There is a complex relation between surveillance and anonymity. Surveillance functions as a way to strip privacy layer by layer until a naked self is revealed to observing eyes, removing any privacy. Not only does it expose actions, but thoughts, feelings and social relations are observed and archived through a variety of invasive means. Simultaneously, it dehumanizes the observed, rendering complex individuals as mere points of anonymous data. It can be used in secret to accumulate compromising information, or openly, to induce paranoia among rivals. State actors understand how increasing surveillance is directly related to their power, and proportionally invest in tools of surveillance on different fields. As such, surveillance isn’t neutral, since political agendas guide which groups and individuals are being observed. Surveillance by the state is not limited to their own frontiers, as espionage, extrajudicial detentions and assassinations are continually carried out by state actors in foreign territories. In order to analyze this phenomenon, the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), colloquially known as drones, will be used as a lens to explore the degrees to which surveillance, anonymity and identity have been shifted by the use of these tools by powerful military structures in the context of the War on Terror.

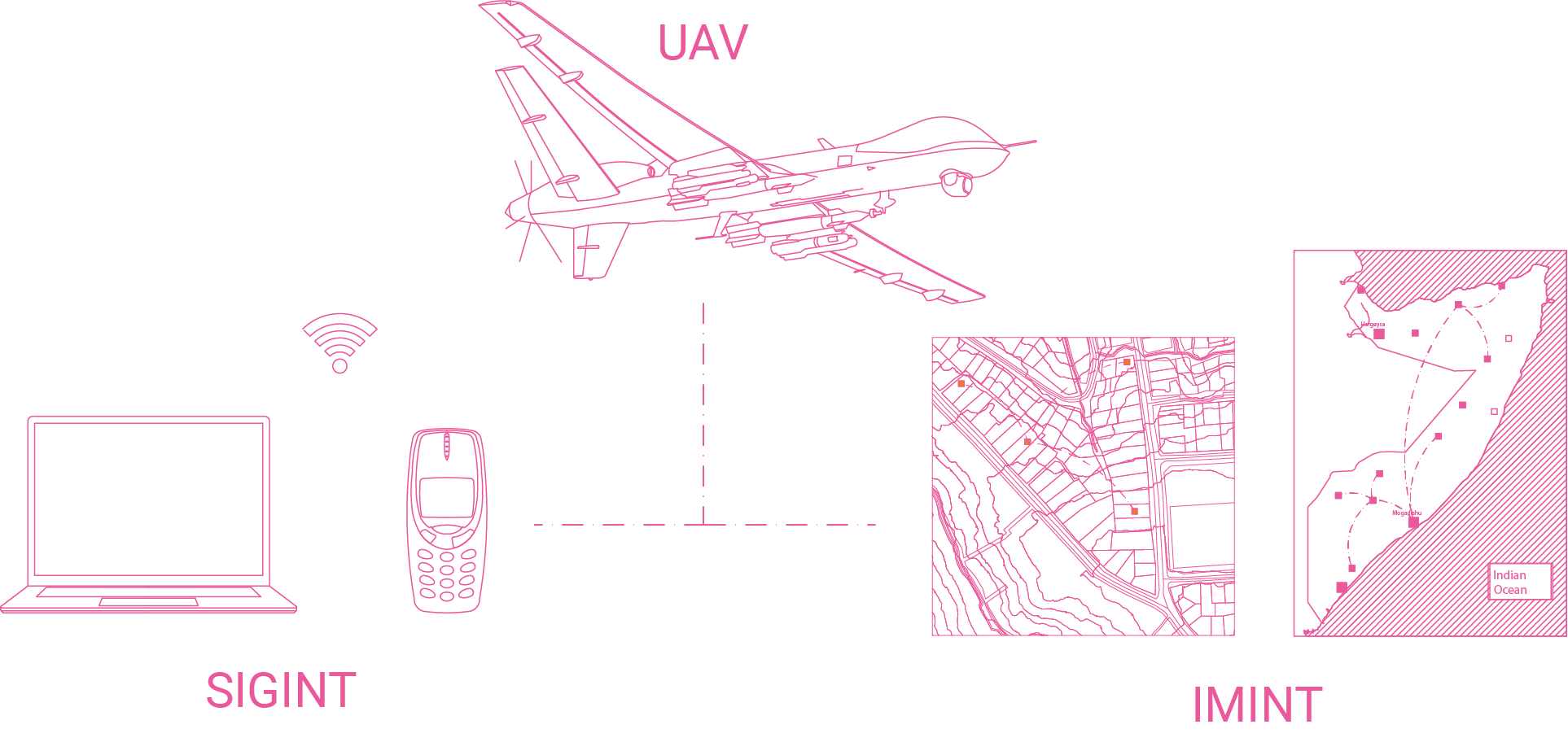

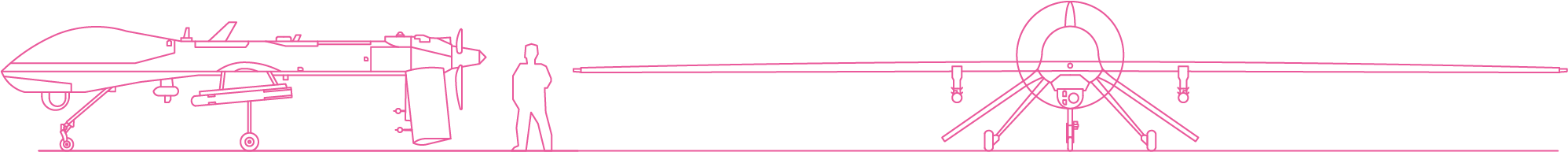

UAVs have been extensively developed during the last two decades in order to conduct both surveillance and military operations without risking the lives of military personnel becoming one of the most relevant technological advancements of the War on Terror. This article will draw on the effects of the extended use of UAVs as surveillance and war equipment by NATO-affiliated countries in both declared war zones, such as Iraq and Afghanistan, and undeclared war zones, such as Somalia and Yemen. The nature of this distinction is considered significant as different tactics and resources have been dedicated to these different territories, and in