This article hopes to ignite inquiries and criticality in the way architecture is currently practiced. Indeed, as a profession, it is deeply entrenched in neoliberal, colonial, heteropatriarchal systems, rooted on the domination and centralisation of cis, white, heterosexual males. This overrepresentation in the creation of the built fabric increasingly anonymises minority groups. While feminist theory as a whole provides useful tools to deconstruct the heteropatriarchy reflected within spatial design, it remains firmly rooted and dominated by whiteness. Alternatively, Black Feminism, specifically Kimberley Crenshaw’s (1991) seminal work on intersectionality, offers ways of understanding space in interlocking ways, to ponder over the ways in which systems of domination simultaneously shape space, exclude and anonymise. Black Feminism gives clues on possibilities for radical intersectional action, and allows us to see Black space as a site of “very real deprivation and oppression, [but] simultaneously a site of resistance and possibility” (Tayob, 2018: 206). Rethinking architecture through a black feminist lens offers possibilities for decolonial, intersectional feminist architectural practice, for a holistically care-centred practice. This paper fundamentally sees the latter as an urgent tool to provide a complete transformation of the architectural profession, to fight for radical healing and social justice.

Architecture and urban design are deeply entrenched in neoliberal, colonial, heteropatriarchal systems, rooted on the domination and centralisation of cis, white, heterosexual males. This overrepresentation in the creation of the built fabric increasingly anonymises minority groups. While feminist theory as a whole provides useful tools to deconstruct the heteropatriarchy reflected within spatial design, it remains firmly rooted and dominated by whiteness. Alternatively, Black Feminism, specifically Kimberley Crenshaw’s seminal work on intersectionality, offers opportunities to understand space in interlocking ways, to ponder over which systems of domination simultaneously shape space, exclude and anonymise.

Though rooted in the 1960’s feminist movement of African-American women in the United States, I understand Black Feminism as the political and collective theories and actions by black women around the world against contextual structural manifestation of racism and patriarchy. Black Feminism also rethinks and respatialises structures of racial and heteropatriarchal inequalities, contesting current hegemonic spatial design practices. As a black female myself, Black feminism as a discipline made me feel seen within feminist discourse, vocalising the interwoven barriers faced by black women.

Here I am claiming feminism to willingly dare to elicit discomfort and radically challenge accepted systems within the architectural profession. Black Feminism gives clues on possibilities for radical intersectional resistance and action. Thus, rethinking spatial design through a black feminist lens offers possibilities to rethink architectural practice in a decolonial, intersectional and holistically care-centred manner. Through the analysis of under-visibilised existing care systems practices engineered by black women as spatial resistance, in this article I am arguing for radical care as an urgent tool to provide a complete transformation of the architectural and urban design profession, fighting for radical healing and social justice.

resistance black feminism allows us to envision

Black women have largely contributed to a geography of resistance. bell hooks, one of the most prominent authors of Black Feminism, indicates that marginal and central spaces exist both in physical and metaphorical senses. Black women navigate between intimate violence spatialised in the home and institutional and patriarchal violence in the streets. In Urban Black women and the politics of Resistance, Isoke argues that: “black women create geographies of resistance that undermine structural intersectionality—convergent systems of race, class, sexual, and gender violence.”

Black women sustain this resistance through the dissemination of new socio-spatial meanings, providing counter narratives to hegemonic metanarratives through communal engagement and action. In our communities, we have a nurturing role, one of community mothering, that instead of destroying, seeks doing politics through reclaiming, re-envisioning, vitalising and transforming the social and built environment. And this is what I believe an architecture through a black feminist lens should aim to do. Cripps (2004) convincingly argues that

“[a]s practitioners, architects are involved in the upgrading, modernisation, and regeneration of the urban fabric, tend to work intuitively, have little time to reflect and so they continue with orthodox ways. Barriers to access of black and minority ethnic people to practice continue to be ignored, and in a profession which is white and male dominated, the pretence that there is a ‘modernity’ which supersedes culture also serves to perpetuate European and North American hegemony in the field”.

Architects thus need to be critical and reflective, from early community research to post-occupancy assessment, taking in the lessons that each project brings about. This also includes reflecting over the ways interviews are conducted, and promotions offered. In Practice and in Education, Timothy Onyenobi, member of the RIBA Architects for Change advisory group, advises for more blindness in the process, to have BAME interviewers for BAME students, to increasingly include diversity training and unconscious bias. When people of colour are actually hired, how is the practice ensuring they will not be faced with daily microaggressions? Or, as Danah Abdullah pertinently stated in 2019: “it’s important not just to bring people to the table, but also to ask yourself, what sort of seat are you offering?”.

