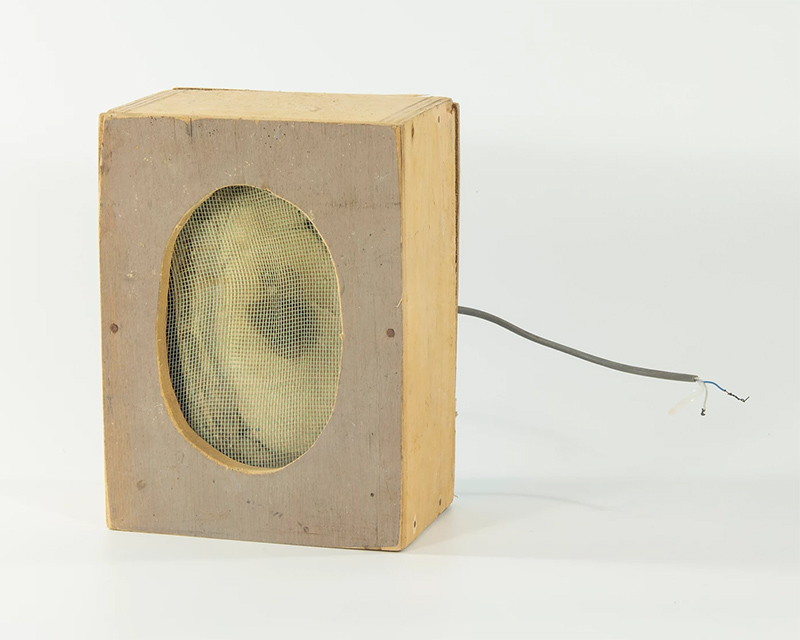

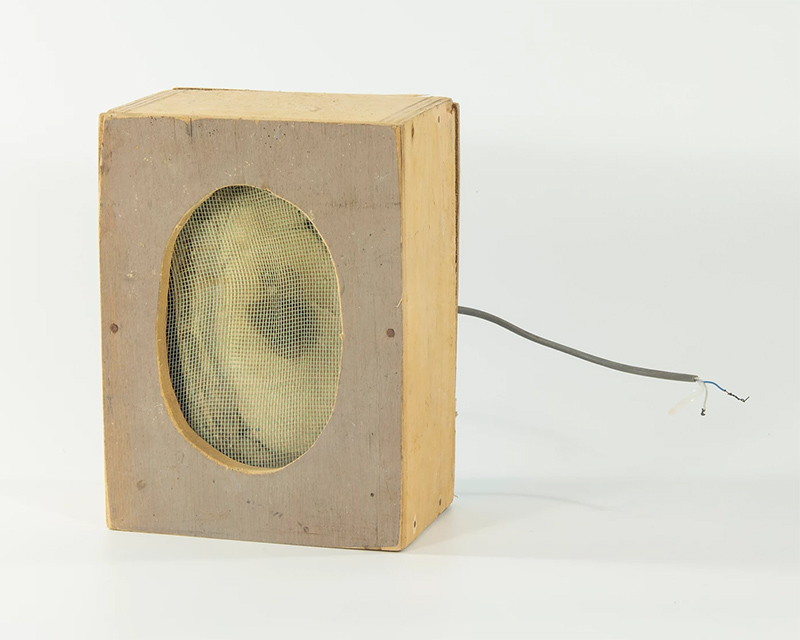

Makeshift antenna and audio speaker, images sourced from The Cuban Arts Group.

We see this in the era of digitalisation and globalised communication, as Cuban resourcefulness starts to play a more and more active role in the digital and virtual spaces. The severely limited opportunities to access international dialogue, and ultimately the general lack of internet as a means of communication and content sharing, presented new challenges and opportunities for collective problem solving. Ultimately resulting in the establishment of locally based alternatives to the internet, and alternative ways of sharing digital content.

Overall, the complexity of the Cuban experience over the last 60 years can be interpreted and discussed through countless different lenses, narratives, analytical processes, and comparisons. And even though retrospectively and comparatively many of the makeshift practices that can be observed in Cuba’s history carry a strong political and social message, it is unclear how much they were considered as such by those experiencing them.

But besides the different perspectives and interpretations of this context, Cuba provides important insights into systems in which the individualistic tendencies of wealthier economies haven’t been as impactful, and leaves space to imagine what can be achieved when collective action and solidarity are fundamental elements of reality.

Is there a form of liberation that comes from the ability to interact at this level with the material environment? Is challenging the limits of formal, technological, economic, and legal boundaries innovation, disobedience, or both?

Learn more about it by listening to our podcast episode: Cuban inventiveness.

Bios:

César Beuve-Méry is currently working as a UX Designer/Researcher in a Parisian design agency. He lived in Havana, Cuba from 2006 to 2012. He finds a strong interest in the less formalised aspects of design, notably those objects and/or spaces that derive from intuition and immediate need.

Follow his Instagram page : @everydaydesigners

Joe Purvis is currently working as a researcher investigating online harms. He previously worked sourcing art for a private Cuban art collection. He completed a BA in History with a focus on the politicisation of race in post-Revolutionary Cuba. He also holds an MA in Conflict Resolution in Divided Societies with a focus on the study of social movements. He lived in Havana, Cuba from 2000 to 2012. He is interested in the relationships between power structures and the lived experiences of individuals.

