‘anonymous’ industrial design and its pursuit in the socialist GDR

Although many contemporary designers acknowledge the importance of sustainability and actively seek to reduce the environmental impact of their products, they often continue to telegraph various identities in consumer product design. This practice tends to increase consumption without a commensurate increase in the satisfaction of needs. At a time of natural resource depletion, environmental destruction and extreme global inequity resulting primarily from global manufacturing activity, these two perspectives seem irreconcilable. The visual expression of identities is rooted in economic conditions and not an inherent aspect of industrial design practice. Designers of the socialist GDR, working under very different conditions, developed a notable design approach in which the articulation of identities had no place. Sharply focused on the resource-efficient satisfaction of needs, they prioritised a product’s practical functionality, longevity and cost-efficient manufacturability and they vigorously rejected all styling. GDR design, consequently, was often perceived as unobtrusive, or even ‘anonymous’, but it had an inclusive appeal and generally withstood the passage of time. This essay considers these different approaches to design through the lens of the ‘anonymity’ of the resulting objects, in order to stimulate more reflection on the impact of identity mediation in and through consumer product design.

When product design is being described as ‘anonymous’, then this is often intended to be interpreted as criticism. During the industrial revolution, observers used this word to express concern about the homogenisation and perceived lack of aesthetic quality of the newly emerging machine-made goods. Later, it resurfaced when design that professed to prioritise practical functionality and avoided decorative detailing was denounced as meaningless and inhumane. This latter instance demonstrates that design does not actually need to be anonymous, i.e. of unknown or unfamiliar origin, in order to be seen as ‘anonymous’: much of the mid-twentieth century canon—the category of products exalted as exemplary by designers and their institutions, although not, it turned out, by the majority of ordinary consumers—consisted of Modernist-inspired ‘anonymous’ design by often well-known designers. [Fig. 1] Conversely, the design of an object can be anonymous, in that we do not know who conceived it, without being experienced as ‘anonymous’, because it contains a myriad of clues about the identity of the object’s manufacturer, the brand it belongs to, the type of user it is aimed at, etc.1 This describes the vast majority of consumer products surrounding us today.

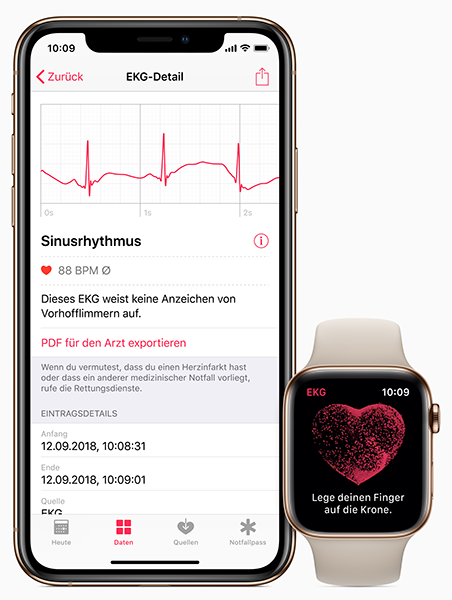

Designers routinely employ multiple practices in the conception and detailing of consumer products to allow these to transport such meanings. For example, the application of a consistent design language across the product range of a manufacturer or brand makes these products easy to identify and connects them to the brand and the values it seeks to represent. [Fig. 2] The observation of contemporary aesthetic trends or styles locates the origin of a product firmly within a particular discourse at a particular moment in time. Even the more random visual details often applied to consumer products in order to differentiate them from competitors in saturated markets tend to reflect notions about their intended users and can also come to assume new meanings while in circulation, allowing consumers to use these products to send messages about themselves to each other.

All of this signalling, however, comes at a price. It leads to increased consumption. Users are enticed to purchase products just to buy into the lifestyle promised by a brand or to consume them conspicuously to send certain messages to the people around them. Objects are discarded and replaced because they evoke trends that are no longer current or because some of their connotations have changed. This type of additional consumption, although often considered desirable by businesses and by some economists, seems incompatible with simultaneous efforts to address some of the major challenges were are facing, including natural resource depletion, environmental pollution and climate change, but also the extreme social and economic inequity we continue to see throughout the world.

The visual expression of identities in the design of consumer products is not an inherent aspect of industrial or product design practice. It became a custom only in response to market economic conditions and a certain degree of affluence among consumers. It did not, therefore, feature in the work of industrial designers in the now-defunct socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR), who operated under very different conditions.2 Here manufacturers were not focused on maximising profits or market share, but on fulfilling production quotas assigned to them by economic planners seeking to organise the satisfaction of the population’s needs. Unlike in the West, consumption was not seen as an engine of economic growth. In fact, since the GDR lacked significant indigenous supplies of raw materials and was thus beset by persistent shortages, great care was taken not to arouse additional needs beyond those already in existence.