While attempts at gender equality have been made in the profession, they remain looked at in isolation. Change ought to be intersectional if it is to benefit all. Indeed, looking at it through an intersectional lens, black females are almost absent proportionately from the architecture profession. Alicia Olushola Ajayi, African-American architect and researcher is correct in saying that “when we (black women) become licensed architects, it becomes history.” Indeed, in the US, 0.2% of licensed architects are black females, in the UK, that is 0.6% of ARB chartered architects in 2019. Here it is necessary to rely on Leslie Lokko, who cogently argues that “in architecture, as in other disciplines, the question of whose pleasures are pursued, who gets to build what, whose histories and experiences are represented and whose voice is heard—is largely inextricable from the more complex question of identity”1.

Minority identities should be seen, represented and dignified through the built fabric, which is only possible when we are granted responsibility for participating in the design of said built fabric. Diversity goes beyond appearance and is about long lasting meaningful change. Identity plurality ought to be reflected in the profession as it allows an inclusive answer to the question: Who is good enough to imagine the future, who is allowed to dream it?

New feminist collectives led by black women have emerged, working intersectionally to dismantle spatial violence, tackle spatial injustices as well as to design more equitable and inclusive spaces and cities. ‘Black Females in Architecture’ was created in 2018 by Akua Danso, Neba Sere, Selasi Setufe and Alisha Morenike Fisher to raise the visibility of black women in the built environment. Through the creation of safe spaces for black female architects as well as numerous events and discussions within the profession’s largest institutions, the collective aims to address issues of inequality and diversity within built environment professions. Similarly, Matri-Archi(tecture), was founded by Khensani de Klerk and Solange Mvafeno as an intersectional collective bringing African women of colour together for the development of spatial education across African cities. Through their writing, talks, podcasts and design practice, Matri-Archi encourages critical rethinking of city-making and knowledge production.

Black Females in Architecture

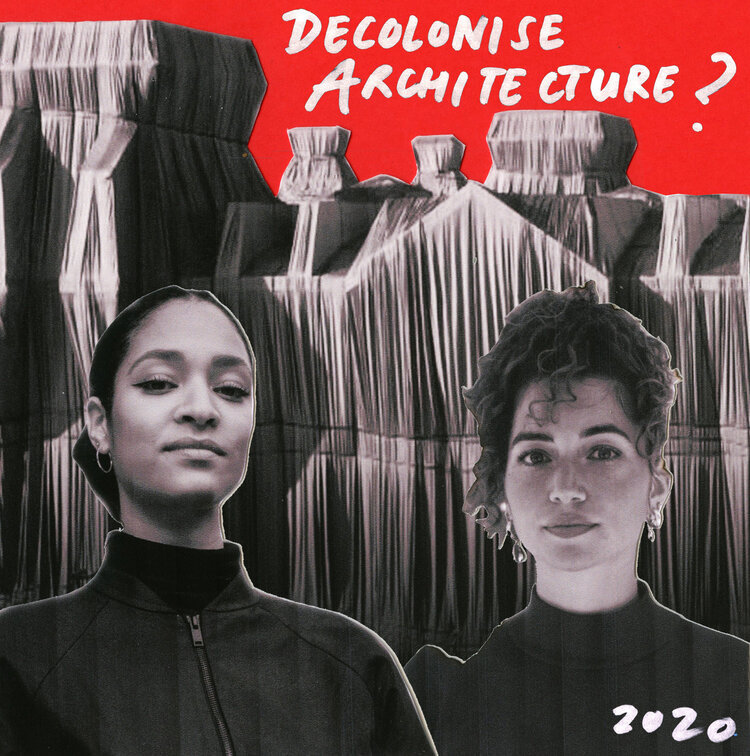

AF 100 DAY STUDIO: DECOLONISE ARCHITECTURE?

decoloniality: telling the past inclusively, so we can all imagine the future

Beyond diversity and inclusion, which are crucial, this piece calls for complete decoloniality in practice. Decolonial and intersectional feminism are also fights for epistemic justice. Decoloniality challenges how we think altogether, it allows us to infuse our profession with new forms of meaning. Inclusion within flawed systems will not lead to sustainable change. For it, a complete rethinking of the structure itself appears necessary.

Architectural education also needs to be rethought. It ought to be more diverse and inclusive, to recognise historically and contemporarily the diverse groups of people contributing to the construction of the built environment. Architectural theory and history should present buildings “as sociocultural objects and architecture as an artifact of social, cultural, economic, and political phenomena that mirror societies at certain points in time”2, stimulating a multicultural and post-colonial approach. Indeed, the contribution of women, queer, black and racialised voices need to find their place within the canon. Following Lokko3: “History, in this instance, is clear: blacks, either as Africans or as diasporic cultures, have historically had nothing to say about architecture—as a consequence, architecture has had little to say in response” .This urges a change.

