creating tools for exerting our rights to protest

english (translation) // 9th November 2020. Peru is facing its biggest social, economic and health crisis in decades due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the Peruvian Congress majority parties carried out a legislative coup, overtook power, and formed an illegitimate authoritarian government. These events sparked a series of massive protests, in which we Peruvian citizens exerted our right to insurgency and defended our democracy. The result was an overwhelming 37% of the Peruvian population participating in the demonstrations in some way: in person, digitally or from home. (IEP, 2020).

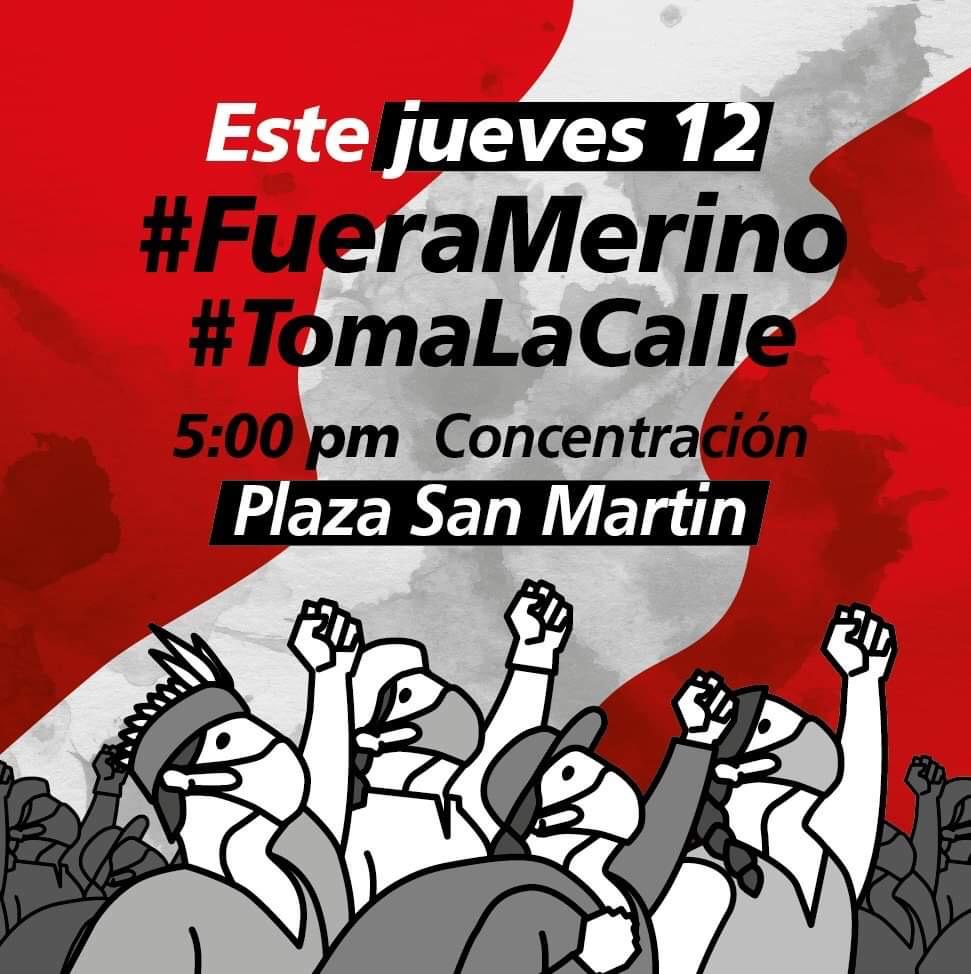

During these days, many activists created tools and platforms to facilitate safer and more effective demonstrations: Instagram profiles with collections of pictures and videos of the protests; guides for the digital protection of activists; Google Drive folders containing insurgent illustrations; Telegram chatbots for supporting protesters; and powerful messages spreading through TikTok, Whatsapp and Facebook offering invitations to join the demonstrations.

spanish (original) // 9 de noviembre de 2020. Perú enfrenta su mayor crisis social, económica y de salud en décadas debido a la pandemia de la COVID-19. Mientras tanto, la mayoría partidaria del Congreso peruano llevó a cabo un golpe de estado legislativo, tomó el poder y formó un gobierno autoritario ilegítimo. Estos hechos provocaron una serie de protestas masivas en que los ciudadanos peruanos ejercieron su derecho a la protesta y defendieron la democracia. Un abrumador 37% de la población peruana participó en las manifestaciones de alguna manera, sea digital, presencial o desde sus casas (IEP, 2020).