first published for projektado magazine issue 2: survival and design / june 2022

episode 3 / zines & self-publishing

—

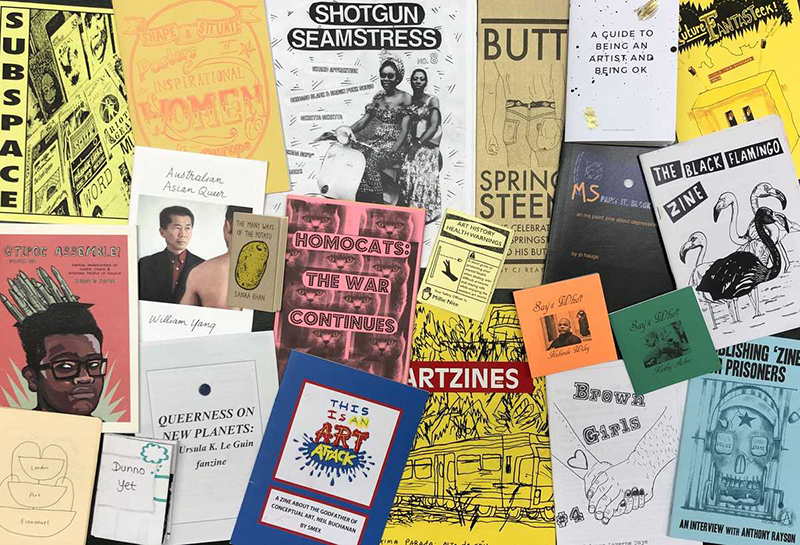

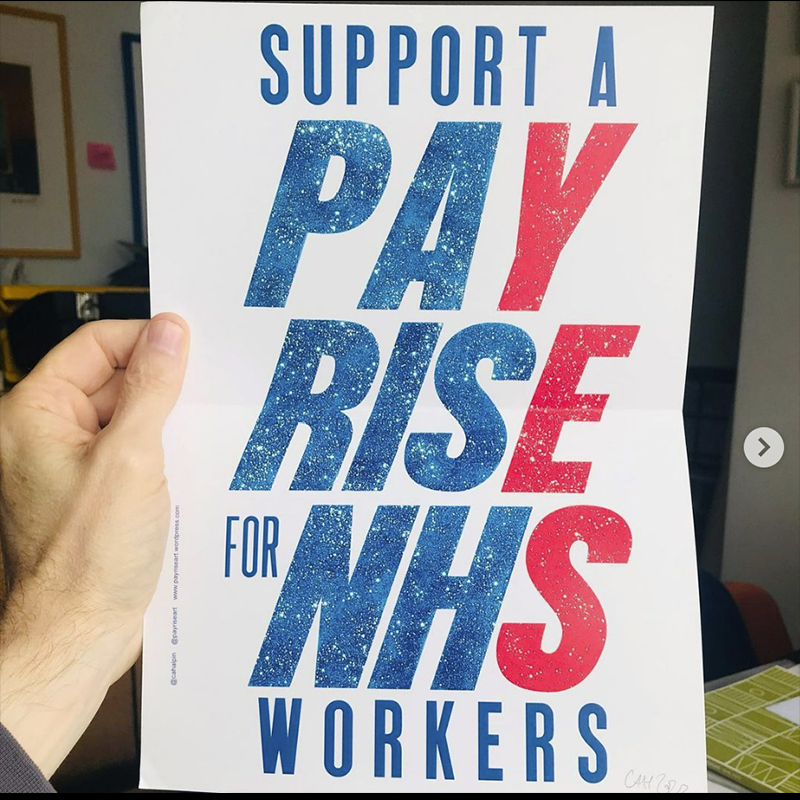

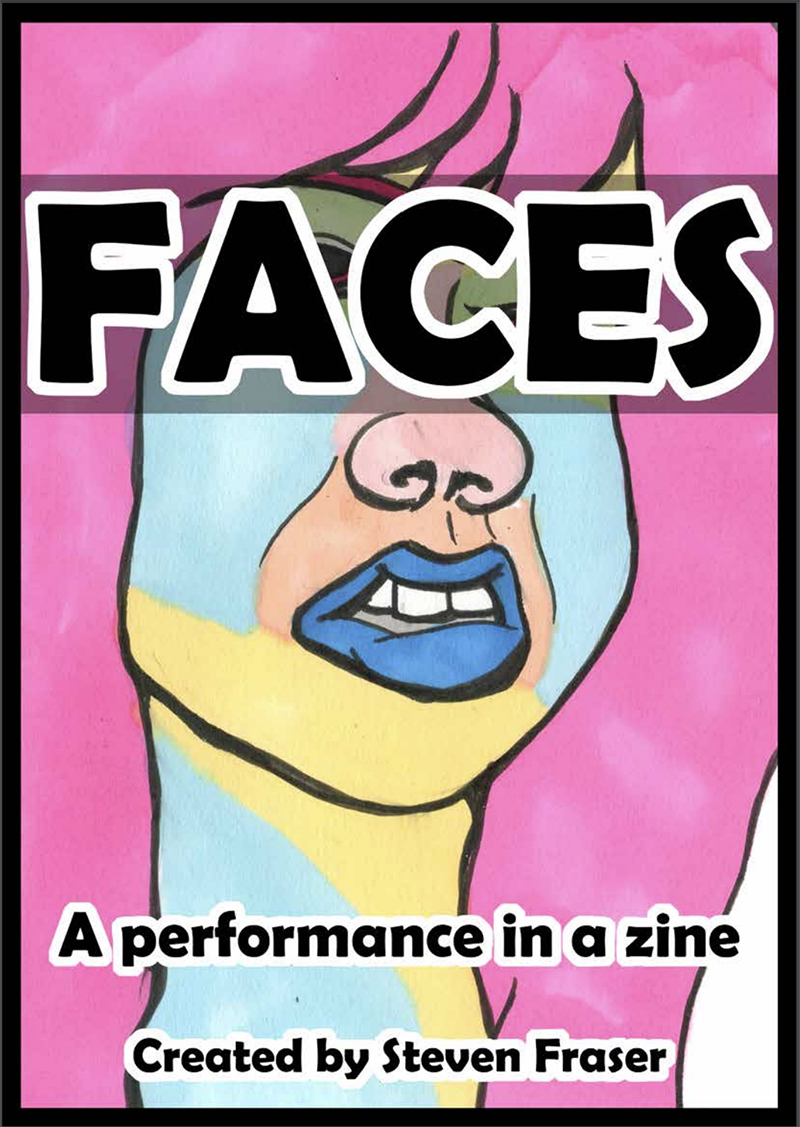

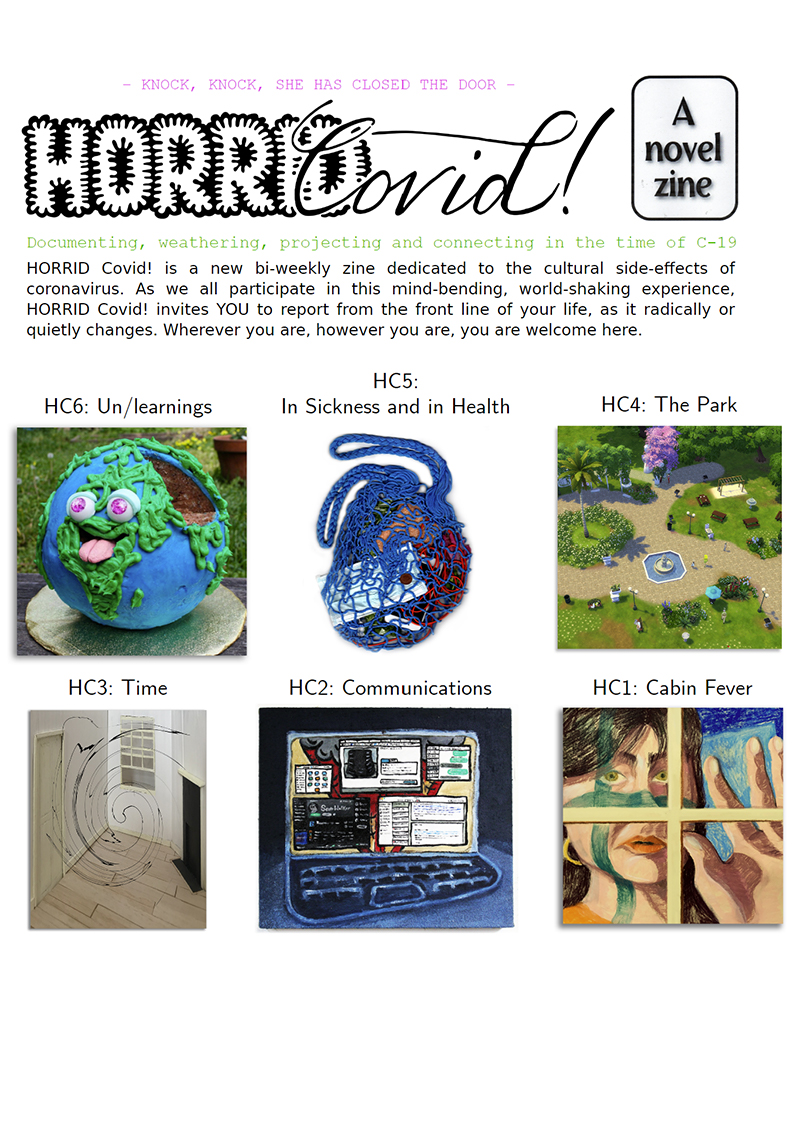

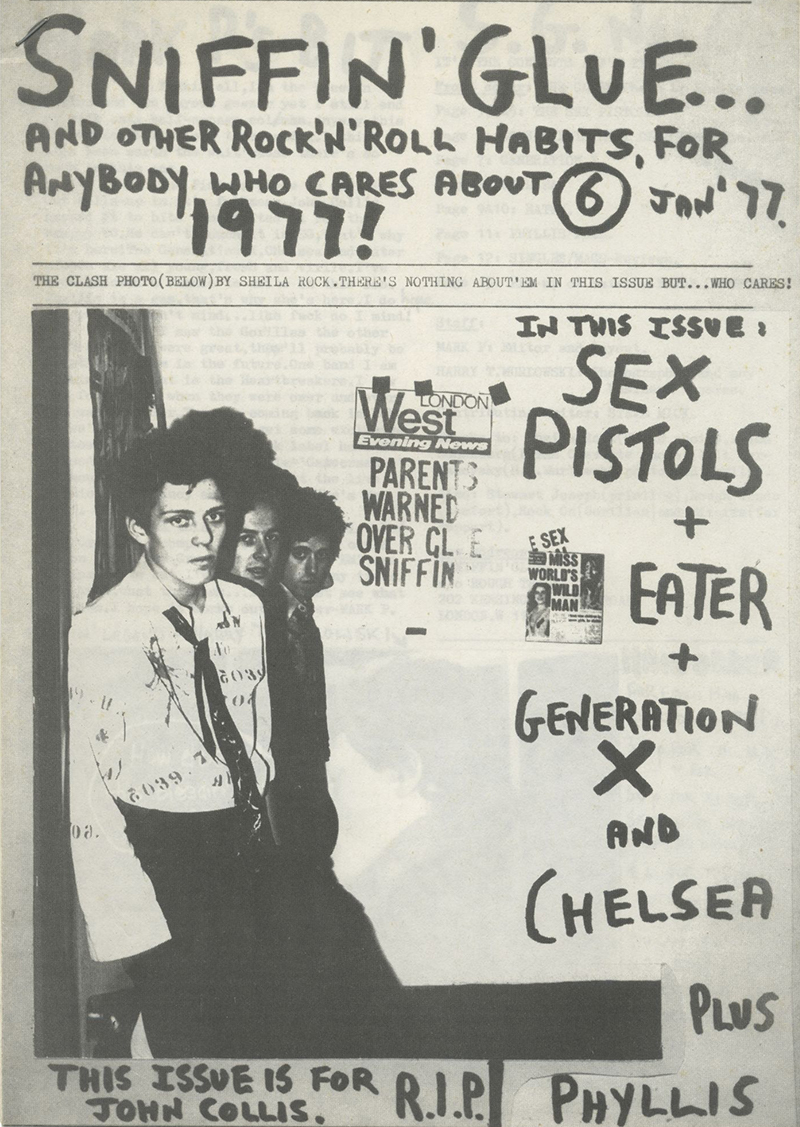

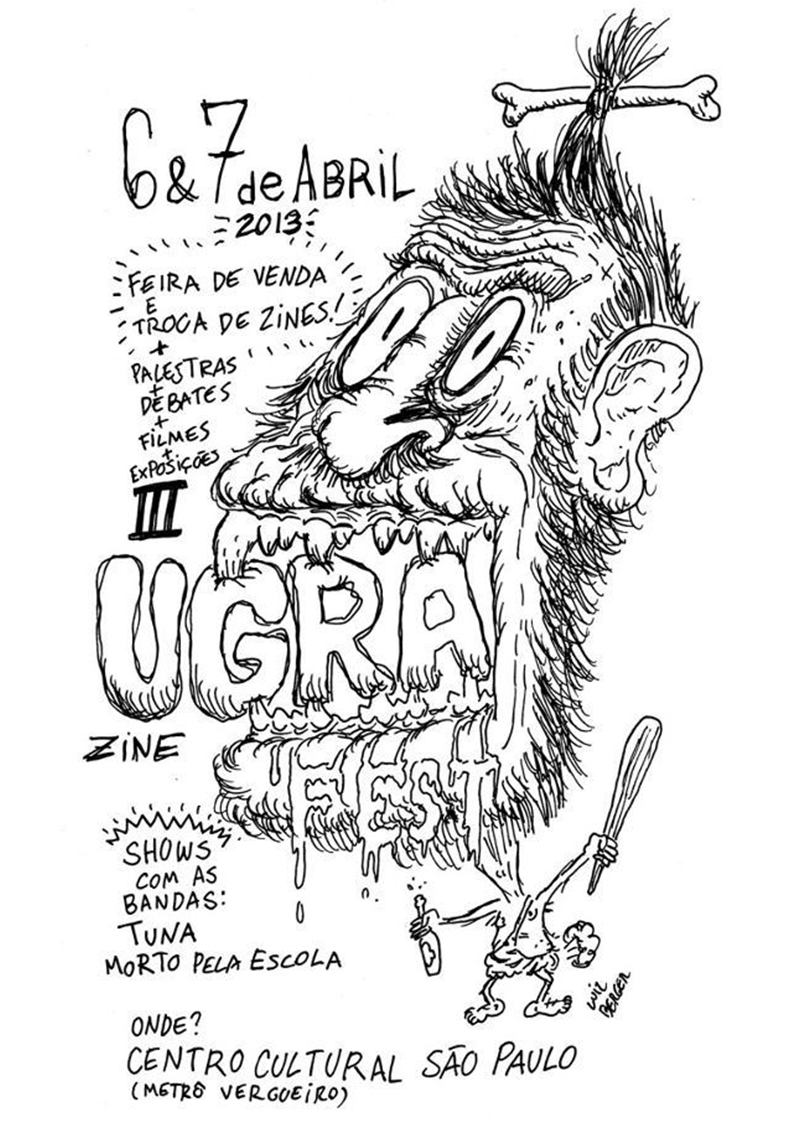