Eurocentric classical and modern architecture emblematised universalism. The limits of the latter are to homogenise heterogeneities, to legitimise standardisation of space and proportions and even the body and identity, eventually resulting in the erasure of minority aspirations in favour of the white majority. Those limits are as true in Feminism as they are in Architecture. Indeed, colonisation across the world lied on the false pretense of a civilising mission in which the modern European aesthetics was to be spread, as portrayed universally best to respond to all local contexts. The limits of that reasoning are today clear but its legacy has not been challenged enough in architectural practice and education. Decoloniality in Education means a non-tokenistic inclusion of works from Global South architects, urban designers and researchers into our curricula. It includes holding the work of intersectional voices to the same standard as white male ones. Decoloniality hopes to shatter the precept of the white spatial imaginary being the only valid imaginary, the only valid form of taste. We need to allow everyone to dream about the future. Change, new possibilities and inclusive futures can happen; only if we care enough to let them.

a new duty of care

When employed, an architect has a legal duty to use reasonable skill and care through their work. Arguably, the benchmark for reasonable care is dependent on the rest of the profession and care is not necessarily understood in a feminist sense but rather as an absence of excessive negligence. I posit the need for a new duty of care, one that extends beyond the building process, to a duty of care to society as a whole.

As per Black feminist thought, care can be a potent tool of resistance. bell hooks considers care and affection as useful tools to comprehend race. As part of a more holistic, race-conscious practice, architects need to be more cognisant of the systems they work in. Prior to embarking on a project, key questions should be asked as exercise of caring due diligence, as a duty of care to society: Who is the project displacing? Who and what is it erasing? What assumptions have already been made? How does it affect the overall development of the area? What is imagined, who imagines it? Who is the project for and operated by whom?

Feminist literature around care has tended to be dominated by whiteness. As aforementioned, black feminism offers a dimension of intersectionality and political strength. Specifically, the politics of homemaking, that have characterised black feminist spatiality, bears significance. Homemaking has a communal dimension, it centres connectedness and interdependency. It transforms an often violent space into a home place, a space of belonging and resistance for the community. Describing the work of black female activists in Newark, Isoke4 describes those women who “transform(ed) blighted cityscapes into culturally symbolic homeplaces that nurture the life chances, leadership capacity of political efficacy of an emerging generation of activists.” This nurturing potential and ability is one I believe can be harnessed by architects and urban designers.

Integrating aspects of care into architecture and urban design is also critical in order to address the climate crisis (Klein, 2019). A failure to do so risks further oppressing certain groups in a fight against something they are already disproportionately affected by. Capitalism and Neoliberalism have led new developments to displace poorer communities of colour. With the pretense of climate action, a phenomenon known as green gentrification has begun to take place, using projects for the creation, restoration and beautification of green spaces as the lure to attract wealthy white populations, rising housing costs and usually displacing long-term low income residents and people of colour. Architects can thus directly cause significant cultural erasure, eliminating ethnic shops and cultural spaces in favour of new modern and so-called green redevelopments. As a result, lower income housing is pushed to more deprived and polluted areas, with the majority of social housing in the UK being located near extremely busy streets. In 2013, 9-year-old Ella Kissi-debrah died of an asthma attack in Lewisham, directly caused by dangerous air pollution. Spatial health inequalities are all the more visible nowadays, with higher rates of COVID-19 contamination among people of colour in the UK and US.

I advocate here for radical intersectional care processes, as argued in Black feminist literature, to be imbued into architectural work. Indeed, I am in unison with Naomi Klein who calls for a green new deal that works to provide solutions against racial and gender inequalities, working on a society based on care and repair; and I make Tronto’s words as mine when she pertinently states that “we now need an architecture that fulfills the basic tasks of sharing responsibilities for caring for our world, an architecture that is sensitive to the values of repair, of preservation, of maintaining all forms of life and the planet itself.”

conclusion

Therefore, this article is my attempt to make the case for a re-evaluation of spatial design and architecture through the lens of Black Feminism. Doing so allows a comprehension of the intersectional spatial violence architects can be complicit in propagating and the means through which they can begin to fight it. Nevertheless, by no means, am I inferring that architecture alone can dismantle deeply ingrained structural systems of oppression. But I believe it can choose to work either alongside or against those systems. Hitherto anonymised communities need to be heard, seen, represented and dignified within the built environment. The makeup of the profession as well as the curriculum ought to be reflective of all.

The Black feminist spatial imagination actively works in ways that are anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-classist, anti-homophobic, continuously fighting the oppressions of neoliberalism and colonialism. Intersectional thinking is indeed indispensable to the design profession as a whole. Understanding equally entangled oppressive processes is the only way to begin to dismantle them. Through this article, I acknowledge intersectionality, solidarity and care, as radical agents to incorporate within spatial design. I dare to hope that architects can design our cities with care at their heart. Black feminism has taught me that resistance and resilience are possible, that caring through our work is necessary; more so, I believe it’s the only way to holistically design with the planet in mind and without leaving anyone out. The past year has shown us that it was high time for change. It’s now time for a better, brighter, and more inclusive future in the architectural profession.

footnotes + references

1 + 3/ Lokko, L. (2000) White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture Race and Culture,

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

2/ Gürel, Meltem Ö. and Katheryn H. Anthony (2006), ‘The Canon and the Void: Gender, race, and architectural history texts’, Journal of Architectural Education, 59(3), p.66–76.