Durante estos días, muchos activistas-diseñadores crearon herramientas y plataformas para hacer las protestas más efectivas, seguras y visibles: páginas de Instagram con colecciones de fotografías y videos de las protestas; guías para la protección digital de activistas; carpetas de Google Drive con ilustraciones para la insurgencia; chatbots de Telegram para apoyar a los manifestantes; y poderosos mensajes que se difundían a través de TikTok, Whatsapp y Facebook invitando a participar en las marchas.

With this piece, my intention is to indicate a possibility on how socio-political struggles question the way design is discussed and practiced today. Additionally, I attempt to reflect on what is the role of designers in such struggles, especially in times when non-violent civil disobedience is necessary for securing democracy. I argue that the tools and initiatives highlighted above can be understood as critical forms of design: placing design as a relevant tool for a socio-political change that is collectively and democratically produced.

The debate of critical scholars on the role of design in the era of globalisation, the Anthropocene, and ubiquitous information technologies argues for rethinking design as a collective process for social innovation (Manzini, 2015) and as a tool for changing our realities, not only in a material sense, but also as the social, ecological, political, and historical formations they are (Escobar, 2018). Moreover, these debates enquire into how design shapes (and is shaped by) power and decision-making processes: who gets to decide what is designed and who gets to use such creations is of tremendous importance. I propose this stance as a relevant lens to learn from the massive protests that recently took place in my country and to open a critical debate on why we should discuss design today.

The circumstances of these protests have been very unusual. Firstly, the country has been enduring a long political crisis since 2016, when groups of conservative corrupt parties managed to win a majority in Congress. During these years, they have created political instability while creeping into different state powers. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has taken the lives of several thousand Peruvians and hit our daily income economy hard. By November, we were still struggling to flatten the curve of the virus spread.

During these harsh circumstances, the Congress’ legislative coup could have been an unstoppable force. Most of the population was already focused on enduring the challenges in their daily lives, which left little room for voicing their rejection to an illegitimate government. Nonetheless, the general reaction was the opposite: citizens started organising massive protests in the streets and daily demonstrations from their homes, taking place in many Peruvian cities and abroad. Due to the pandemic, many supported the protest in events called “cacerolazos”.

These at-home demonstrations consisted of making massive noise by collectively hitting pans from balconies or doorsteps at 8pm every day.

Credit: Alejandro Torero (Author)

En este artículo, mi intención es indicar una posibilidad sobre cómo las luchas sociopolíticas cuestionan la forma en que se discute y se practica el diseño hoy. Asimismo, busco reflexionar sobre cuál es el rol de los diseñadores en estos conflictos. Especialmente, tiempos en los que la protesta civil no violenta es necesaria para asegurar la democracia. Propongo que muchas de las herramientas e iniciativas mostradas arriba pueden entenderse como formas críticas de diseño, al colocarlo como una herramienta relevante para un cambio sociopolítico que se produzca colectiva y democráticamente.

Recientemente, el debate académico crítico sobre el papel que juega el diseño en la era de la globalización, el Antropoceno y las tecnologías de la información plantea entender el diseño un proceso colectivo para la innovación social (Manzini, 2015) y como una herramienta para cambiar nuestras realidades, no solo en un sentido material, sino también como las formaciones sociales, ecológicas, políticas e históricas que son (Escobar, 2018). Aquí propongo este enfoque como una postura relevante para aprender de las protestas masivas que tuvieron lugar recientemente en mi país y para abrir un debate crítico sobre por qué deberíamos discutir el diseño hoy.

Las circunstancias de estas protestas han sido muy inusuales. Primero, el país atravesaba una larga crisis política desde 2016, cuando un grupo de partidos corruptos y conservadores lograron obtener la mayoría en el Congreso. Durante estos años, han creado inestabilidad política mientras se infiltran en diferentes poderes estatales. Además, la pandemia de COVID-19 ha causado la muerte de miles de peruanos y ha afectado duramente nuestra economía que depende de ingresos diarios. Para el mes de noviembre, aún estábamos luchando por aplanar la curva de contagios.

Durante estas duras circunstancias, el golpe legislativo del Congreso pudo haber sido una amenaza imparable. La mayoría de la población estaba enfocada en superar sus dificultades diarias, lo que dejaba poco espacio para expresar rechazo a un gobierno ilegítimo. Sin embargo, la reacción general fue la contraria: la ciudadanía comenzó a organizar protestas masivas en las calles y “cacerolazos” desde los hogares, tanto en muchas ciudades peruanas como en el exterior. Debido a la pandemia, muchos apoyaron las protestas en eventos llamados “cacerolazos”. Estas son protestas realizadas desde los balcones o las puertas de los hogares que consisten en golpear las ollas, sartenes o cacerolas para hacer mucho ruido colectivamente.

Se dieron todos los días a las 8pm.