the case of undeclared war zones, intelligence is recovered almost exclusively through the use of UAVs through image intelligence such as aerial photography (IMINT) and signal intelligence such as electronic communications (SIGINT)1. This information is accumulated, analyzed and may be used as proof to carry out targeted assassinations against individuals deemed hostile against the interest of NATO countries. UAVs have greatly expanded the capacity of military organizations to operate freely and unchallenged as they give enemy combatants little means to evade them other than dropping off the grid altogether.

As a tool for surveillance, drones operate on a basic concept: Permanence of sight. They allow intelligence agencies and militaries to continuously stalk targets on territories where little to no manpower has been deployed on the ground, thus greatly reducing the risk for their personnel and furthering the perception of how wars can be carried “in a clean manner”. The current-day use of UAVs for surveillance has expanded the capacity of state powers to a level of omniscience, or at least that’s what they’d like to pretend. But in reality, surveillance is full of ‘blinks’, gaps in vigilance when targets cannot be observed directly. Regarding the use of UAVs in conflict zones, these blinks occur mainly by what military authorities denominate “the tyranny of distance”, referring to the limited flight capacities of drones when measured from their airfields, particularly in undeclared war zones that do not present enough infrastructure to sustain continuous operations2. Stemming from this is the argument that insists that the persistent stare cannot be achieved unless the infrastructure of surveillance is expanded, which results in more military bases being built with this objective all over the Global South. This creates a vicious circle which more tools are required to conduct more surveillance, justifying an increase in investment in military infrastructure to provide results, which, as it will be explored later, also results in more civilian deaths.