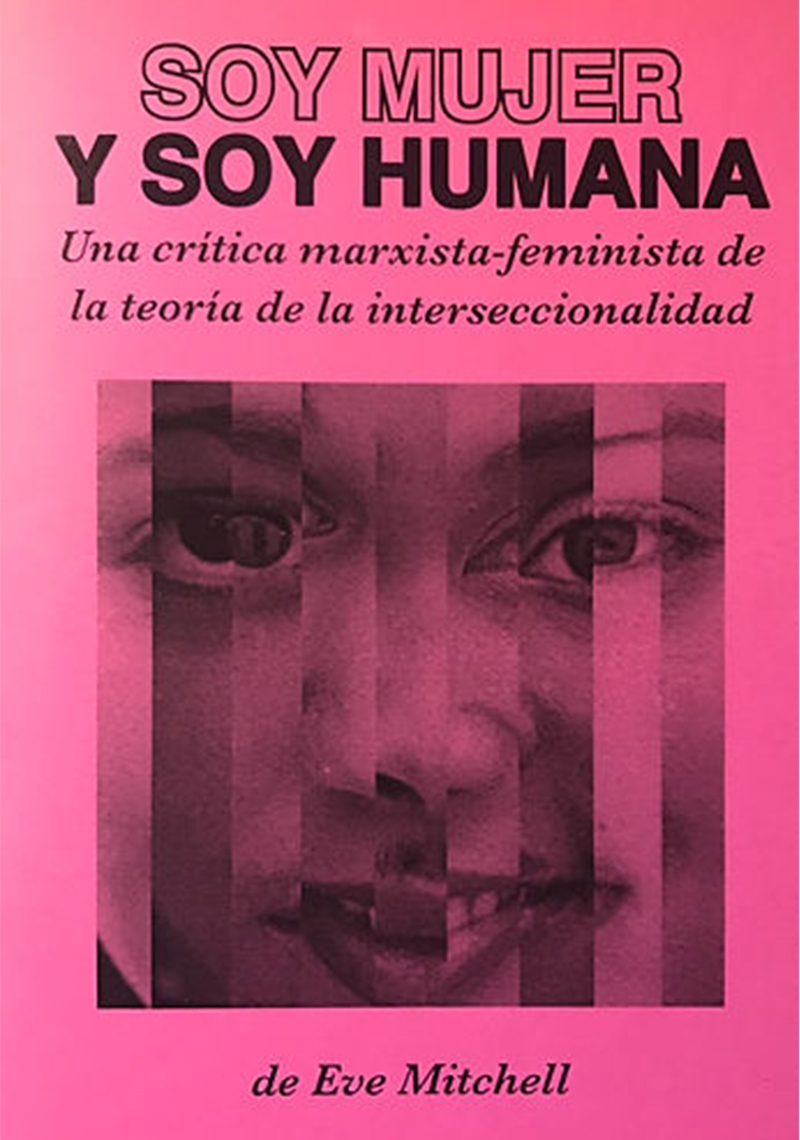

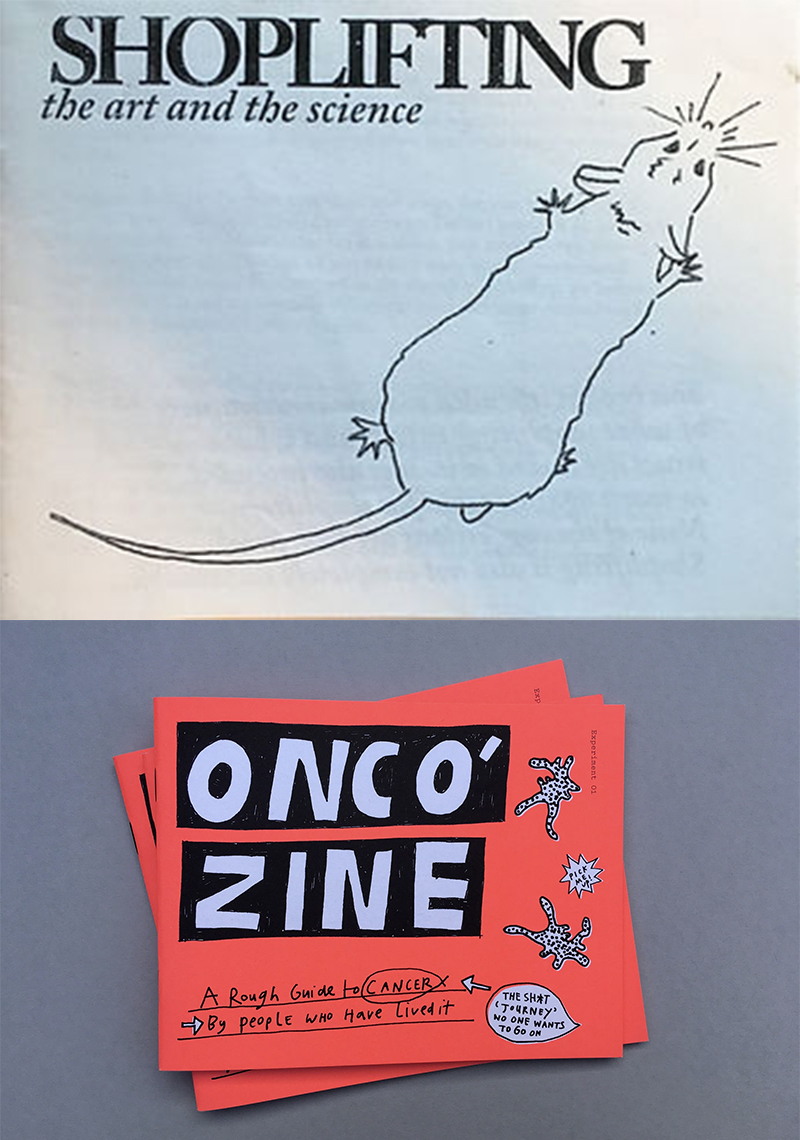

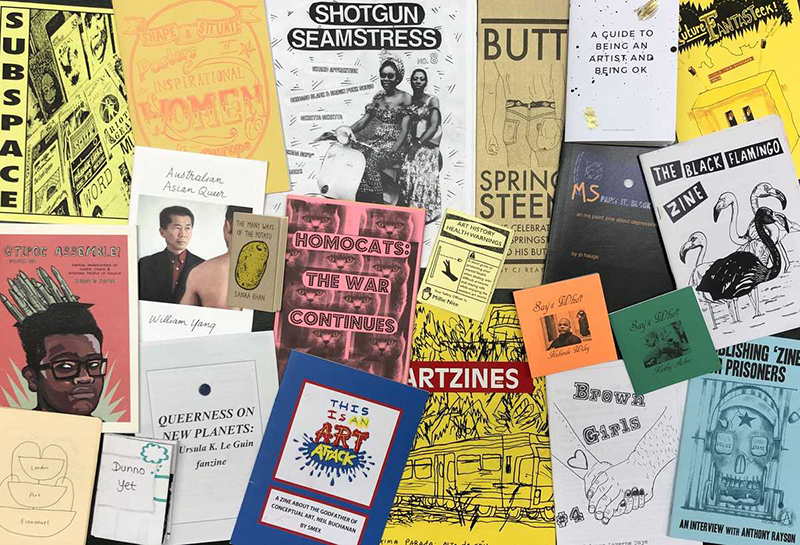

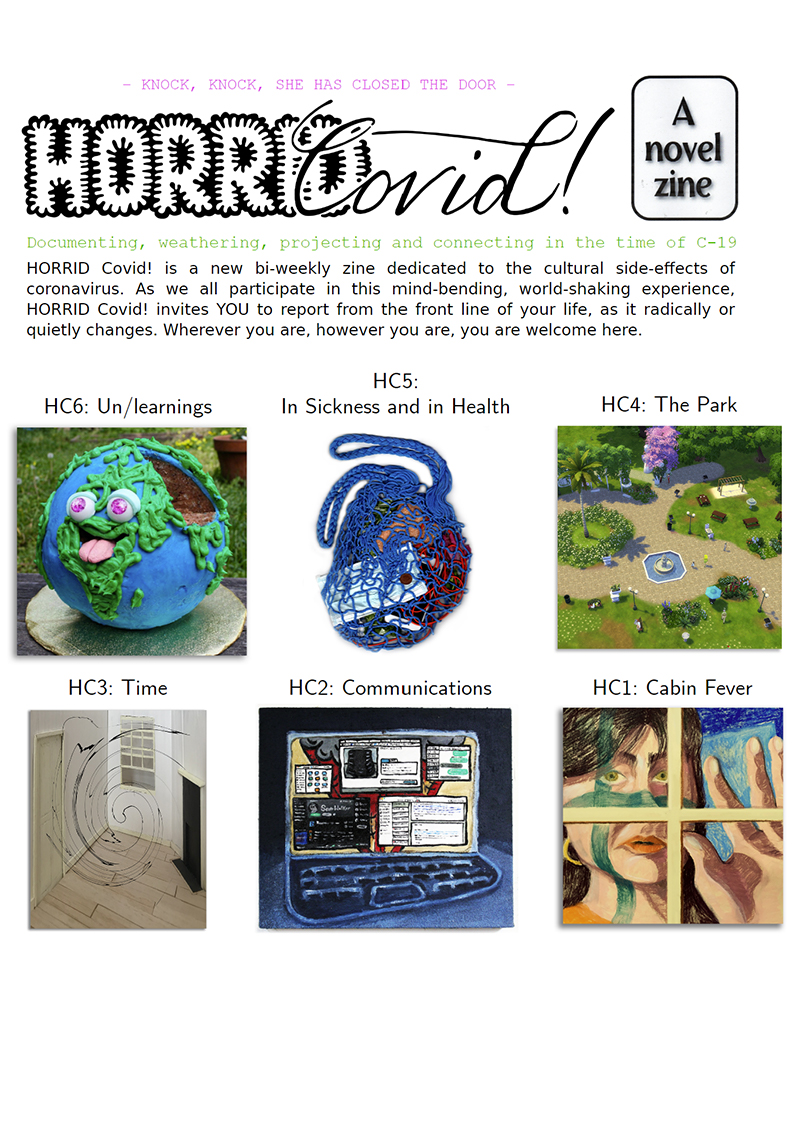

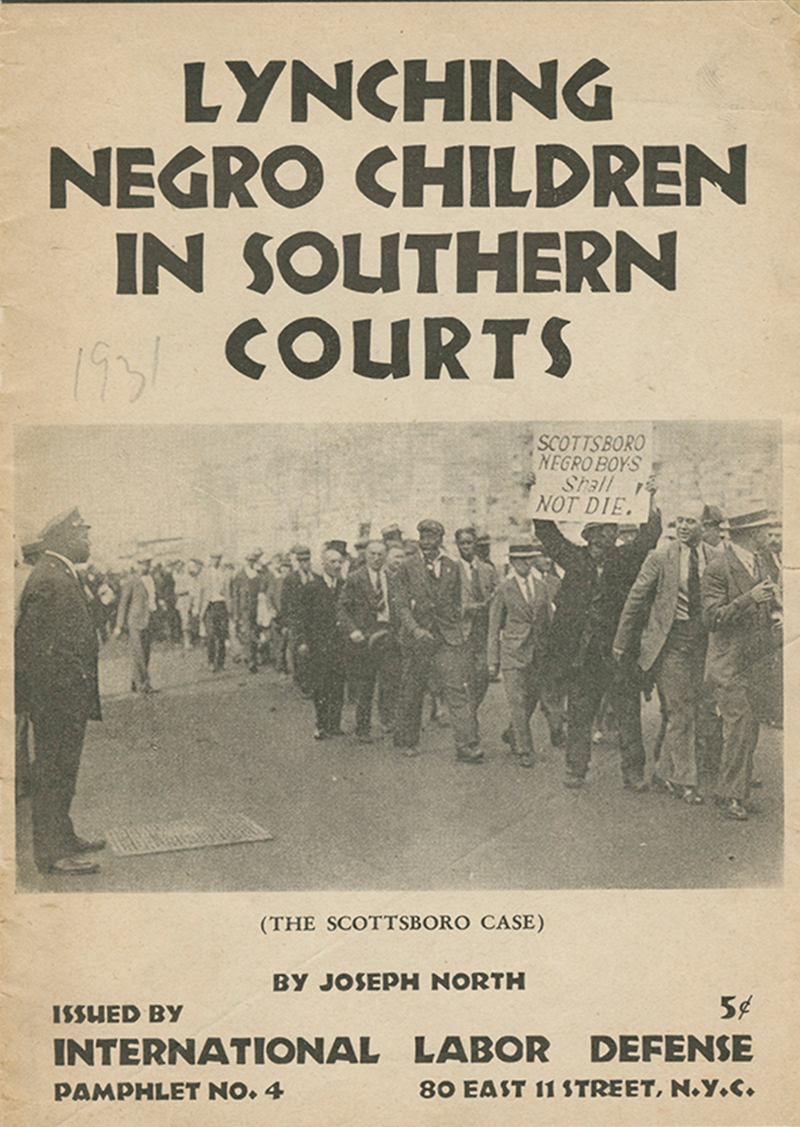

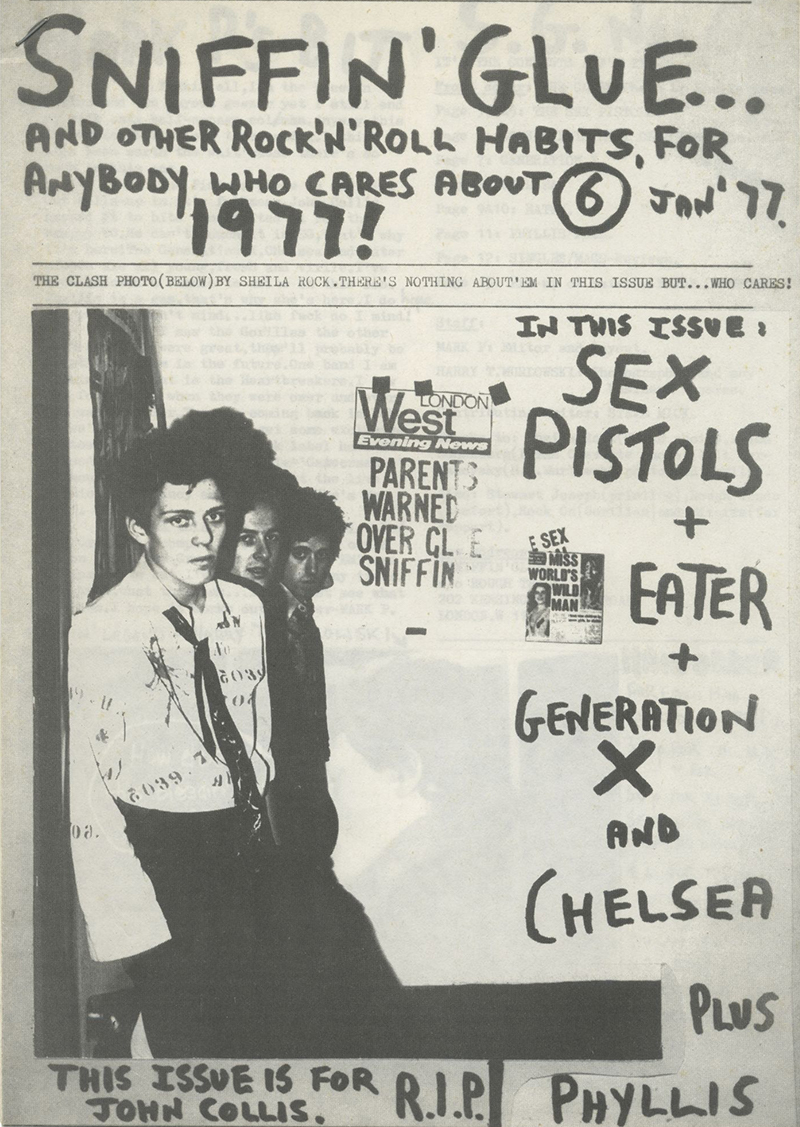

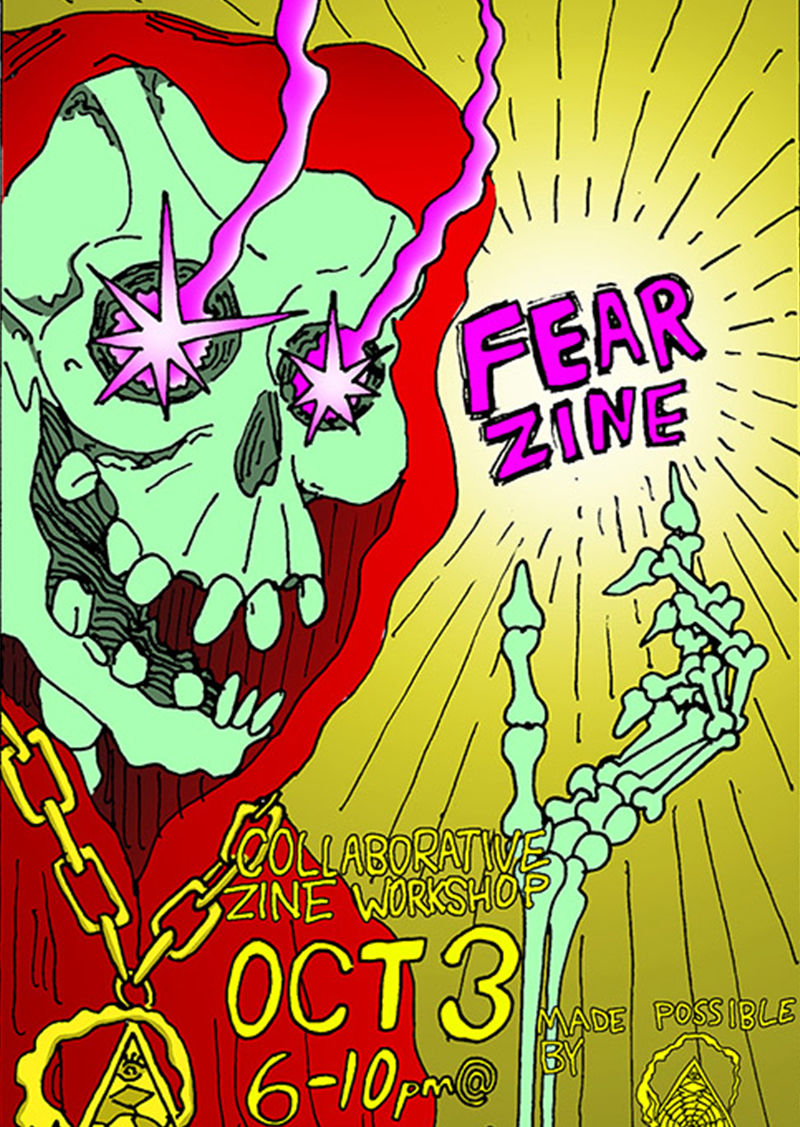

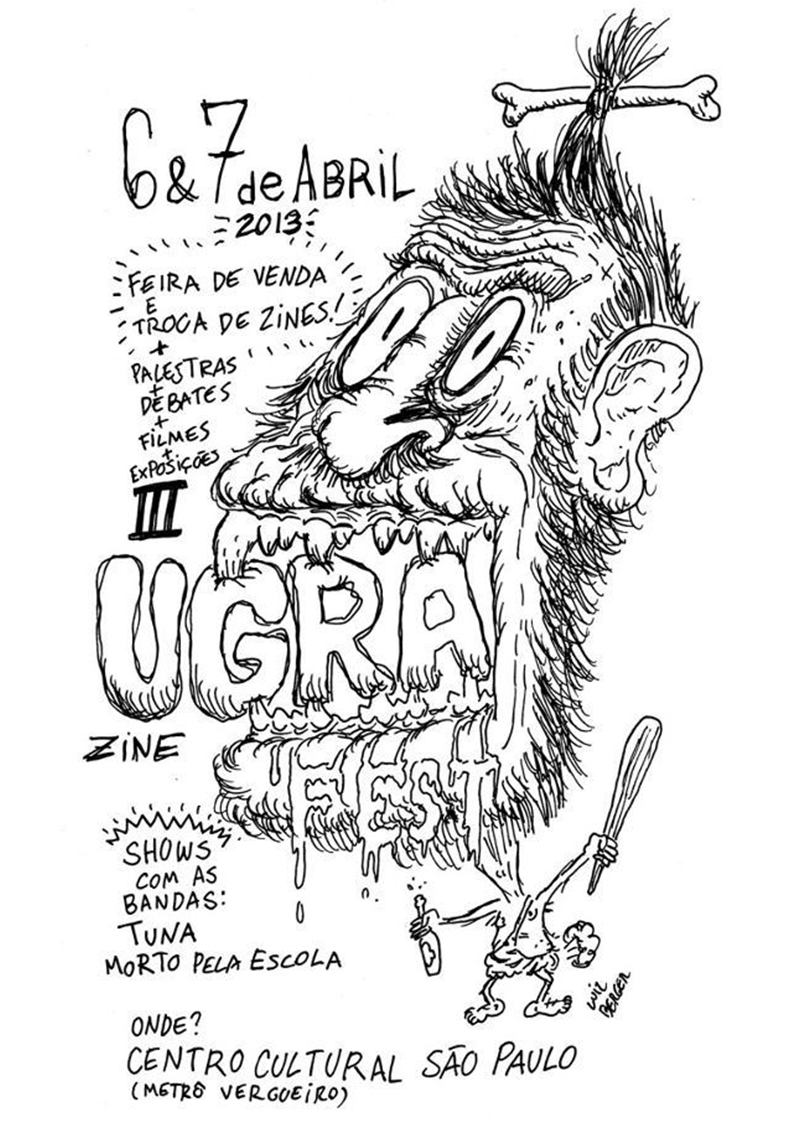