Credit: Anonymous

Nonetheless, traditional press was initially portraying an undoubtedly biased version of the demonstrations that discredited or diminished the massive unrest. In response, some citizens acted as socio-political designers and created what I call archives of collective action.

These were one of the most important tools during the demonstrations:

ArchivoPE.com

MeroLocoNO.com

No obstante, la prensa tradicional retrataba, inicialmente, una versión indudablemente sesgada de las manifestaciones; desacreditando o disminuyendo el rechazo generalizado. En respuesta, algunos ciudadanos actuaron como diseñadores sociopolíticos y crearon lo que llamaré aquí archivos de acción colectiva. Estas fueron una de las herramientas más importantes durante las demostraciones:

RadioInsurgenica.com

These archives are open digital repositories of pictures, videos, sounds and images of the protests. Citizens were actively recording the current events and spreading them through social media. Archives of collective action were created as open platforms for everyone to watch and to participate by sending or uploading their files. My perception is that the objective of these creations is summed up by the striking phrase:

Estos archivos son repositorios digitales abiertos que contienen fotografías, videos, sonidos e imágenes de las protestas. Los ciudadanos registraron activamente los eventos que ocurrían y los difundieron a través de distintas redes sociales. Se crearon archivos de acción colectiva en Telegram, Instagram, Facebook y páginas web particulares. Y funcionaron como plataformas abiertas que todos pudieran ver y participar enviando sus archivos. Considero que el objetivo de estas creaciones se resume en la llamativa frase:

I argue that these socio-political creations promote designers to rethink our practice. By starting these archives, designers and content creators made use of their knowledge as tools for making insurgency more effective and visible. Undoubtedly, these tools changed the way the demonstrations were coordinated, communicated, and perceived, which also drastically changed their outcome. These collective archives and exchange of evidence rendered it impossible to overlook the reach of the protests and the disproportionately violent police repression.

Moreover, these archives were not created to dictate how the bigger collective was to act. On the contrary, they were placed in the public sphere as a tool to be collectively owned. Finally, the collective could decide and co-create the direction and the content of the archives. This allows us to portray a more democratic form of “history”: one that is not crafted solely by hegemonic powers, but by collective citizenship1. Therefore, the role of designers was to become facilitators and creators of tools that others could use in making more effective and visible their own experiences. To craft an amplifier for the voices of other people2. Instead of defining how people should behave, as normative design frequently does, these situated and socio-political designs have the chance to become truly collaborative and decentralise the role of the individual author in favour of a collective authorship and decentred power structures. Maybe this is what real and deep democracy could be about?

Finally, these protests and their consequences were remarkable and unforgettable. The overwhelming participation and visibility of the protests forced the illegitimate government to resign in less than a week; regrettably, at a high cost. Inti Sotelo and Bryan Pintado, two young men of 24 and 22 years respectively, were killed by the police. Many others were seriously wounded. The violent repression was condemned by national and international organisations and the investigation processes are still open, and they have not assigned guilt yet. Nonetheless, these archives will serve as our collective memories of these events and will likely maintain open space for situating critical design practices as committed tools for socio-political change. Perhaps the first step is that these archives can help in bringing justice to the afflicted families3.

At the time of edition of this article, three more Peruvians were killed by the police in demonstrations against the current agricultural labour law, recently approved by the Congress. The conditions that motivated this article are still open, therefore debates surrounding insurgent struggles need to be taken even more seriously.

1Marisol de la Cadena (2015) also argues for understanding archives as decolonial historical devices.

2As the logo and statements of Insurgencia Radio suggests: https://insurgencia.radio/

3Humans Rights Watch (2020) and IDL-Reporteros (2020) have conducted independent investigations with available material and their results point to possible material and intellectual perpetrators.

References:

de la Cadena, M. (2015) Earth beings: ecologies of practice across Andean worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for the Pluriverse Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Human Rights Watch (2020)

Peru: Serious Police Abuses Against Protesters. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/17/peru-serious-police-abuses-against-protesters (Accessed: 20 December 2020).

IDL-Reporteros (2020) La Muerte de Inti. Available at: https://www.idl-reporteros.pe/la-muerte-de-inti/ (Accessed: 30 November 2020).