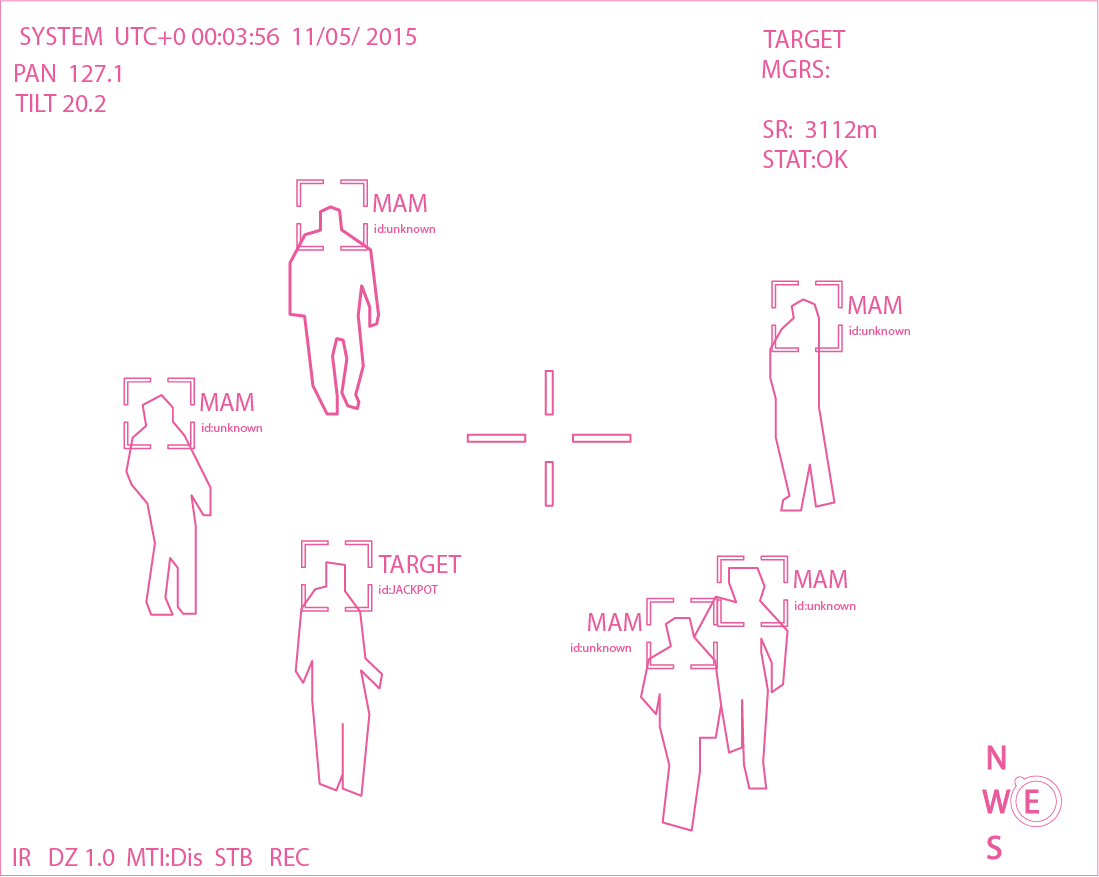

While SIGINT and IMINT may seem like solid sources of intelligence, they create an overreliance on certain selectors to monitor presenting a partial or distorted portrait of the activities of intended targets. Usually, the approach taken to this information is of “trust, but don’t verify” as it is assumed that if enough elements of someone’s digital footprint are suspicious, no further confirmation may be required, which may lead to fatal errors. The espionage of SIM cards, for example, is particularly susceptible to create faulty intelligence through misinterpretation, as a phone may be shared among several individuals or simply not belong to the intended target. More precise profiles may be developed through human intelligence (HUMINT) but contacting informants requires on-ground personnel, and relying on local intelligence agencies has in the past led to faulty information acquired by dubious methods or guided by local conflicts and struggles for power. Patterns of conduct have been modeled that rely exclusively on SIGINT and IMINT sources to detect suspicious activity, which has led to the execution of “signature strikes”, or assassinations against unidentified individuals based solely on the accumulation of suspicious behavior3. This tendency to strip targets of their identity and read them as merely a summation of data points is a weaponization of anonymity, dehumanizing the target to the point where the morality of killing a human being is not brought up since “the data justifies the action”.

In addition to collecting intelligence, drones provide intelligence agencies with “instantaneity of solutions”, the capacity to swiftly apply lethal force in short windows of time against perceived enemies by severely lowering the threshold required for its use. In order to make effective use of the time constraints contained within operational protocols, the definition of “imminent threat” becomes instrumental. Since this is by and large the only criteria needed to approve an operation, the imminence of this threat does not specifically require targets to be actively planning a specific hostile action, as they are considered targetable 24/7 regardless of whether they are actually participating in violent activities at any given point. This is particularly egregious in cases when targets are entitled to due process in accordance to their citizenship. In order to accelerate the execution of targeting assassinations, shortcuts are being applied. For instance, the removal of citizenship of UK nationals deemed enemies was used as they would be otherwise required to be arrested by their country of nationality and receive trial to determine their role in possible terrorist threats instead of being summarily executed as foreigh enemy combatants4. The removal of citizen rights can be seen as bureaucratic dehumanization, literally stripping rights away from individuals in order to speed up their elimination5. The immediacy of death provided by the tools of war has only sped up these actions.