Under these circumstances, and undoubtedly influenced by practitioners who had been connected to the Modern Movement and especially the Bauhaus before World War 2, GDR designers adopted a functionalist design approach which was rooted in the underlying aim to meet the needs of the people as efficiently as possible. This principle informed their writings as well as their practical work, where it led to the routine prioritisation of functionality, efficient manufacturability and longevity. Significantly, the GDR designers’ understanding of a product’s function included, in addition to the more obvious utilitarian and operational functions (i.e. practical purpose and usability), an aesthetic function. Yet, their simultaneous pursuit of high volume mass production and long product lifespans precluded them from seeking beauty in the application of any extraneous features or detailing, which might have had only limited or temporary appeal. They were particularly averse to passing trends or ostentatious decoration. ‘Streamlined furniture and coffee pots are as absurd as lion claws on a writing desk’, proclaimed Horst Michel, one of the founding fathers of GDR design in 1956.3 Instead GDR designers sought a more objective visual appeal in the choices they made about a product’s overall form and the treatment of its functionally and technologically determined features, with which they pursued aesthetic qualities that were deemed to appeal more reliably and universally to all human beings, such as visual clarity or balance.

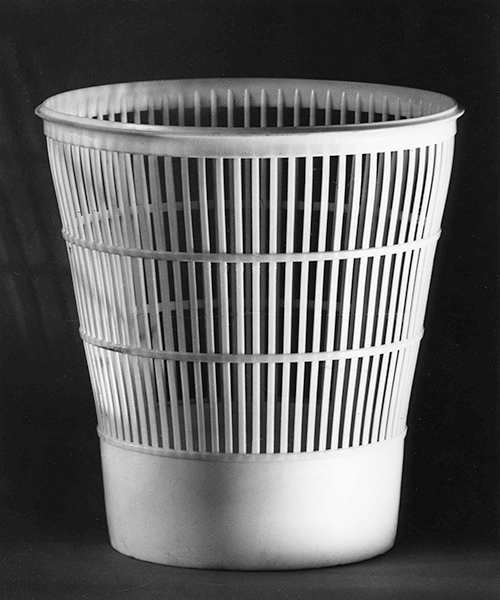

This perspective and the resulting design approach led to consumer products that were overwhelmingly characterised by harmonious restraint.4 [Fig. 3, 4] They typically consisted of simple, well proportioned forms with functional and technical elements, such as controls, handles, ventilation slots, mounting screws or joint lines, that were positioned in carefully considered relationships to each other. The absence of more extraneous detailing in these objects obstructed their interpretation and the absorption of additional meanings. They were perceived as ‘anonymous’—or ‘cold, clean, meaningless’, as observed by an incensed ideologue of the ruling SED party in his appeal for design that better expressed society’s zest for socialism.5 [Fig. 5] On the other hand, the ‘anonymity’ of these objects ensured that they were bought and used for what they were, rather than for something else they might have represented, and that they could enjoy long lifespans in both use and production because they did not go out of style. Many of the consumer products originally designed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when industrial design first took off in the GDR, remained in popular demand and continued to be produced up until, and in some cases beyond, the state’s demise in 1990. [Fig. 6, 7]

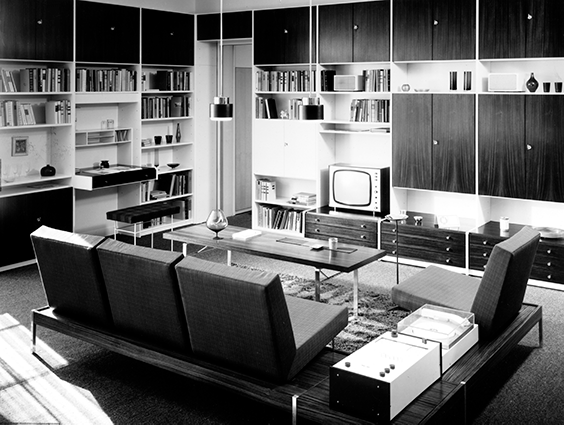

‘Anonymous’ design also did not spell an end to individuality. GDR designers recognised a significant opportunity in the design of modular product systems: Such systems could provide the users with a selection of standardised, visually restrained components, which the users could then combine themselves to create relatively unique solutions that fulfilled their own personal needs. ’The appropriation of products thus becomes an active, critical and creative process, rather than one of passive enjoyment’, wrote the industrial designer Ekkehard Bartsch.6 This idea was exemplified by MDW, a popular furniture system designed in 1966/67 by a team led by Rudolf Horn, also a vocal advocate of ‘active consumption’, and manufactured by the VEB Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau. [Fig. 8] MDW was conceived as a pool of coordinated components that could be assembled by the user, according to their specific requirements, to construct a diverse range of furniture for virtually all areas of the home. The formal restraint of its individual components allowed MDW to fit harmoniously into a wide variety of environments, prevented it from going out of style and afforded the user a degree of self-expression not normally associated with the consumption of mass produced objects. This kind of thinking was also applied to more complex technical consumer goods.