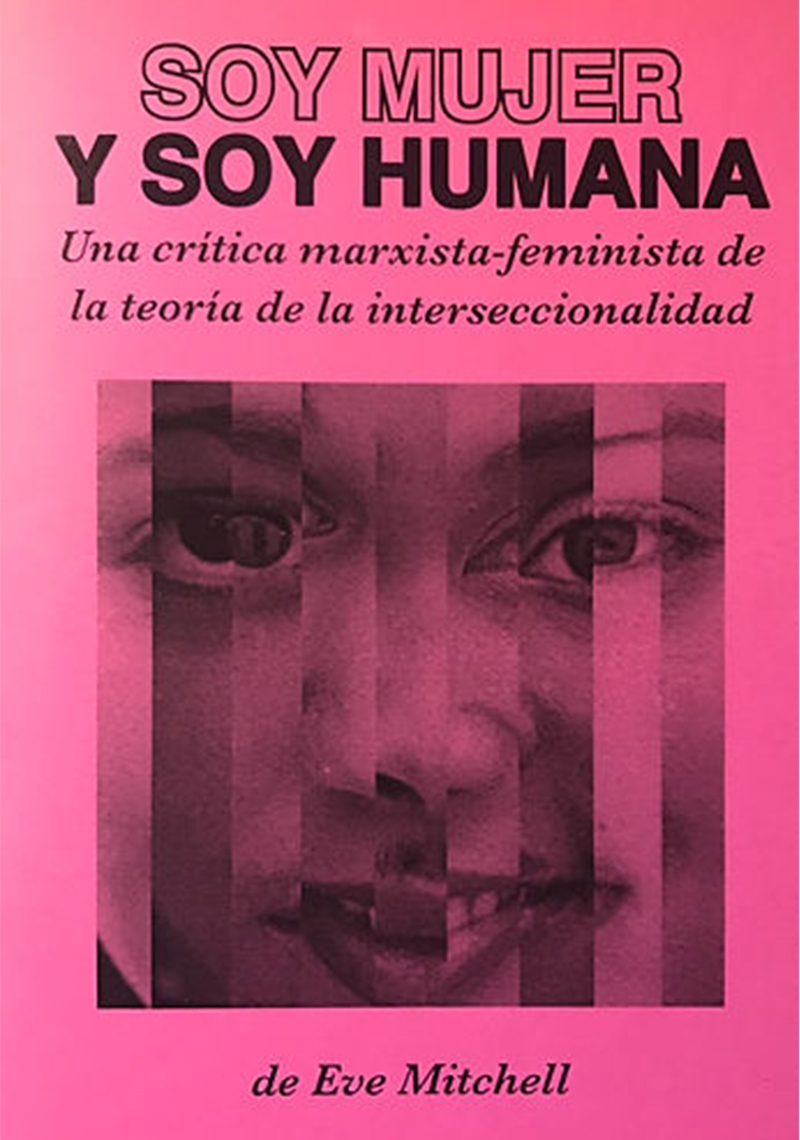

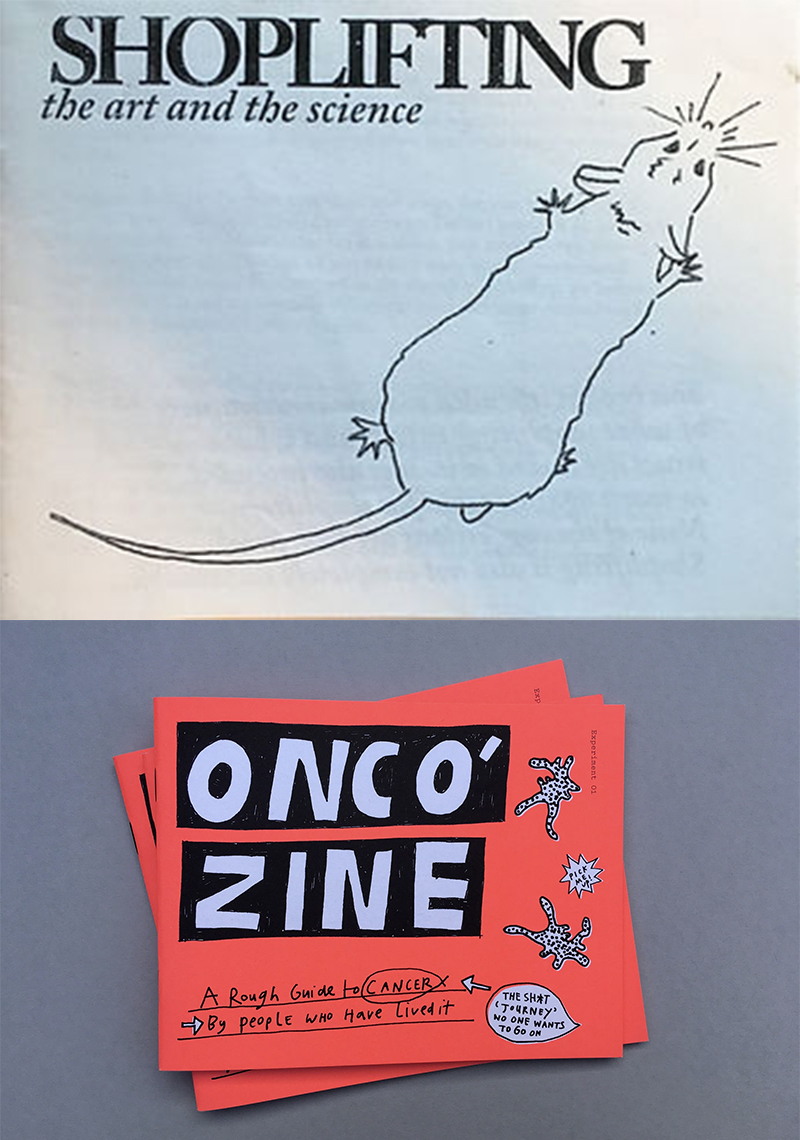

Traditionally associated with the production of short and accessible forms of self-published and DIY magazines, zine making is a practice that is difficult to define for its variety, but has been historically connected to informally printed booklets and pamphlets of an ephemeral nature.