Even considering an operational point of view, assassinations are, at best, an intelligence dead end. Killing intended targets has a twofold negative effect when fighting against enemy combatants: First, in the case where the victim was indeed a threat, it eliminates any possible HUMINT that might have been collected through other means of incapacitation such as an arrest. Assassination does not provide future leads to be exploited or new information to be analized. Second, and more importantly, the high incidence of civilian casualties incurred by drone operations when compared to other modes of warfare can be tied to an increase in the antagonism of local populaces towards occupying foreign forces, thus extending the permanence of conflict as new generations face the trauma of constantly being on the receiving end of unexpected acts of violence. This in particular has been hidden under the military term of “precision striking”, a deliberately ambiguous concept which has misled the public into believing UAV strikes as being highly accurate, precisely hitting the intended target and nothing else. In reality, “precision striking” within a military context refers specifically to the accumulation of assets to enable a strike to take place6. This disguised the reality of drone strikes under the guise of a clean war, hiding the real human trauma it causes.

the mechanical application of trauma

The mixture of a desire for expediency, faulty intelligence and a general disregard for lives of those inhabiting the Global South has caused severe consequences within societies where UAVs have been deployed as tools of war. Reports indicate that during Operation Haymaker, conducted in the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan from 2011 to 2013 by the US Military, the succesful assassination of 35 targets was accompanied by the death of over 200 casualties7. The unintended victims cannot be accurately described as accidental civilian casualties since all reports produced after the operation denominate them as “enemies killed in action” even if no official information has been given by involved parties to justify this classification. The lack of transparency over the nature of these actions obfuscates the cruel human costs caused by the use of these tools. For example, the concept of MAM (military age male) is used to identify young males as enemy combatants even if no information exists on their activities. Whenever an unidentified MAM is killed as an unintended target of some kinetic action, their guilt is assumed by mere physical proximity to the event. Their own anonymity is weaponized to justify their category as an enemy. Thus, a defining aspect of the use of UAVs as weapons of war is an absolute lack of accountability over extrajudicial killings, as no responsible parties can be identified to acknowledge their involvement and face the consequences of killing civilians. In particular, undeclared war zones such as Somalia present critical gaps in intelligence as resources and manpower in the area are comparatively low in respect to Afghanistan or Iraq, which very often leads to faulty targeting. As a direct consequence, “mistakes” are considered acceptable and the killing of those living in these territories is, at best, assumed as an inevitable aspect of the use of UAVs in the War on Terror.

UAVs are not autonomous machines, they require flight teams to maintain and operate the drones both in their respective airfields and within their nation of origin. The need for constant vigilance of intended targets requires UAV pilots to engage with them on a constant, if covert, basis. This permanent vigilance forces pilots to observe individuals not just as they allegedly engage in hostile activities, but also as they go on through their daily lives. Pilots have reported how this creates a sense of intimacy with their surveillance objectives, which may eventually develop into empathy8. Because of this, it has been reported that PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) levels among UAV pilots are similar to those of servicemen who have engaged in active combat. On the other hand, civilians living under the constant threat of bombing by drones have also developed increased levels of PTSD. Yemeni civilians, already living under vulnerable conditions, see the open sky as a source of trauma9. Both operators and civilians carry a toll by the use of drones, but so far, only the psychological cost paid by pilots has been addressed since, unlike the suffering in foreign territories, this trauma may hinder the future of UAV programs. The psychological damage of pilots is addressed by the military through the removal of the capacity for empathy by streamlining the chain of decision making into a diffuse network of responsibility, not necessarily out of concern for the pilots’ wellbeing but as a means to streamline operations even further. But the trauma of the killer pales in comparison to that of those living under deadly skies. The trauma of the victims lies at the intersection of the immediacy of an unexpected death and the complicit knowledge that an unknowable someone, somewhere, pulled that trigger.

Along the evident trauma caused by the unexpected death of a loved one, the lack of a logical explanation to understand the randomness of this death inflicts a particular strong kind of psychological damage within the families of victims, as no possible measures can be rationally taken to avoid facing the same fate. Unlike accidents or disease, having the knowledge that this death was not the result of fate but was a deliberate action perpetuates victimhood, grief and fear. Simultaneously, the material impact of death within impoverished communities fuels further victimization, as widows and orphans are usually the ones left destitute whenever a drone kills a random civilian. Within this, it would be a mistake to declare civilian casualties as the mere product of human error conducted by drone operators themselves, instead of an actual policy that renders them as acceptable and dismissable.

Culturally, NATO forces have faced the trauma caused by war through the suffering of its soldiers, young men and women having their lives destroyed by conflict in far away lands. The mythology surrounding veterans is accompanied by media depictions of suffering snipers and flags folded over rows of caskets. The political cost of the War on Terror is measured in western lives and named deaths. Drones, more than anything else, offer the political conductors of these wars the possibility to remove this cost from the equation under the knowledge that trauma caused to those living overseas is considered irrelevant within their cultural boundaries10. As long as the killed are foreigners in distant territories, the War on Terror could potentially carry on indefinitely. Only during the peculiar occasions when a civilian death gets counted, such as the unintended killings of the American and Italian hostages, Warren Weinstein and Giovanni Lo Porto, does the western public get a reminder of the actual imprecision that routinely plagues drone operations.