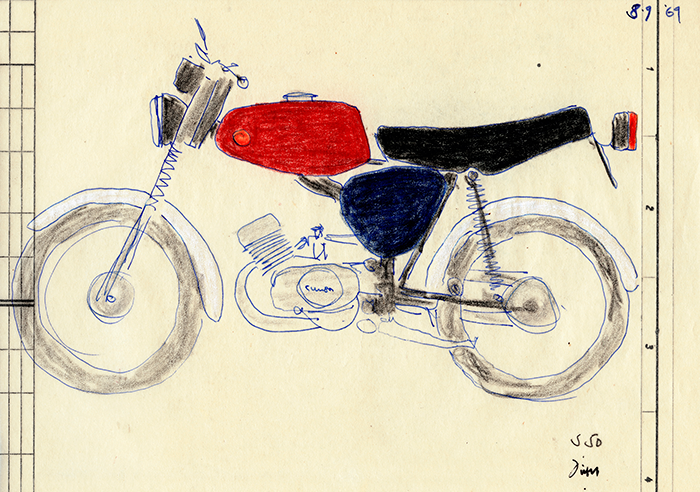

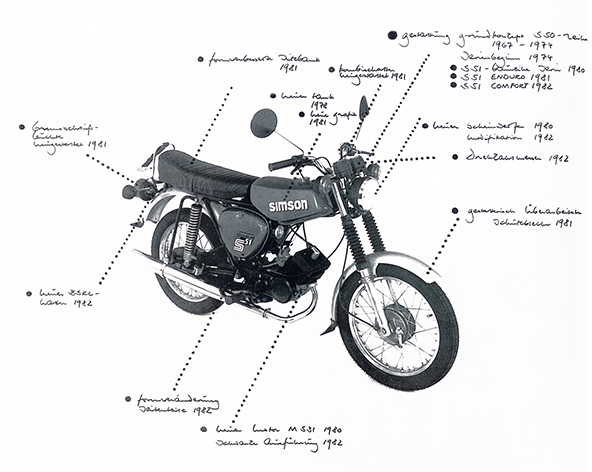

Throughout the latter 1960s and the 1970s, the industrial designers Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph tested and advocated their ‘open principle’, a construction method that sought to assemble a product’s various components or subassemblies in such a way that they could be easily replaced with alternative or updated versions. This allowed not only for customisation, and thereby self-expression and satisfaction of differentiated user needs, but also for repairs and upgrades, and thereby longer lifespans in use and production. The most successful implementation of the ‘open principle’ can be found in the Mokick S50, a small low-powered motorcycle designed in 1967 by Dietel and Rudolph in collaboration with engineers of the VEB Fahrzeug- und Gerätewerk Suhl. [Fig. 9] Constructed of freely accessible and formally independent subassemblies, the bike was able to be continuously improved and updated by its manufacturer—as well as its users, who could retrofit new parts into their existing bikes—for almost twenty years. [Fig. 10] It went out of production shortly after the GDR’s collapse, but individualised versions of the S50 continue to be used, maintained and modified to this day.

This suggests that ‘anonymous’ design may be better suited to fulfilling the needs of the user, and indeed those of mankind more generally, than the alternative approaches we are more familiar with in consumer cultures today. Rather than something to be feared or denigrated, ‘anonymous’ design might play a crucial role in efforts to induce more respect from the user for the object itself, for its inherent usefulness, for the labour and materials that have gone into making it, thus supplanting an attitude that values objects primarily as vehicles for the transmission of quite peripheral ideas and information. Such efforts are not envisaged to replace other sustainable design strategies—the use of low-impact materials or renewable energy sources, for example, or design for repair, disassembly, recycling or reuse—which typically aim to reduce a product’s environmental footprint over the various stages of its lifecycle. Instead, such efforts to change consumer attitudes would boost the impact of these established methods by fostering stronger and more lasting bonds between the users and their objects and thereby slowing down the entire product lifecycle itself. By contrast, the seemingly innocuous practice of styling tends to undermine their impact by speeding up product lifecycles, as shown above. Of course, for many of today’s industrial designers such a change in working practices is no straightforward proposition. They would need to find ways of asserting themselves first against the consumer culture system within which they are operating. But they might be able to rise to this challenge. Awareness is the first step.