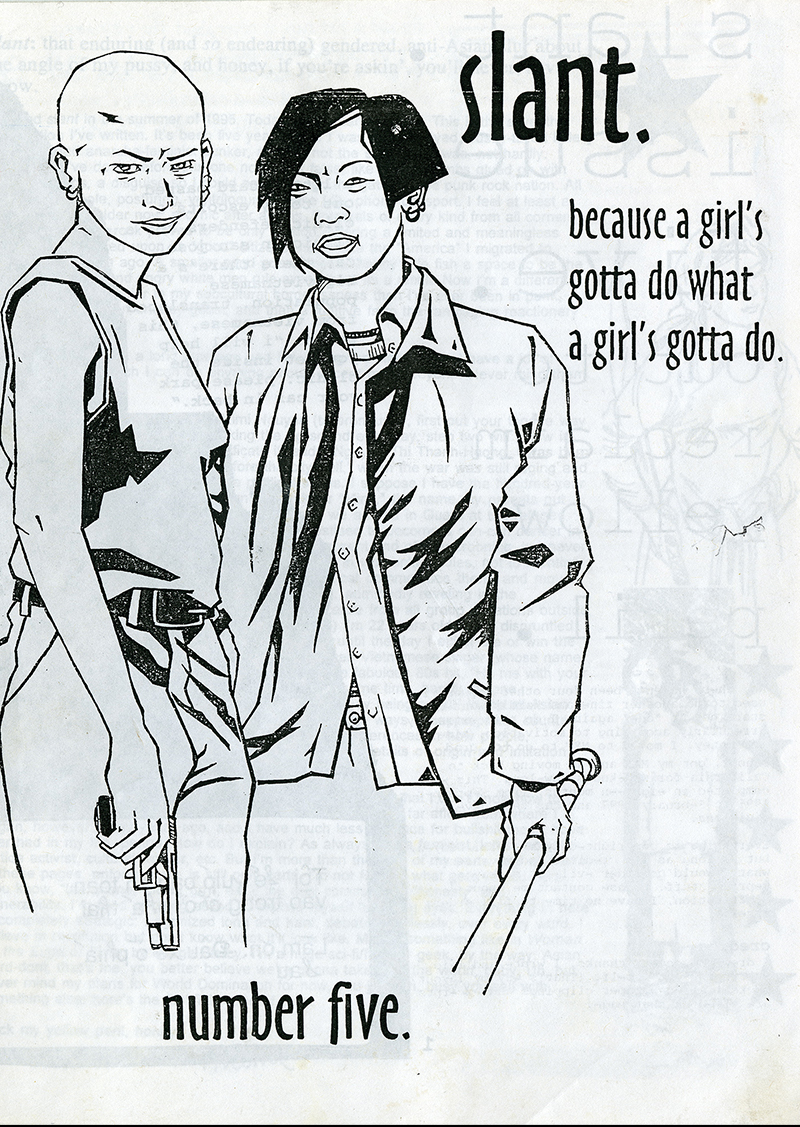

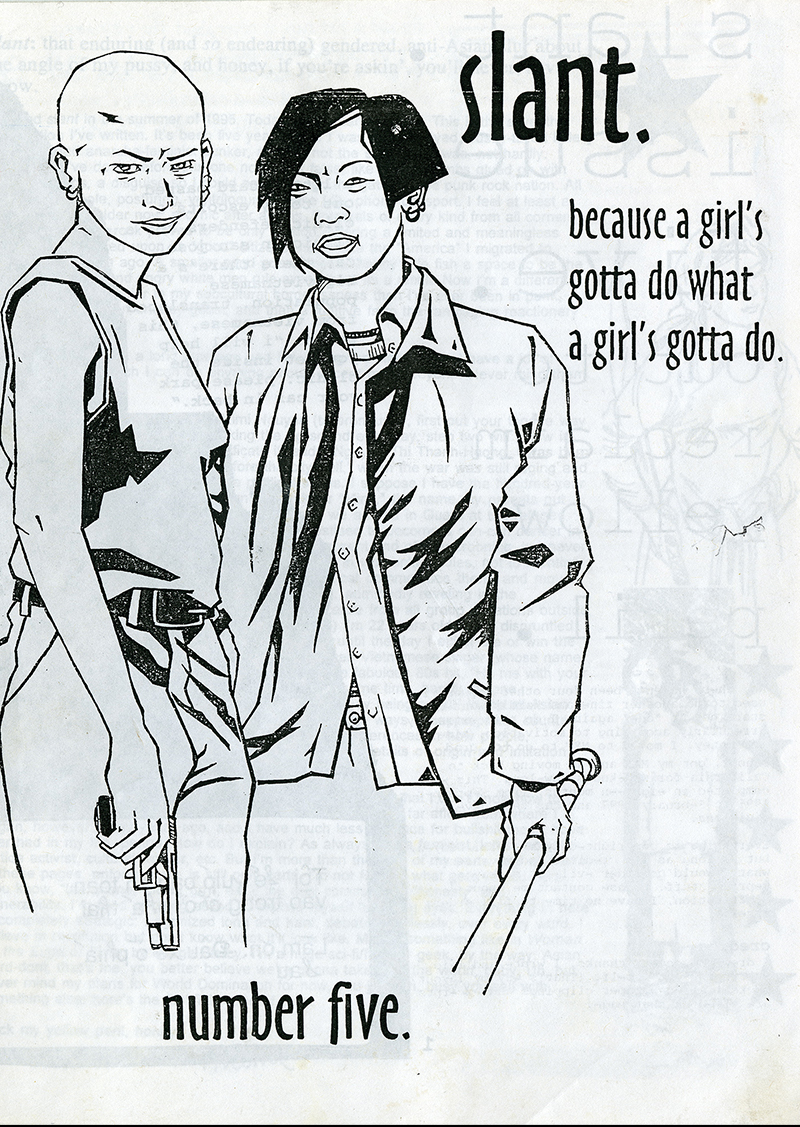

From music to anime, from comics to per-zines (personal zines), zine makers and creators are inspired by anything and everything and such openness of subject matter plays a big part in the appeal of entering this world, which remains largely uncensored.