[IEP] Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (2020) Informe de Opinión – Noviembre 2020. Available at: https://iep.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Informe-IEP-OP-Noviembre-2020.pdf?fbclid=IwAR397myWtyweBXszD2T9X_HPqtdBCtZ3EtKcmJ5avhjyh-njOBLC1AOe4Ms

(Accessed: 05 December 2020)

Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When Everybody Designs An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Cover Graphics:

Gritaluz; @big.rex1; @nezda_; @ilustracin; @jimenasalinasg; @porhorita; @ruthsoriano

Mi propuesta es que los diseñadores repensemos nuestra práctica a partir de estar creaciones sociopolíticas. Al construir estos archivos, los diseñadores y creadores de contenido utilizaron sus conocimientos como herramientas para hacer más efectiva y visible la insurgencia. Estas herramientas seguramente cambiaron la forma en que se coordinaron, comunicaron y percibieron las manifestaciones. Lo cual también cambió drásticamente su resultado. Estos archivos colectivos y el intercambio de pruebas hicieron imposible pasar por alto la masividad de las protestas y la represión policial desproporcionadamente violenta.

Asimismo, estos archivos no se crearon para determinar cómo debería ser un proceso de acción colectiva hacia una única dirección. Por el contrario, estas plataformas fueron puestas a disposición del público como una herramienta de la que el colectivo se pueda apropiar. Finalmente, fue ese colectivo el que podría decidir y co-crear la dirección y el contenido de los archivos. Esto permite crear una forma más democrática de “historia”: que no es elaborada por poderes hegemónicos, sino colectivamente por la ciudadanía1. Por lo tanto, el papel de los diseñadores fue el de facilitadores y creadores de herramientas que otros pudieran utilizar para hacer más efectivas y visibles sus propias experiencias. Elaboraron una serie de “amplificadores” para las voces de otras personas2. En lugar de definir cómo deben comportarse las personas, como suele hacer el diseño normativo, estos diseños situados y sociopolíticos tienen la posibilidad de volverse verdaderamente colaborativos y descentrar el papel del autor individual en favor de una autoría colectiva y estructuras de poder descentralizadas. ¿Quizás de esto podría tratarse una verdadera y profunda democracia?

Finalmente, estas protestas y sus consecuencias fueron notables e inolvidables. La abrumadora participación y visibilidad de las manifestaciones obligó a que gobierno ilegítimo renuncie en menos de una semana. Lamentablemente, a un costo elevado. Inti Sotelo y Bryan Pintado, jóvenes de 24 y 22 años respectivamente, fueron asesinados por la policía. Muchos otros fueron gravemente heridos. Esta violenta represión ha sido ampliamente condenada por organismos nacionales e internacionales. Los procesos de investigación aún se encuentran abiertos y no se han declarado culpables. Sin embargo, los archivos creados serán nuestra memoria colectiva de las protestas y seguramente abrirán debates para convertir las prácticas de diseño crítico como herramientas comprometidas para el cambio sociopolítico. Quizás el primer paso sea que estos archivos puedan ayudar a llevar justicia a las familias afectadas.

Durante la edición de este artículo, otros tres peruanos fueron asesinados por la policía en manifestaciones contra la actual ley de trabajo agrícola, recientemente aprobada por el Congreso. Las condiciones que motivaron este artículo siguen abiertas. Por lo tanto, los debates en torno a estas luchas insurgentes deben tomarse aún más en serio.

1Marisol de la Cadena (2015) propone entender los archivos como dispositivos históricos decoloniales.

2Como sugiere el logo y mensajes de Insurgencia Radio: https://insurgencia.radio/

Referencias:

de la Cadena, M. (2015) Earth beings: ecologies of practice across Andean worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for the Pluriverse Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

Human Rights Watch (2020) Peru: Serious Police Abuses Against Protesters. Disponible en: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/12/17/peru-serious-police-abuses-against-protesters (Accedido: 20 December 2020).

[IEP] Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (2020) Informe de Opinión – Noviembre 2020. Disponible en: https://iep.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Informe-IEP-OP-Noviembre-2020.pdf?fbclid=IwAR397myWtyweBXszD2T9X_HPqtdBCtZ3EtKcmJ5avhjyh-njOBLC1AOe4Ms (Accedido: 05 December 2020)

IDL-Reporteros (2020) La Muerte de Inti. Disponible en: https://www.idl-reporteros.pe/la-muerte-de-inti/ (Accedido: 30 November 2020)

Manzini, E. (2015)Design, When Everybody Designs An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

author

Alejandro Torero Gamero is a designer-researcher focused on urban and territorial processes. He studied Architecture at PUCP, Peru and holds an MSc in Building and Urban Design in Development from The Bartlett-DPU-UCL, UK.

He is interested in the application of design for improving quality of life and socioecological sustainability. By learning from multiple disciplines and knowledges, he aims to build a transdisciplinary formation and participate in the craft of collective, critical, and holistic projects and processes. His current projects involve working as a Territorial Development Planner for the Peruvian Ministry of Housing while, at the same time, developing a series of independent and academic initiatives in Urban Studies and Critical Design with Peruvian fellows.

first published for projektado magazine issue 0: why discuss design today? / january 2021