Advanced Force Operations have turned the whole world into a battlefield. Not just as a potential scenario, but as a dangerous frontier that is under endless surveillance by a military machinery designed to preventively destroy potential threats before they become actual enemies. The use of UAVs has created a conflict scenario in which the use of lethal force against dubious targets has been encouraged while death is imparted with absolute immunity under the guise of security11. The dehumanization of victims is built into the bureaucracy of their use, as surveillance renders humans as mere points of anonymous data, flattening relations to justify the continuous use of violence. As long as this dehumanization of the Global South keeps going, widespread death will continue to be an unavoidable result.

designed for violence

The 2013 film Kaze Tachinu (The Wind Rises), directed by Hayao Miyazaki, tells a fictionalized biography of Japanese aircraft designer Jiro Horikoshi, the mind behind the flight aircrafts Mitsubishi A5M and A6M Zero, which were used by the Imperial Japanese Air Army Service during WWII. The movie explores what is the role and social responsibility of one who designs instruments of war. Throughout the narrative, Horikoshi is depicted as someone who is simply enamored with planes, a beautiful and romantic object of design that exists outside the realm of morality. But as we have seen, these tools don’t exist in a moral vacuum of pure engineering wonder, and may in fact be catalysts for the facilitation of conflict and war. Are the efforts of Horikoshi merely “captured” by an imperial project, his marvelous inventions corrupted by his context? Or should the designers of war machines be subjected to moral criticism and self-reflection regarding the possible end results of their designs?

As we have seen with UAVs, the presence of these machines in conflict zones has severely increased the willingness and expediency by which lethal force is deployed towards innocent civilians. The process by which such wondrous designs come into existing requires the dedicated effort of hundreds of professionals, all of them perfecting their capacities for flight autonomy, target detection, etc. It must be clarified however that there is a difference between designing a tool that could potentially be used for war and an outright weapon, as UAVs may prove to be a very useful technology in other fields of human endeavor. But we have seen how their deployment in conflict zones has severely increased the amount of trauma and death suffered in the Global South, a direct consequence of an expedience by design. As with the case of Horikoshi, the role of professionals involved in the development of these machines does not exist outside of the realm of accountability. As designers and engineers, we have a moral responsibility regarding the final use of our inventions, as neither ignorance nor disinterest may justify our role in perpetuating suffering.

footnotes

1/ Scahill, J. (2015) The Assassination Complex, The Drone Papers, The Intercept [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at

https://theintercept.com/drone-papers/the-assassination-complex/

2 / Currier, C. & Maass, P. (2015) Firing Blind, The Drone Papers, The Intercept [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at https://theintercept.com/drone-papers/firing-blind/

3 / Currier, C. (2015) The Kill Chain, The Drone Papers, The Intercept [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at https://theintercept.com/drone-papers/the-kill-chain/

4/ Woods, C. & Ross, A. (2013) Former British citizens killed by drone strikes after passports revoked, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2013-02-27/former-british-citizens-killed-by-dron e-strikes-after-passports-revoked

5/ The Economist (2012) A very British execution? [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at https://www.economist.com/baobab/2012/01/25/a-very-british-execution

6/ Long, J. (2012)The Problem with “Precision: Managing Expectations for Air Power, MA thesis, United States Army War College

7/ Devereaux, R. (2015) Manhunting in the Hindu Kush, The Drone Papers, The Intercept [Online, accessed on 16-03-2021] Available at

https://theintercept.com/drone-papers/manhunting-in-the-hindu-kush/

8/ Sapolsky, R. (2017) Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, Penguin Press, London

9/ Nemar, R. (2017) Psychological Impact, The Humanitarian Impact of Drones, Women’s International League for Peace & Freedom, Disarmament Institute, Pace University, New York

10/ Igoe Walsh, J. & Schulzke, M. (2015) The Ethics of Drone Strikes: Does Reducing The Cost of Conflict Encourage War? US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute

11/ Cole, C. (2017) Harm to Global Peace and Security, The Humanitarian Impact of Drones, Women’s International League for Peace & Freedom, Disarmament Institute, Pace University, New York

author

Fernando is a Chilean urban practitioner and researcher, specialised in urban informalities, disaster risk reduction in cities and participatory urban design. He works as an architect in informal communities. He holds a MSc. in Building and Urban Design in Development from the Bartlett’s Development Planning Unit (UCL) and he is a licensed architect from the University of Valparaíso (Chile). He has lived in Chile and the UK.

first published for projektado magazine issue 1: anonymity in design / may 2021