There isn’t an ‘anything goes’ approach to all aspects of zine culture however, with the format of the zine itself a notorious grey area and not always agreed upon.

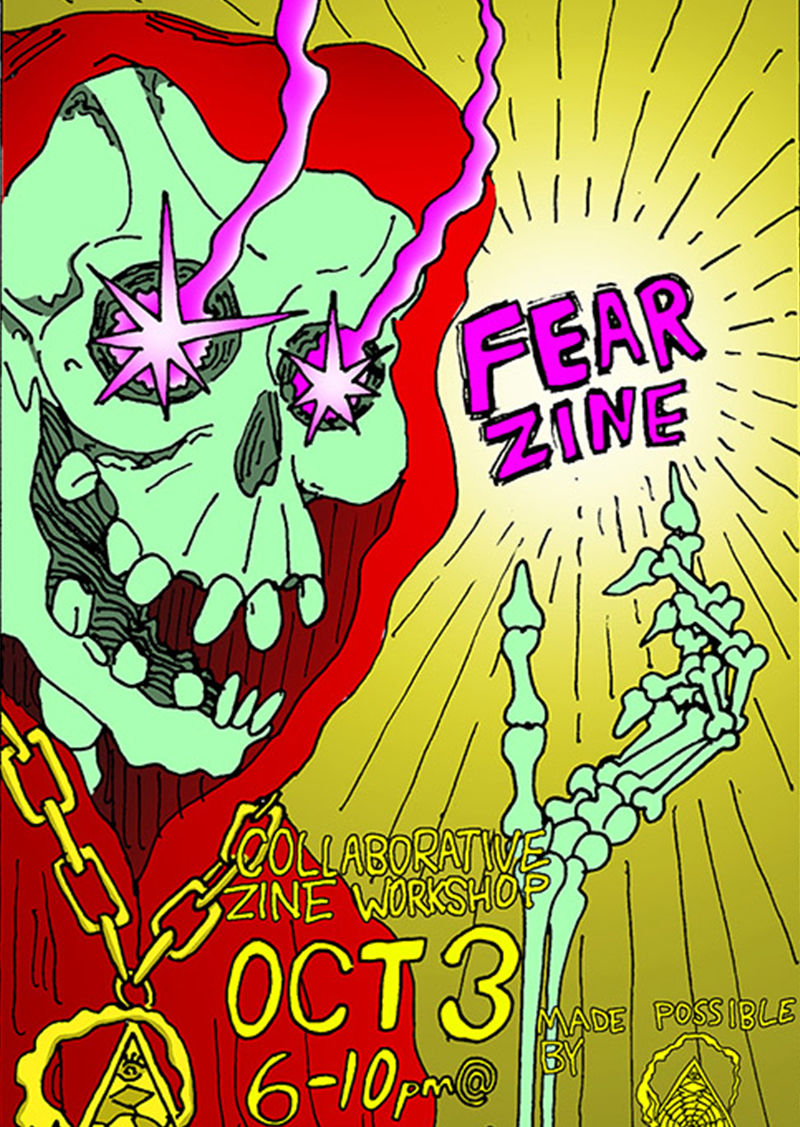

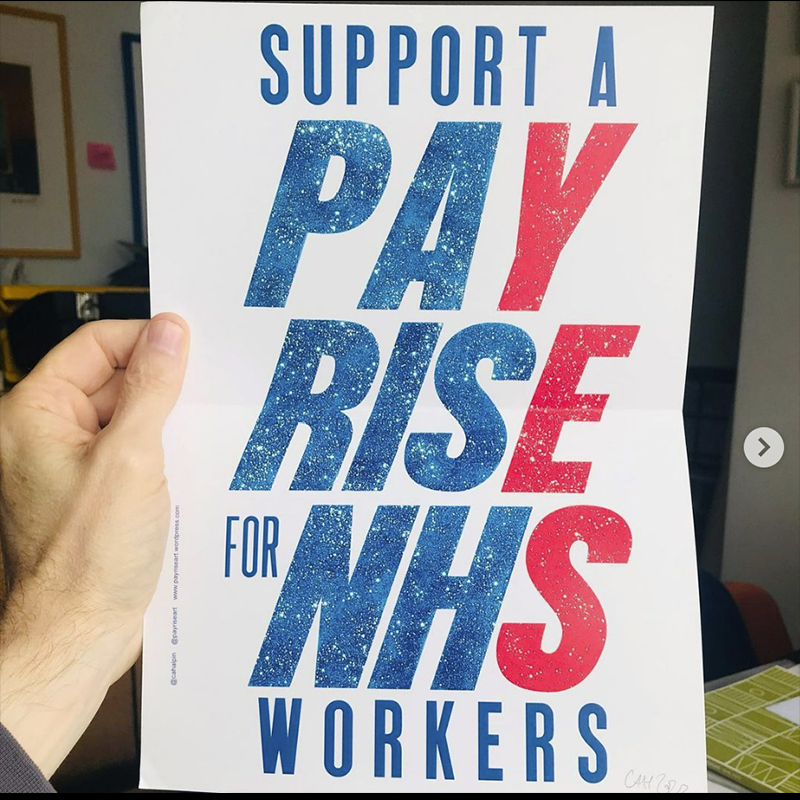

With the freedom to creatively express in an almost uncompromised way, zines allow their creators to continuously push the limitations that are often imposed by more conventional or institutional methods of publishing and communication.

Financial, contextual, political and personal boundaries are through this format questioned and broken, in the emancipatory spirit of makeshift practice and DIY. Abundant experimentation of thought and medium thrives in response to these formal restrictions and the resulting output is of incredible diversity and scope.

The lack of standardisation commonly associated with DIY and makeshift activity, brings a different quality to the self-published space, but with growing tension between the digital and physical production of zines, the very relationship between DIY and handmade becomes less clear, raising interesting questions.

With the freedom to creatively express in an almost uncompromised way, zines allow their creators to continuously push the limitations that are often imposed by more conventional or institutional methods of publishing and communication.

Financial, contextual, political and personal boundaries are through this format questioned and broken, in the emancipatory spirit of makeshift practice and DIY. Abundant experimentation of thought and medium thrives in response to these formal restrictions and the resulting output is of incredible diversity and scope.

The lack of standardisation commonly associated with DIY and makeshift activity, brings a different quality to the self-published space, but with growing tension between the digital and physical production of zines, the very relationship between DIY and handmade becomes less clear, raising interesting questions.

Zine making has origins in a few fairly specific subcultures, role playing game communities, the DIY punk and hardcore scenes, and feminist activism.

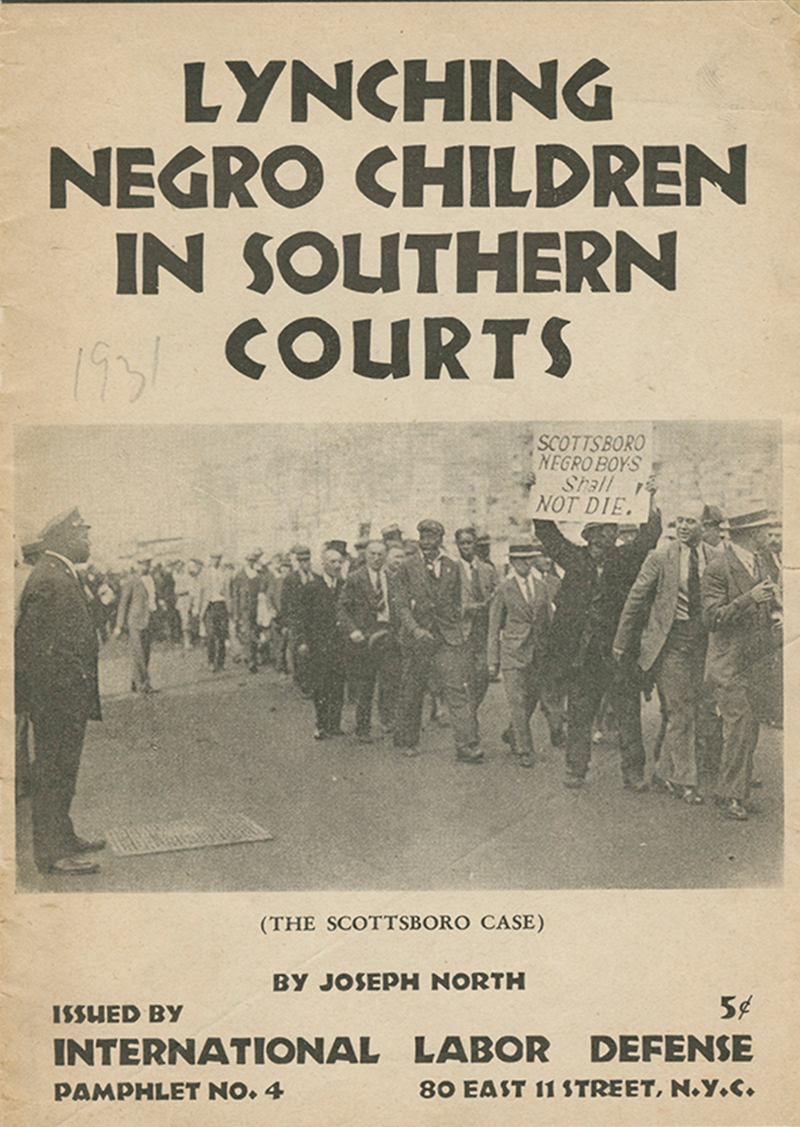

Pre-dating the more accepted ‘zine’ format, pamphlets created and distributed by politically and socially engaged communities were also providing a similar space for content and discussion. A good example of this can be found in early 20th century USA, with black communities sharing lists and maps detailing businesses who were welcoming without discrimination, showing the strong relationship that self-publishing has had with under-represented groups.