Fig. 1 Photosuper SK4 phonograph and radio, designed by Hans Gugelot and Dieter Rams, 1956, manufactured by Braun AG

Photo: Braun Archiv / Copyright Braun P&G

Fig. 2

iPhone, originally designed by Jony Ive & team, 2007, and Apple Watch, originally designed by Jony Ive, Kevin Lynch & team, 2017, developed and marketed by Apple Inc.

Photo: Apple Inc.

Fig. 3

Heliradio modular series: RK3 (tuner) + P1 (record player) + L20 (speaker), designed by Karl Clauss Dietel and Lutz Rudolph, 1963-65, manufactured by Gerätebau Hempel KG Limbach-Oberfrohna Photo: Günter Höhne

Fig. 4

Stern-Dynamic portable radio, designed by Dietmar Palloks and Michael Stender, 1971, manufactured by VEB Kombinat Stern-Radio Berlin until 1981

Photo: Katharina Pfützner

Fig. 5

Cylindrical vases, designed by Hubert Petras, 1961, manufactured by VEB Porzellanwerk Lichte-Wallendorf and among the objects explicitly singled out for public criticism

Photo: Klaus Götz; R. Luckner-Bien (ed.), Hubert Petras Design: Eigene Arbeiten und Arbeiten der Schüler (Halle, 1995)

Fig. 6

Vessels for baking and cooking, designed by Ilse Decho, 1962, manufactured by VEB Schott & Gen. Jena until at least 1979

Photo: Erich Müller

Fig. 7

Waste basket in polyethylene, designed by Albert Krause, 1960, manufactured by VEB Preßwerk Ottendorf, Ottendorf-Okrilla until at least 1986

Photo: Walter Danz; Sammlung Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle

Fig. 8

MDW modular furniture system, designed by Rudolf Horn & team, 1967, manufactured by VEB Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau (in variants) until 1991

Photo: Friedrich Weimer; Hochschularchiv Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle

Fig. 9

Mokick S50 motorbike, designed by Karl Clauss Dietel, Lutz Rudolph & team, 1967, manufactured by VEB Fahrzeug- und Jagdwaffenwerk ‘Ernst Thälmann’ Suhl until 1991 (from 1980 with a new motor as S51) Sketch: Karl Clauss Dietel, 1969

Fig. 10

Mokick S50 motorbike, designed by Karl Clauss Dietel, Lutz Rudolph & team, 1967, manufactured by VEB Fahrzeug- und Jagdwaffenwerk ‘Ernst Thälmann’ Suhl until 1991 (from 1980 with a new motor as S51) Graphic (illustrating model updates): Karl Clauss Dietel, 1982

footnotes

1/ The designers of these products are not truly anonymous in that their identities can be established, but they are not generally well known beyond their professional circles and they play no role in the product’s promotion, unlike Philippe Starck and Michael Graves did, for example, when they designed for Alessi.

2/ See Katharina Pfützner, Designing for Socialist Need: Industrial Design Practice in the German Democratic Republic, London and New York: Routledge, 2018.

3/ Horst Michel, ‘Das Angemessene’, Bildende Kunst, 11/12 (1956), pp. 652-655, here p. 652. All translations are by this author.

4/ It should be noted here that this did not describe GDR material culture more generally, as in the GDR—similar to most other countries—industrial designers only had a limited impact on what was produced as a whole.

5/ Karl-Heinz Hagen, ‘Hinter dem Leben zurück: Bemerkungen zur “Industriellen Formgestaltung” auf der V.Deutschen Kunstausstellung’, Neues Deutschland, 4 October 1962, p. 4. For clarity should be added here that GDR design, like most Western design, was also anonymous in the more commonly used sense of the word, in that the identity of its designers, though generally credited and recognised for their work within professional circles, was not known to its typical consumers.

6/ Ekkehard Bartsch, ‘Standardisierung — Vielfalt — Formgestaltung’, Form und Zweck, No. 2 (1965), pp. 7-12, here p. 11.

author

Katharina Pfützner is Lecturer in Industrial Design at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin, Ireland. She has a background in design consultancy and an interest in various aspects of design theory and practice, particularly in socially responsible design strategies. She also holds a PhD in design history and has been researching and writing about industrial design in the GDR. Her book Designing for Socialist Need: Industrial Design Practice in the German Democratic Republic (Routledge) was published in 2017. She is a member of the Institute of Designers in Ireland, the Design History Society and the Gesellschaft für Designgeschichte.

first published for projektado magazine issue 1: anonymity in design / may 2021