4/ Isoke, Z. (2012) Urban Black women and the politics of resistance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Black Females in Architecture BFA (2020) Why BFA?. [Online] Available from: https://www.blackfemarc.com/why-bfa

Booth, E. (2018) Architecture needs to acknowledge it has an issue with race. The Architect’s Journal. [Online]. 9th May 2018. Available from: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/opinion/architecture-needs-to-acknowledge-it-has-an-issue-with-race

Crenshaw, K. (1991) Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43, p.1241–1299

Cripps, C. (2004), Architecture, Race, Identity, and Multiculturalism: A radical ‘White’ perspective, Social Identities, 10(4), p.469–481

Ducre, K. (2018) The Black feminist spatial imagination and an intersectional environmental justice, Environmental Sociology, 4(1), p.22-35

Escobar, A. (2018) Design for the Pluriverse. Durham: Duke University Press

Gang of witches (2020) Feminism and Ecology: The Same struggle? With Marijke Colle. [Online]. December 2020. Available from: https://podcast.ausha.co/gang-of-witches-ibiza-podcast/1-feminism-and-ecology-the-same-struggle

Gökarıksel, B., Hawkins, M., Neubert, C., Smith S. (2021) Feminist Geography Unbound: Discomfort, bodies and prefigured futures. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2021

Hooks, B. (1984) Feminist Theory: From Margin to the Centre, Boston: South End Press

Hooks, B. (2009) Belonging: a culture of place. London: Routledge.

Hunt, E. (2019) City with a female face: How Vienna was shaped by women.The Guardian. [Online]. 14th May 2019, Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/may/14/city-with-a-female-face-how-modern-vienna-was-shaped-by-women

Kern, L. (2020) Feminist City: Claiming space in a man-made world. London: Verso

Khandwala, A. (2019) What Does It Mean to Decolonize Design? Dismantling design history 101. [Online] Available from: https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/

Klein, N. (2019) On Fire: The Burning Case for the Green New Deal. Bristol: Allen Lane

McKittrick, K. (2006) Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mollett, S., Faria, C. (2018) The spatialities of intersectional thinking: fashioning feminist geographic futures, Gender, Place & Culture, 25(4), 565-577

Perera, J. (2019) The London Clearances_ Race, Housing and Policing. Institute of Race Relations, Background Paper 12 (1)

Puig de La Bellacasa, M. (2017) Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

The Funambulist (2016) Design & Racism / Questions and Roundtable with Alicia Olushula Ajayi, Christina Heatherton, Hadeel Khalil Assali and Minh-Ha T. Pham. 14th May 2016 [Online] Available from: https://soundcloud.com/the-funambulist/the-funambulist-design-racism-questions-and-roundtable

Tronto, J. (2019) Caring Architecture. In: Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet. Boston: MIT Press

Vergès, F. (2019) Un féminisme décolonial. Paris: La Fabrique

Wainwright, O. (2020) ‘People Say we don’t exist’: the scandal of excluded black architects. The Guardian. [Online]. 23rd July 2020. Available from: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/architecture-is-systemically-racist-so-what-is-the-profession-going-to-do-about-it

Waite, R. (2020) Architecture is systemically racist. So what is the profession going to

do about it?.The Architect’s Journal [Online] 7th July 2020. Available from: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/architecture-is-systemically-racist-so-what-is-the-profession-going-to-do-about-it

Winkler, T. (2018) Black texts on white paper: Learning to see resistant texts as an approach towards decolonising planning. Planning Theory, 17(4) 588–604

author

Aïssatou completed her undergraduate studies in Architecture at the University of Bath. She holds an MSc from the Bartlett’s Development Planning Unit, UCL and is currently reading a M.Arch degree at the London School of Architecture (LSA). Aïssatou has worked for various architecture offices, on projects in the UK, Switzerland, France, Niger and Tanzania.

Born in Geneva to Guinean parents, she has always had a keen interest in social justice and international development which she pursued across several professional and volunteering experiences; working for the Red Cross, UN, in the Calais refugee camp, for the construction of social houses in Costa Rica, and as an Architectural Assistant for humanitarian architecture Charity Article 25. She recently co-founded REDD collective with fellow LSA students to explore intersections of spatial and social justice in London. Their disruptive work explores issues of race, gender and sexuality and how these intersect and affect the experience of space.

first published for projektado magazine issue 1: anonymity in design / may 2021