Today, making, trading, and sharing zines still fills this role, although some of the discussion has expanded to include additional culturally and socially relevant themes, such as mental health, and wider explorations of gender, sexuality and identity.

Zine making has origins in a few fairly specific subcultures, role playing game communities, the DIY punk and hardcore scenes, and feminist activism.

Pre-dating the more accepted ‘zine’ format, pamphlets created and distributed by politically and socially engaged communities were also providing a similar space for content and discussion. A good example of this can be found in early 20th century USA, with black communities sharing lists and maps detailing businesses who were welcoming without discrimination, showing the strong relationship that self-publishing has had with under-represented groups.

Today, making, trading, and sharing zines still fills this role, although some of the discussion has expanded to include additional culturally and socially relevant themes, such as mental health, and wider explorations of gender, sexuality and identity.

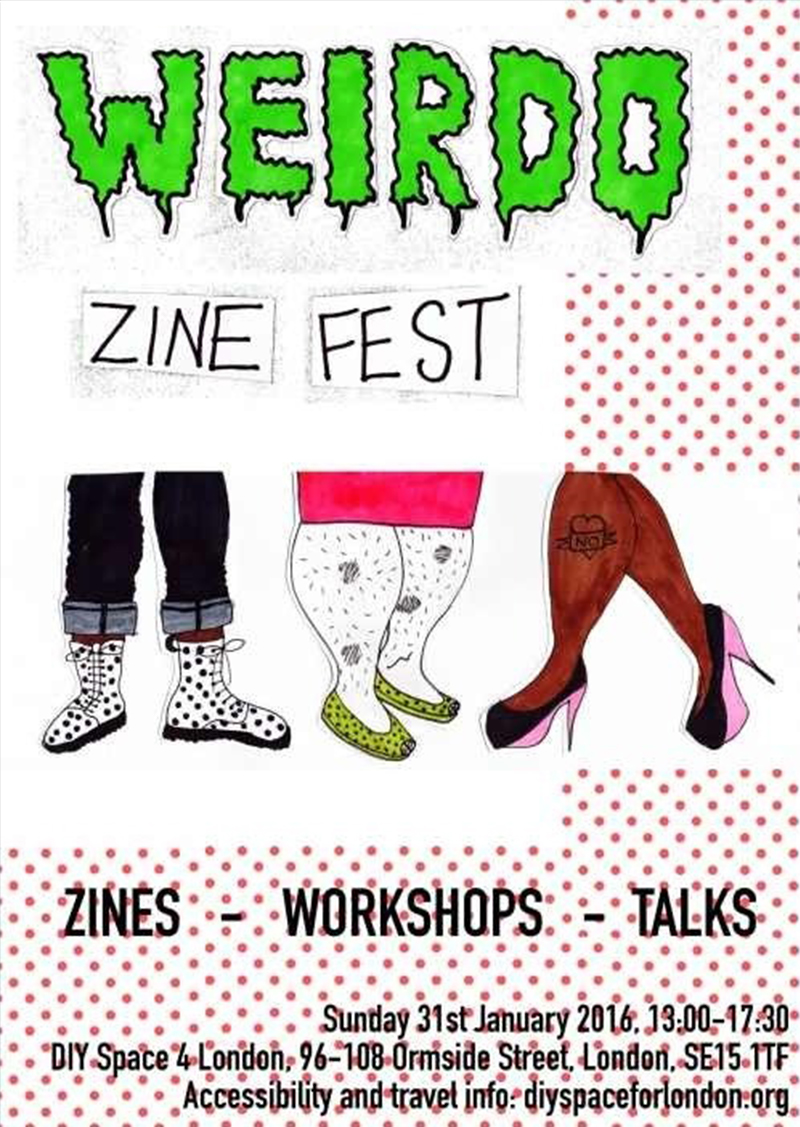

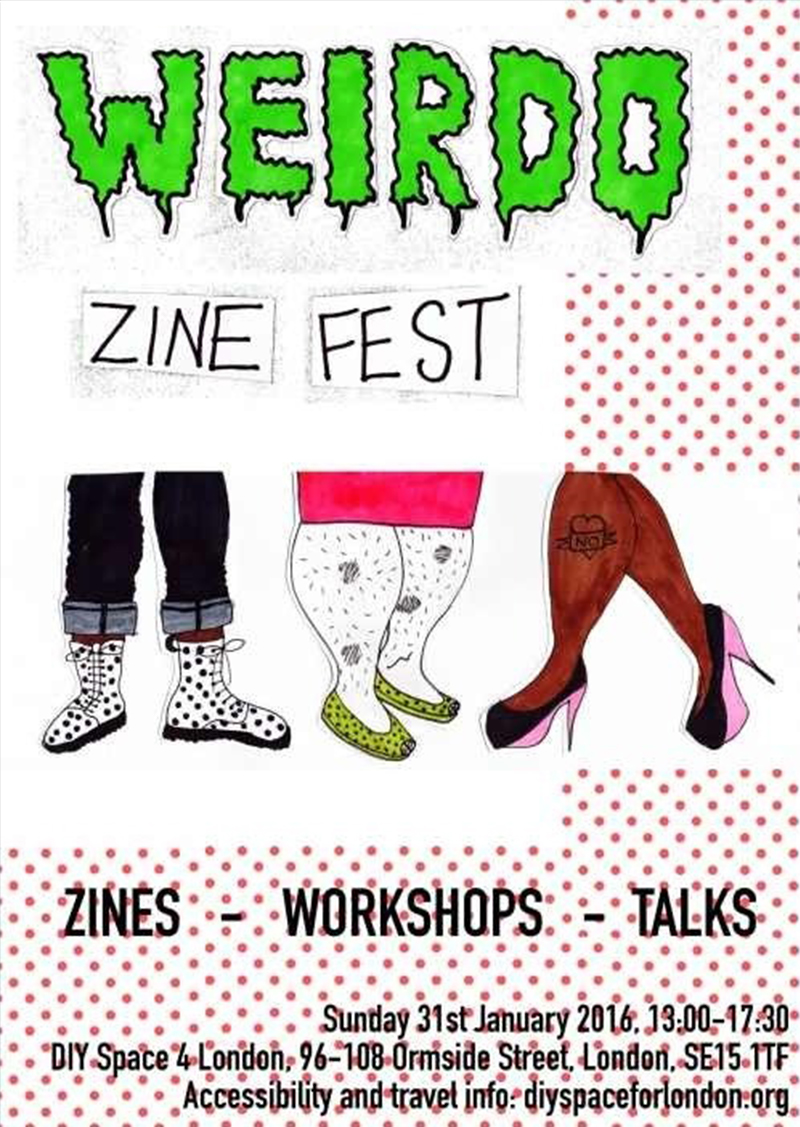

Methods and modes of distribution play a big part in the discoverability of zines. Whilst pre-internet, trading and selling through post mail, at concerts and distros, was the most accessible way to share and see new zine content, now going online offers a level of visibility and reach that is unparalleled.

This hasn’t stopped the relatively recent influx of zine fairs though, showing an unwavering interest in not only the physicality of zines, but also in the interpersonal experience of attaining and sharing zines in environments in which spontaneous discovery can more easily happen than online.

Methods and modes of distribution play a big part in the discoverability of zines. Whilst pre-internet, trading and selling through post mail, at concerts and distros, was the most accessible way to share and see new zine content, now going online offers a level of visibility and reach that is unparalleled.

This hasn’t stopped the relatively recent influx of zine fairs though, showing an unwavering interest in not only the physicality of zines, but also in the interpersonal experience of attaining and sharing zines in environments in which spontaneous discovery can more easily happen than online.

Through social conversations, shared spaces, personal reflections, creation processes and curated materiality, zines offer insights into unique pockets of culture and stories. Pockets that have been documented with full control by those participating.

Libraries and archives, institutional and self-organised within the zine community, have begun to take seriously the potential of zines as first hand accounts of social, political, and economic climates of specific moments, contexts and geographies.

It is in archival practices, of collecting, documenting and storing, that the tension between physical and digital formats emerges again.

The online blog remains an obvious challenger to the printed zine, and there was a moment during the 1990s where popularity in zine making dipped, as the unexplored era of social media and micro blogging began.

But as interfaces and digital sharing spaces grow more and more standardised, and the content that we are able to easily reach is algorithmically controlled, as well as more emphermeal than we originally thought, the offline life of zine communities is thriving.

Through social conversations, shared spaces, personal reflections, creation processes and curated materiality, zines offer insights into unique pockets of culture and stories. Pockets that have been documented with full control by those participating.

Libraries and archives, institutional and self-organised within the zine community, have begun to take seriously the potential of zines as first hand accounts of social, political, and economic climates of specific moments, contexts and geographies.

It is in archival practices, of collecting, documenting and storing, that the tension between physical and digital formats emerges again.

The online blog remains an obvious challenger to the printed zine, and there was a moment during the 1990s where popularity in zine making dipped, as the unexplored era of social media and micro blogging began.

But as interfaces and digital sharing spaces grow more and more standardised, and the content that we are able to easily reach is algorithmically controlled, as well as more emphermeal than we originally thought, the offline life of zine communities is thriving.

The empowering nature of zines, created through the challenging of limitations imposed by mainstream publishing, has made way for a spontaneous makeshift activity that has the ability to transcend waves of major technological advances and obsolescence more effectively than many other forms of media.

It is in this drive towards accessibility and freedom, that the methods, processes and materials informing the creativity of self-published and DIY output take shape. This establishes zines further as significant elements of culture and justifies their continuous evolution through the digital age, offering uncensored open spaces to those who want to get their message out, in the way they want to.

Learn more about it by listening to our podcast episode: zines & self-publishing.

A special thank you to the contributors of this piece, for their time, thoughts, suggestions and resources.

(In order of interview):

Theo Houghtaling – etsy / instagram

Amber Morrison Fox – webpage / etsy

Tyler Haage – instagram

Dagger Han – instagram

Aim Ren Beland – webpage /

instagram

Peter Willis – webpage /

instagram

first published for projektado magazine issue 2: survival and design / august 2022

The empowering nature of zines, created through the challenging of limitations imposed by mainstream publishing, has made way for a spontaneous makeshift activity that has the ability to transcend waves of major technological advances and obsolescence more effectively than many other forms of media.

It is in this drive towards accessibility and freedom, that the methods, processes and materials informing the creativity of self-published and DIY output take shape. This establishes zines further as significant elements of culture and justifies their continuous evolution through the digital age, offering uncensored open spaces to those who want to get their message out, in the way they want to.

Learn more about it by listening to our podcast episode: zines & self-publishing.

A special thank you to the contributors of this piece, for their time, thoughts, suggestions and resources.

(In order of interview):

Theo Houghtaling – etsy / instagram

Amber Morrison Fox – webpage / etsy

Tyler Haage – instagram

Dagger Han – instagram

Aim Ren Beland – webpage /

instagram

Peter Willis – webpage /

instagram

first published for projektado magazine issue 2: survival and design / august 2022

Credits: Tate Zine Archive

There have been attempts to create rough guidelines, which aim to help create a stronger definition between zines and other published material, as a way to protect the ‘makeshift’ spirit of this activity. These include for example, limits to the amount of copies produced, distribution methods, and price.

But often these attempts seem to reduce the definition of this practice to technical oriented guidelines, at times failing to consider fundamental aspects of zine making, like the communities they speak to, their content, and the role they play in the creator’s life.

modal 7

—

content

modal 8

—

content

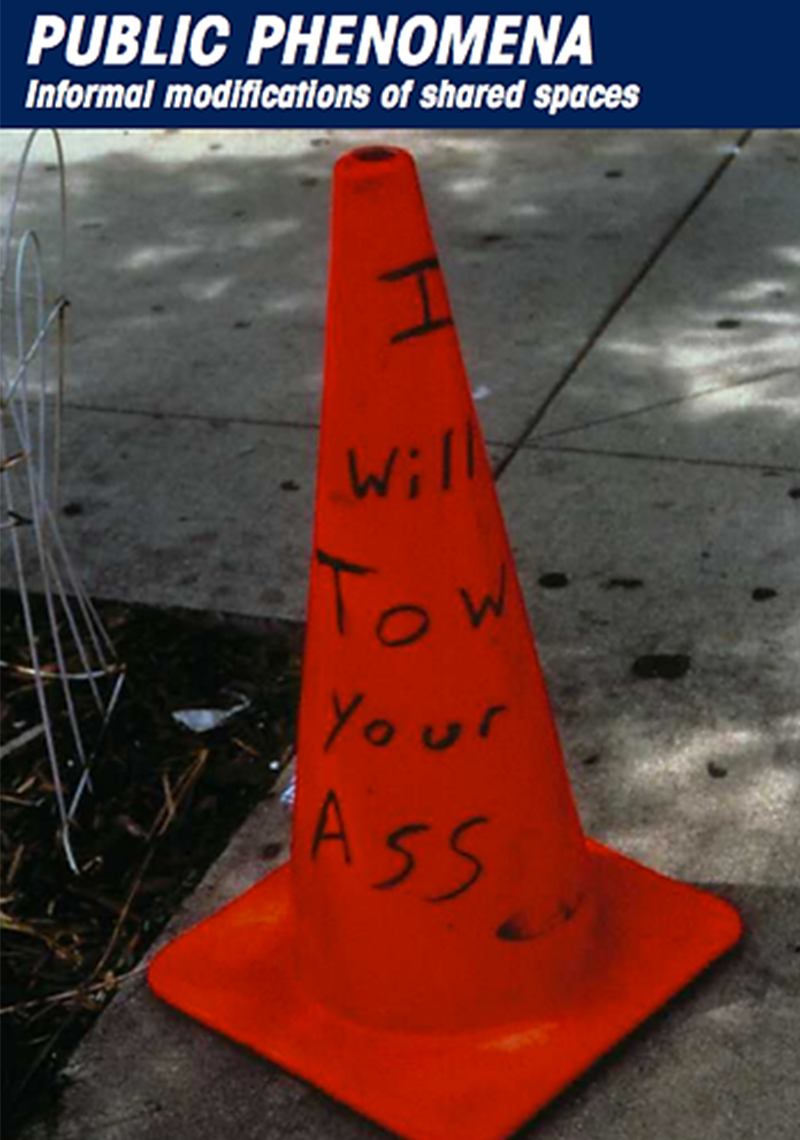

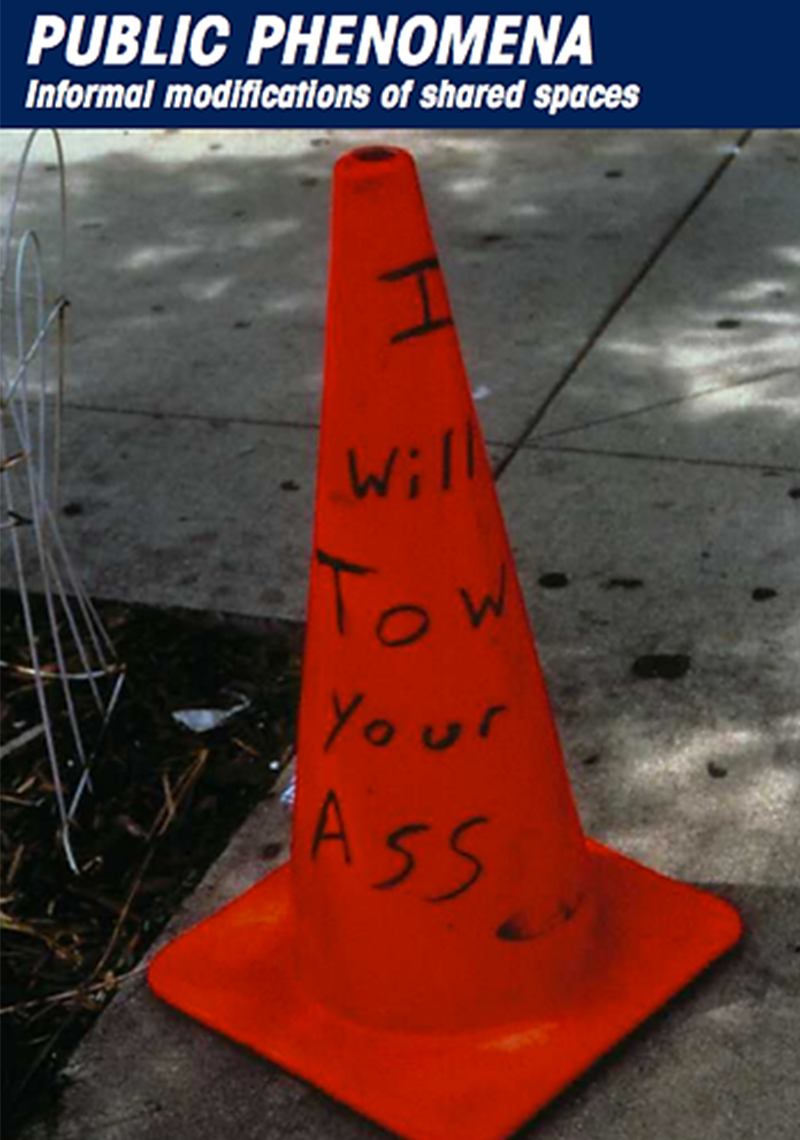

The appropriation of products, materials, and practices abstract from their intended use, is an occurrence that is commonly found in a wide range of human contexts. Being it the use of a book to steady a table wobble, the salvage of bomb shells to craft canoes, or the reclamation of car tyres to erect walls. Makeshift activity emerges from a combination of creativity and what are perceived to be limitations to those defining the activity as such. The nature of such limitations can be varied: it could be associated to a lack of resources (financial, material, human, natural), or to a spatial or temporal constraint, or to any other factor considered to be limiting to the ability to perform the desired activity in the way it is presumed to be conventional.

Makeshift is therefore a word that does not only span across different scales and contexts, but also through complex layers of interpretation, as what is considered the result of limited resources and an act of creative adaptation by some, may be normality and efficiency to others, a practice woven and rooted into their social, economic, and cultural fabrics.

For their complexity and variety, such activities evoke an equally wide array of emotional and intellectual reactions from observers depending on the context, scale, legality, ingenuity and vested interests. All describing an innate instinct for humans to be able to use what is at hand, to create a scenario that improves their chances of survival—be it to build in order to protect a community, improvise to secure potential financial stability, reuse to avoid an unnecessary contribution to landfill, adapt to respond to a changing environment, or repair to be able to extend life.

As these reactive and spontaneous acts often surface in contexts recognised outside the formal boundaries of design, it seems appropriate to dedicate a part of our survival and design project to identifying and telling the stories of such instances and the people involved in them.

‘Makeshift tales’ is a podcast series that offers an opportunity to find not only engaging and inspiring, but also unexpected, novel and ingenious examples of human resilience, and serves as the first part of our year-long exploration into the theme of survival.

This episode of makeshift tales visits a slice of the international community of zine making, a self-initiated DIY activity that has historical roots in the dissemination of stories, thoughts, art and insights between subcultures and under-represented communities who typically do not get a voice in mainstream press and published media.

We explore the motivations for DIY zines and self-publishing in physical print today, in a context that is accelerating towards digital production and content, the unique archival opportunities it presents, and the creation of valuable pockets of self-initiated social spaces that combine creativity, collectivity and sharing. Learn More

Episode 2 of makeshift tales presents a brief analysis of the context of Cuba, its social and political history and hardships, and how over a span of about 60 years this has shaped the behaviours and material culture of the people of Cuba.

When discussing makeshift practices, and more specifically design practices that aren’t universally recognised as such, collective experiences of limitations and necessity can often provide insights into alternative approaches to design activity. Cuba remains an important example of these phenomena, and represents an extensive source of knowledge on alternative ways of participating in the shaping of everyday practices.

Through a conversation with Joe Purvis and César Beuve-Méry, two expats who lived for part of their childhood and adolescence in Cuba, daily life and the legacy of economic hardship is dissected through the lens of design and physicality. Learn More

Episode 1 of makeshift tales presents TXTmob – a conversation with design professor and activist Tad Hirsch, on the creation of a decentralised communication system born out of political dissent.

Designed, implemented and used by the protesters of the 2004 Democratic and Republican National Conventions in Boston and New York City, TXTmob is an SMS (Short Message Service) based communication system that predated widespread use of smartphones. It protected users’ anonymity while offering real-time and extensive reach within the network of protesters, enabling organisational efforts and reportage on police movements, and helping to bolster solidarity during the demonstrations. This often unknown design activist project contains key elements that were instrumental towards the development of the platform we know today as Twitter. Learn More

As an introduction to Makeshift Tales, episode 0 is a record of the very beginning of our journey into the concept of makeshift: an informal chat we had as a collective during the summer of 2021, where the question “what is spontaneity?” was raised in reference to makeshift practices.

The following conversation presents selected parts of the discussion, where we unravel the intricacies of this crucial concept, and in doing so, form a shared understanding of it. Although originally recorded for archival purposes, we decided to make it available, as it seemed to be a thought-provoking prelude for what will come next.

episode 4 coming soon